[[Dear Sr Laurel, Several people you have responded to have been rejected by their dioceses for admission to vows and consecration as a diocesan hermit. One of the things that is very clear is how difficult such a decision is for them. One of the things I have appreciated in your posts is that although you point out the differences between lay hermits and canonically professed hermits, or between consecration of self (dedication of self) and consecration by God mediated by the Church, you do really seem to esteem these vocations similarly. Another thing that has struck me is how little help the Church actually offers in assisting people to come to terms with such a rejection. My impression is once a diocese (or Order) says "no" to a person in this way that's all the contact there is. Am I wrong in this? Also, if a diocese says no, is the person free to come back and request another hearing or is the door closed forever? Are dioceses honest in all of this? Charitable?]]

[[Dear Sr Laurel, Several people you have responded to have been rejected by their dioceses for admission to vows and consecration as a diocesan hermit. One of the things that is very clear is how difficult such a decision is for them. One of the things I have appreciated in your posts is that although you point out the differences between lay hermits and canonically professed hermits, or between consecration of self (dedication of self) and consecration by God mediated by the Church, you do really seem to esteem these vocations similarly. Another thing that has struck me is how little help the Church actually offers in assisting people to come to terms with such a rejection. My impression is once a diocese (or Order) says "no" to a person in this way that's all the contact there is. Am I wrong in this? Also, if a diocese says no, is the person free to come back and request another hearing or is the door closed forever? Are dioceses honest in all of this? Charitable?]]

Thanks for your comments and questions. I am gratified that you have recognized one of the reasons I have written a lot about all this and answered questions which had already been asked a number of times. I know sometimes it can be really tiring to do this and likely it is tiresome to readers as well. Still, in light of Vatican II --- a Council that is still being received by the Church --- the laity's call to an exhaustive holiness has been made exceedingly clear. The challenge is to get folks to truly understand that and internalize the sense that the lay vocation, whether eremitical or not, is precious to God and to the Church. It is not an entrance level vocation nor is it less worthy of esteem than other vocations in the Church.

I believe that much of what was written at Vatican II was designed to counter the notion of higher and lower vocations. We still have a long way to go in this and in truly understanding what Thomas Aquinas was referring to when he spoke of the "objective superiority" of a particular vocation or state of life. Moreover, to the extent that Aquinas' mindset was actually incompatible with the upside-down values of Jesus' Kingdom teaching, we still have some ways to go to distance ourselves from that mindset as well. The simple fact is this. Vatican II recognized that ALL are called to an exhaustive holiness; there is no hierarchy involved in this. Paul meanwhile recognized that ALL are significant members of Christ's body, differently as each function. But each is essential to the functioning of the others. Imagine a person who can see, but is unable to speak of what she sees, or who is unable to analyze what she sees or act on what she analyzes. The eyes need the mouth and the brain; the hands and legs need the others as well. Nothing can be done in isolation and no member is unimportant.

I believe that much of what was written at Vatican II was designed to counter the notion of higher and lower vocations. We still have a long way to go in this and in truly understanding what Thomas Aquinas was referring to when he spoke of the "objective superiority" of a particular vocation or state of life. Moreover, to the extent that Aquinas' mindset was actually incompatible with the upside-down values of Jesus' Kingdom teaching, we still have some ways to go to distance ourselves from that mindset as well. The simple fact is this. Vatican II recognized that ALL are called to an exhaustive holiness; there is no hierarchy involved in this. Paul meanwhile recognized that ALL are significant members of Christ's body, differently as each function. But each is essential to the functioning of the others. Imagine a person who can see, but is unable to speak of what she sees, or who is unable to analyze what she sees or act on what she analyzes. The eyes need the mouth and the brain; the hands and legs need the others as well. Nothing can be done in isolation and no member is unimportant.

You are generally correct that when a diocesan chancery staff person says no to admission to profession as a consecrated hermit, for instance, there is little further contact between the petitioner and the diocese per se. The task of coming to terms with a rejection of this sort is something one is generally expected to work out with one's usual support system. This would mean one's friends, family, spiritual director (especially!), perhaps one's pastor, et al. Discernment does not cease with the diocese's decision but instead enters into a more intense or demanding period. In some cases dioceses will essentially say to a person, "We do not believe you are suited to this vocation and will not profess you in this. We do not believe this is a matter of time alone." In such a case it would take a significant change in one's life to change this discernment or even to get a serious hearing which might reopen or begin another discernment process.

You are generally correct that when a diocesan chancery staff person says no to admission to profession as a consecrated hermit, for instance, there is little further contact between the petitioner and the diocese per se. The task of coming to terms with a rejection of this sort is something one is generally expected to work out with one's usual support system. This would mean one's friends, family, spiritual director (especially!), perhaps one's pastor, et al. Discernment does not cease with the diocese's decision but instead enters into a more intense or demanding period. In some cases dioceses will essentially say to a person, "We do not believe you are suited to this vocation and will not profess you in this. We do not believe this is a matter of time alone." In such a case it would take a significant change in one's life to change this discernment or even to get a serious hearing which might reopen or begin another discernment process.

But sometimes the diocese says instead, "Go off and live in solitude for a time." What may also be either implied (more likely) or stated explicitly (less likely) is, "When you have actually done that for at least a couple of years, and if you still feel you are called to consecration as a diocesan hermit then make an appointment with the Vicar For Religious or the Director of Vocations and we will look at the possibility once again." Both of these answers are entirely honest and create a way forward for the one still discerning. Decisions are made on a case by case basis so whether the door is closed or will open again in the future depends on many things. It really is up to the person discerning to deal with the diocese's own discernment and decisions and to find the forms of support s/he can to move on with integrity. I think in the main dioceses are honest in their discernment and charitable in the way they deal with candidates and former candidates.

Moreover, unless the diocese says they have determined one is unsuited to this vocation (and this is likely to have specific grounds), most folks always have the right to come back at another time and try again --- that's especially so when a diocese simply has refused to profess anyone at all under canon 603 or has refused to identify one so professed as a diocesan hermit. (My own diocese once called such a person a "diocesan Sister," but not a diocesan hermit; they then decided they were not going to use canon 603 for the foreseeable future. At that point I had worked with the Vicar for Religious for five years and we were both anticipating my admission to profession. The Bishop's decision surprised us both and left my own discernment at a new and painful place.) Later I renewed my petition, and was, in time, perpetually professed as a diocesan hermit in 2007. (However, I lived as a hermit through the intervening years, reflected on canon 603, on the alternative lay hermit vocation, and determined I needed to approach the diocese once again. My sense today is that the Diocese of Oakland is glad I am professed as a Catholic Hermit in their jurisdiction and that I persevered in petitioning the diocese to mutually discern this vocation.

Moreover, unless the diocese says they have determined one is unsuited to this vocation (and this is likely to have specific grounds), most folks always have the right to come back at another time and try again --- that's especially so when a diocese simply has refused to profess anyone at all under canon 603 or has refused to identify one so professed as a diocesan hermit. (My own diocese once called such a person a "diocesan Sister," but not a diocesan hermit; they then decided they were not going to use canon 603 for the foreseeable future. At that point I had worked with the Vicar for Religious for five years and we were both anticipating my admission to profession. The Bishop's decision surprised us both and left my own discernment at a new and painful place.) Later I renewed my petition, and was, in time, perpetually professed as a diocesan hermit in 2007. (However, I lived as a hermit through the intervening years, reflected on canon 603, on the alternative lay hermit vocation, and determined I needed to approach the diocese once again. My sense today is that the Diocese of Oakland is glad I am professed as a Catholic Hermit in their jurisdiction and that I persevered in petitioning the diocese to mutually discern this vocation.

The bottom line is that most dioceses will reconsider earlier decisions, especially if there is a truly experienced and suitable candidate. While the waiting period in my own situation was unnecessarily prolonged, at the same time it was an important period of growth. None of that is lost in my life today. Each day something more from the solitude I experienced and the discernment process I engaged in becomes freshly fruitful. Eremitical life is always more about the journey than the destination so what I am saying is that my journey would have been meaningful no matter whether I was ever admitted to perpetual profession and consecration under canon 603 or not.

Any hermit has to trust this truth about the solitary journey with and in God because it is really not easy to get a diocese to accept one for profession under canon 603 --- nor should it be! After all, a diocese has to have the sense that this truth about the journey's importance is true of this candidate! One has to demonstrate over the long haul the ability to live the solitary life on one's own initiative. One must establish links and meaningful relationships with parishes; they must get education and training, establish regular spiritual direction, find work suitable for an authentic hermit living the silence of solitude, and determine how one will keep oneself throughout one's life --- all while living an exemplary eremitical life --- even if profession and consecration is apparently not in one's future. This can all take time but it is my sense that when one has done this a diocese is apt to listen to where one has come to from the time of their initial rejection or temporizing decision in this person's regard.

03 July 2015

On Dealing With Dioceses and With Rejection in Regard to Canon 603

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:49 PM

![]()

![]()

02 July 2015

Hermits, The Antithesis of the Rugged Individualist or the One Who is a Law unto Herself!

[[Dear Sister, I have two different questions. 1) You once wrote a piece about hermits, canon law, and herding cats. I remember you both agreed and disagreed with the person who said legislating for hermits was impossible and like herding cats. Recently you said in another piece that hermits were like fingerprints, each unique but with recognizable patterns, whorls, loops, etc. I know you think highly of canon 603 but I wondered if you thought it was sufficient to legislate the life of solitary hermits. Does there need to be canon law on the formation of hermits, on time frames prior to profession and final profession? 2) Also, why do you see individualism as so completely antithetical to eremitical life? Aren't hermits the consummate individualists? If each is an 'ecclesiola' as Peter Damian (and you too) say, then doesn't this make each hermit a kind of law to him or herself?]]

[[Dear Sister, I have two different questions. 1) You once wrote a piece about hermits, canon law, and herding cats. I remember you both agreed and disagreed with the person who said legislating for hermits was impossible and like herding cats. Recently you said in another piece that hermits were like fingerprints, each unique but with recognizable patterns, whorls, loops, etc. I know you think highly of canon 603 but I wondered if you thought it was sufficient to legislate the life of solitary hermits. Does there need to be canon law on the formation of hermits, on time frames prior to profession and final profession? 2) Also, why do you see individualism as so completely antithetical to eremitical life? Aren't hermits the consummate individualists? If each is an 'ecclesiola' as Peter Damian (and you too) say, then doesn't this make each hermit a kind of law to him or herself?]]

Is Canon 603 Sufficient to Govern and Nurture Solitary Eremitical Life?

First of all I do believe canon 603 is sufficient, generally speaking. I think there need to be some guidelines about formation, time frames, minimum ages and experience required for admission to discernment and profession, as well as regarding the distinction between being a lone individual and being a hermit in some essential sense, and also some significant cautions on what canon 603 is NOT meant for. However, at this point in time I don't see any reason these things would need to be codified in canon law or through an actual papal motu proprio for instance.

Bishops and Vicars for Religious need to be able to discern with each candidate while doing justice to the flexibility of canon 603 and the diversity which is part of the history of eremitical life itself, but they also need additional help understanding the Church's desert tradition and the very challenging history of this canon so that not just anything is called eremitism. Especially they must recognize that not just any form of aloneness is called "eremitical solitude" nor can just any form of living and working alone be called eremitical life. The misuse of canon 603 as a stopgap to profess individuals who wish to be religious while merely desiring or needing to live alone is a significant problem that must be avoided. The vocation must be a truly eremitical one. At this point it seems sufficient that in addition to the canon and the expertise of canonists and theologians (especially ecclesiologists), hermits contribute their own experience in these matters and dioceses do the same. One of the reasons for this blog as well as for something like the Network of Diocesan Hermits is to allow for this kind of reflection in a way which is available to anyone looking for assistance in implementing canon 603.

Solitary Hermits and Individualism:

Some critics of this blog have been very critical of diocesan hermits providing insights from their own living and reflecting on canon 603, the life it governs and nurtures, and therefore, their reflection on the kinds of life it absolutely should not be mistaken for. Whenever I have fielded questions or objections or even quotations from these folks I have the sense that they are most upset by my position that not just anything goes, not just anything can be called eremitical life in line with the Church's own understanding and eremitical tradition. Canon 603 is not meant to profess those who simply could not be professed any other way (though there will be a handful who could not be professed in community and who discover a genuine call to eremitical life). It is not meant to govern a nominally pious life without meaningful theological education and formation in spirituality --- especially in desert spirituality. Neither is it meant for those who want to live some silence and some solitude (even significant amounts of these) or desire mainly to separate themselves from others or from the post-conciliar Church, but who do not really hunger to live a LIFE of the silence of solitude.

Some critics of this blog have been very critical of diocesan hermits providing insights from their own living and reflecting on canon 603, the life it governs and nurtures, and therefore, their reflection on the kinds of life it absolutely should not be mistaken for. Whenever I have fielded questions or objections or even quotations from these folks I have the sense that they are most upset by my position that not just anything goes, not just anything can be called eremitical life in line with the Church's own understanding and eremitical tradition. Canon 603 is not meant to profess those who simply could not be professed any other way (though there will be a handful who could not be professed in community and who discover a genuine call to eremitical life). It is not meant to govern a nominally pious life without meaningful theological education and formation in spirituality --- especially in desert spirituality. Neither is it meant for those who want to live some silence and some solitude (even significant amounts of these) or desire mainly to separate themselves from others or from the post-conciliar Church, but who do not really hunger to live a LIFE of the silence of solitude.

It is the notion that "the silence of solitude" is the charism of the diocesan hermit, the gift the Holy Spirit creates in her life and the gift she herself brings to the Church and world that might help me answer your questions about individualism. A lot of people think of a hermit's work as praying for people and while I agree that is an important piece of our lives, I don't think it is the main work we do. Rather, our main work is to allow God to work in us, that is to become God's own prayer --- a prayer that witnesses to the fact that the grace of God is truly sufficient for us and God's power is made all-embracing (i.e., is perfected) in weakness. There is nothing individualistic in this. Instead there is a real dying to self so that one might be fully transparent to God, fully human in God, and witness to all of this so that others might also allow themselves to become who and what they were made to be in God. The hermit is a person in communion; they live in communion with God, with themselves, and in the heart of the Church for the sake of others. There is no room for individualism nor selfishness here.

Like a local Church the hermit is an ecclesiola, a little Church. But this means she represents the whole and is intimately related to the larger Church, first every other ecclesiola (Christian person), then the parish, then the diocesan Church, and then finally the universal Church. Each person, but especially the hermit is a microcosm of what it means to be called, to live the response in a way which is always transparent to the God who calls, and to do so for the sake of others. The hermit lives a life in which she is free to plumb the depths of communion with God. She is free to be herself in the fullest way possible in an intense and all-encompassing relatedness. She is not, however free to do just anything she wants. That is not freedom after all; it is license and it is similarly the hallmark of individualism. Thus I say the eremitical vocation is actually antithetical to individualism. To represent the Church (as any Christian is ecclesiola) and to live this vocation in the name of the Church is to be a person-in-relationship more than it is to be an individual in some senses of that term.

Like a local Church the hermit is an ecclesiola, a little Church. But this means she represents the whole and is intimately related to the larger Church, first every other ecclesiola (Christian person), then the parish, then the diocesan Church, and then finally the universal Church. Each person, but especially the hermit is a microcosm of what it means to be called, to live the response in a way which is always transparent to the God who calls, and to do so for the sake of others. The hermit lives a life in which she is free to plumb the depths of communion with God. She is free to be herself in the fullest way possible in an intense and all-encompassing relatedness. She is not, however free to do just anything she wants. That is not freedom after all; it is license and it is similarly the hallmark of individualism. Thus I say the eremitical vocation is actually antithetical to individualism. To represent the Church (as any Christian is ecclesiola) and to live this vocation in the name of the Church is to be a person-in-relationship more than it is to be an individual in some senses of that term.

Hermits, A Law Unto Themselves?

The canon 603 hermit is never a law unto him or herself. Her life is given over to the will of God and to the law which that God writes on her heart. She lives a life whose parameters are defined by Canon and proper law (Rule or Plan of Life) as well as by the living eremitical tradition of the Church. It is a life nurtured by the Sacraments, fed by the Word of God and lived under the various forms of supervision of Bishop, delegate, spiritual director, and pastor as well as by an oblate chaplain or other similar figure in cases of oblature or associateship with an institute of consecrated life. She is vowed to God through profession of the evangelical counsels and thus she is bound to obedience to God in the hands of a legitimate superior; she is bound, in other words, both morally and in law. The "hermit" who is not so bound (and who thus mistakes license for genuine freedom) has been a perennial thorn in the side of eremitical leaders and reformers throughout the history of the Church. St Benedict castigated these, St Peter Damian did likewise as did Paul Giustiniani and many many others.

Certainly the notion of hermit as rugged individualist and law to him or herself is common as a stereotype. A few years ago I blogged about a journalist's t stupid identification (sorry but it's true!) of Tom Leppard and one other person as living classic and somehow edifying lives of eremitical solitude. I would suggest you check out those posts with labels like "stereotypes," "Tom Leppard," etc. In contemporary theology (Paul Tillich, 20 C.) we would recognize the autonomous person as antithetical to the theonomous person; that is, we would find the person who was a law unto herself as antithetical to the one who has God as her law (that is, the Lord and driving dynamic of her heart). The hermit is almost a pure paradigm of theonomous life. Certainly this alone is what s/he aspires to and represents when s/he says that by her life s/he witnesses to the fact that God alone is sufficient or that in God we are called and fulfilled as human beings who live for one another. And isn't this also the definition of Church, namely the community of the called who find their fulfillment and missionary purpose in the God of Love who is both their nomos (law) and telos (goal)?

Certainly the notion of hermit as rugged individualist and law to him or herself is common as a stereotype. A few years ago I blogged about a journalist's t stupid identification (sorry but it's true!) of Tom Leppard and one other person as living classic and somehow edifying lives of eremitical solitude. I would suggest you check out those posts with labels like "stereotypes," "Tom Leppard," etc. In contemporary theology (Paul Tillich, 20 C.) we would recognize the autonomous person as antithetical to the theonomous person; that is, we would find the person who was a law unto herself as antithetical to the one who has God as her law (that is, the Lord and driving dynamic of her heart). The hermit is almost a pure paradigm of theonomous life. Certainly this alone is what s/he aspires to and represents when s/he says that by her life s/he witnesses to the fact that God alone is sufficient or that in God we are called and fulfilled as human beings who live for one another. And isn't this also the definition of Church, namely the community of the called who find their fulfillment and missionary purpose in the God of Love who is both their nomos (law) and telos (goal)?

I sincerely hope this is helpful. Your questions are important ones and ones I am keenly interested in so thanks for those!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:24 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: individualism and narcissism, Paul Tillich, solitude vs isolation, stereotypes, Theonomy vs Autonomy, Tom Leppard, Validation vs redemption of Isolation

26 June 2015

Private Dedication: The Significance of the Lay Eremitical Vocation (Once Again)

[[Hi Sister, I am trying to live as a hermit and am discerning whether to go to my Bishop and ask him to profess me as a diocesan hermit. I have consecrated my life to Christ and I believe he has consecrated me to himself as well. I celebrated this with my spiritual director who is a priest and the ceremony we used was really lovely. I think you wrote that consecrations are not supposed to be piled on top of each other. If that is so then is it necessary to go to the Bishop to become a consecrated hermit? Can't he simply recognize that?]]

Hi there yourself and thanks for your questions. I don't remember saying that consecrations are not meant to be piled on top of one another. I once wrote that Bishops in France had determined that the consecration of virgins and that of hermits were not meant to be added to one another, that each of these was complete in themselves. Neither, then, were they to be substituted for one another. Perhaps this is what you are remembering. This was because early on some hermits were offered the consecration of virgins before their dioceses were ready to allow the consecration of diocesan hermits. Later the eremitical consecration was sometimes done when the diocese was ready to consecrate hermits. Instead the character of each vocation should have been discerned and appropriately celebrated by the diocese.

Similarly, the addition of one consecration to the other has sometimes happened in occasional dioceses when a consecrated hermit might desire to add the consecration of virgins because of the nuptial quality of her relationship with Christ. My sense is it is really not meaningful or consistent with the eremitical vocation because the rite of consecration of virgins for women living in the world (canon 604) signifies a form of consecrated or sacred secularity. Secularity, sacred or otherwise, is actually incompatible with the hermit calling which is explicitly marked by stricter separation from the world. (The use of the consecration of virgins which is celebrated after solemn profession of cloistered nuns, and might be proposed for usage after solemn profession and the consecration of hermits seems to me --- and seemed to the French Bishops --- to be equally unnecessary.)

Your own question is an interesting one. You have had an experience of Christ sanctifying you in a way which fits you for particular mission. It was and is for you a signifcant experience which you may not or even probably do not desire to "diminish" by adding other kinds of dedications or consecrations. The difficulty here is that this was a private experience; it was not mediated by the Church (this requires a Bishop or someone acting for him with the specific intention of consecrating you in the name of the Church) and therefore, does not represent the mediation of a public ecclesial vocation in the Church. It was undoubtedly a remarkable experience which I hope you will esteem for the rest of your life, but it did not function as an ecclesial profession and consecration under canon 603 functions nor can it therefore be used to substitute for these.

Your own question is an interesting one. You have had an experience of Christ sanctifying you in a way which fits you for particular mission. It was and is for you a signifcant experience which you may not or even probably do not desire to "diminish" by adding other kinds of dedications or consecrations. The difficulty here is that this was a private experience; it was not mediated by the Church (this requires a Bishop or someone acting for him with the specific intention of consecrating you in the name of the Church) and therefore, does not represent the mediation of a public ecclesial vocation in the Church. It was undoubtedly a remarkable experience which I hope you will esteem for the rest of your life, but it did not function as an ecclesial profession and consecration under canon 603 functions nor can it therefore be used to substitute for these.

In other words, your Bishop cannot merely recognize this experience in order to make you a diocesan hermit. That requires a mutual discernment, followed by ecclesial mediation of the call, response (profession), and consecration. Or again, it requires a canonical or juridical act on the part of the Church which initiates you into the consecrated state of life, a state of life marked by specific graces, as well as canonical rights and obligations. These are taken on and extended to the person in the rite of profession and consecration. They cannot be given in any other way. You see, something happens to the person in these acts. These acts are language events, specifically, they are performative language events where one embraces the rights and obligations in the very act of profession. (A judge's verdict or an umpire's call are also examples of performative language as are vows of all sorts.) The Church calls the person forward, symbolically examines her on her readiness to accept these specific rights and obligations, prays the litany of the Saints over (and with) her as she lays prostrate and prepares to give her entire life to be made a consecrated person and eremite, and then admits her to profession (by definition a public human act) and consecration (by definition a mediated divine act) where she takes on a new and public state of consecrated life.

If you should decide you wish to (seek to) be consecrated as a diocesan hermit with a public ecclesial vocation, there is no way such an act will diminish the sanctifying experience you have already had or the dedication you have already made. It will specify it (and more importantly, specify the consecration of your baptism) in significant ways; it will also change your status in law and grace to that of the consecrated state, but the experience you describe will be integrated into the hermit you eventually become and may stand at the very heart of your identity. With God nothing is ever lost.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:57 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: consecrated v dedicated hermits, importance of lay eremitical vocations, public vs private vows

25 June 2015

A Few Thoughts on Custody of the Eyes

[[Hello Sister Laurel, Thank you for putting up the piece about the new movie. Custody of the eyes is not a phrase we hear much about today. When I looked it up I found a reference to "10 reasons men should always practice custody of the eyes" and some forum posts talking about avoiding lust, but why would cloistered nuns be practicing custody of the eyes so much to name a film about it? I mean is it really that central to life in a cloister? What am I missing?]]

[[Hello Sister Laurel, Thank you for putting up the piece about the new movie. Custody of the eyes is not a phrase we hear much about today. When I looked it up I found a reference to "10 reasons men should always practice custody of the eyes" and some forum posts talking about avoiding lust, but why would cloistered nuns be practicing custody of the eyes so much to name a film about it? I mean is it really that central to life in a cloister? What am I missing?]]

Hi there and thanks for the questions. I agree that custody of the eyes is kind of an old-fashioned term and not one we use or, for that matter, practice much today, but in a congregation such as the Poor Clares or the Trappistines, for instance, it is a significant value which has a good deal less to do with avoiding lustful feelings and more with protecting the privacy, and more, the silence of solitude of one's Sisters and of the house more generally. Interestingly, custody of the eyes is meant to be combined with a genuine sensitivity to the needs of one's Sisters (or others more generally); for instance, one is expected to be aware if someone needs something at table and offer it, or to do something similar in work situations with tools and materials being used, so custody of the eyes does not mean closing oneself off to others, cultivating general unawareness, isolation, or anything similar. I think custody understood in this more balanced way is one of those values we ought all to cultivate as appropriate to our own states of life. It seems to me in some ways it is a vital practice our own technological and media-driven world really needs.

In last Friday's Gospel lection we heard the Matthean observation that the eye is the lamp of the body. In Matthew a good eye is a generous one; a bad or evil eye is the opposite. Additionally, one of the meanings of Matt's observation is that what we look on changes us and can be a source of light or (increasing) darkness. This can occur in many ways. We read classic works of literature or contemporary books that enlighten and shape us. We do the same with art and media of all sorts. Unfortunately, this may involve "literature" which demeans the human person, or it may involve visual input that does not even pretend to be art --- and rightly so. More commonly for most of us, it involves commercials or TV programs which objectify us, make a parody of and trivialize our lives even as they presume to tell us who we are, what we desire, and need, what we ought to value, buy, otherwise spend resources on, and so forth. Custody of the eyes in this kind of thing means allowing God to shape us and show us who we are and what we really need. It means refusing to allow others to define us or our own hearts especially. Custody of the eyes is a necessary element in being our (and God's!) own persons.

In last Friday's Gospel lection we heard the Matthean observation that the eye is the lamp of the body. In Matthew a good eye is a generous one; a bad or evil eye is the opposite. Additionally, one of the meanings of Matt's observation is that what we look on changes us and can be a source of light or (increasing) darkness. This can occur in many ways. We read classic works of literature or contemporary books that enlighten and shape us. We do the same with art and media of all sorts. Unfortunately, this may involve "literature" which demeans the human person, or it may involve visual input that does not even pretend to be art --- and rightly so. More commonly for most of us, it involves commercials or TV programs which objectify us, make a parody of and trivialize our lives even as they presume to tell us who we are, what we desire, and need, what we ought to value, buy, otherwise spend resources on, and so forth. Custody of the eyes in this kind of thing means allowing God to shape us and show us who we are and what we really need. It means refusing to allow others to define us or our own hearts especially. Custody of the eyes is a necessary element in being our (and God's!) own persons.

On the other hand, what we look on, that is, what we choose to look on and the way in which we do so speaks about our hearts; that is, it reflects either the light or the darknesses of our own hearts. Here is where generosity or its opposite become critical. We see this when we look on another person and judge them on the basis of appearances, or otherwise jump to conclusions on the basis of past hurts; but we also see it when we allow our compassion to perceive a person as God's own precious one who is really very like us, when we look with awe at the beauty which surrounds us or find beauty in the simplest thing rather than with the vision of someone who is bored and jaded and incapable of being truly surprised, and so forth. Custody of the eyes has as much to do with truly allowing the eyes to be the lamp of the whole person as with simply avoiding lust or lasciviousness.

On the other hand, what we look on, that is, what we choose to look on and the way in which we do so speaks about our hearts; that is, it reflects either the light or the darknesses of our own hearts. Here is where generosity or its opposite become critical. We see this when we look on another person and judge them on the basis of appearances, or otherwise jump to conclusions on the basis of past hurts; but we also see it when we allow our compassion to perceive a person as God's own precious one who is really very like us, when we look with awe at the beauty which surrounds us or find beauty in the simplest thing rather than with the vision of someone who is bored and jaded and incapable of being truly surprised, and so forth. Custody of the eyes has as much to do with truly allowing the eyes to be the lamp of the whole person as with simply avoiding lust or lasciviousness.

Custody of the eyes allows a person to attend to their own hearts without constantly being distracted by the activity and sights around them. Especially, as it does this, it assists us in becoming people who see things truly, that is, who see things as God sees them. Moreover, it provides space and the gift of privacy for others with whom one lives; especially it provides for the communion we call "the silence of solitude" in which they too are seeking to dwell so that they too may be persons who see as God sees. Custody of the eyes intends our living with focus; it fosters the containment and denial of the incessant voice of curiosity and even prurience that has been intensified with the computer and social media environment and assists in following through on a project without getting distracted. (N.B., even the monastic cowl or cuculla ("hood") helps us maintain custody of the eyes and appropriate focus.) Thus, I think, the practice of custody of the eyes is rooted in a true reverence for others and for ourselves even as it helps create an environment where others may experience the same.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:23 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Custody of the Eyes, media and the eremitical life, silence of solitude, Stricter separation from the world

23 June 2015

A Contemplative Moment: On Simplicity

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:15 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A Contemplative Moment, Letting go Letting God, Simplicity

21 June 2015

Chosen, Custody of the Eyes

There have been times I and other diocesan hermits have been criticized by readers for having blogs, for making our public professions at parish Masses instead of in smaller unattended venues, for allowing others to see pictures of us or our hermitages, for identifying ourselves with titles or post-nomial initials, and so forth. The criticisms have sometimes been leveled that we are not sufficiently humble or respectful of the Catechism description of our lives as hidden. I have argued that this is a public vocation with public rights and obligations, among which are witnessing to the Gospel of Jesus Christ in our solitary hiddenness. In so doing I have pointed out the tension that thus exists in living an essentially hidden life which is contemplative, rooted in stricter separation from the world, and also has a significant public (in the canonical sense of the word) and prophetic dimension.

There have been times I and other diocesan hermits have been criticized by readers for having blogs, for making our public professions at parish Masses instead of in smaller unattended venues, for allowing others to see pictures of us or our hermitages, for identifying ourselves with titles or post-nomial initials, and so forth. The criticisms have sometimes been leveled that we are not sufficiently humble or respectful of the Catechism description of our lives as hidden. I have argued that this is a public vocation with public rights and obligations, among which are witnessing to the Gospel of Jesus Christ in our solitary hiddenness. In so doing I have pointed out the tension that thus exists in living an essentially hidden life which is contemplative, rooted in stricter separation from the world, and also has a significant public (in the canonical sense of the word) and prophetic dimension.

There is a new film being made about the Poor Clare Colletines of Corpus Christi Monastery in Rockford, Illinois. The film, comprised of a series of video reflections made by a novice discerning the life, is entitled, Chosen, Custody of the Eyes and though I recommend folks consider checking out and contributing to the project (more about that below) it was the short clip included below from Mother Abbess which most struck me. Here Mother explains why the Poor Clare Colletines agreed to participate in this project. She speaks very precisely of living a public vocation in the Church though in a hidden life! Although Mother does not explicitly say this is one of the ways the Holy spirit is at work in the Church which requires witness in the midst of one's hiddenness. I believe it is implicit in the whole of this brief clip.

Similarly, I very much appreciated the distinction

Mother draws between a project which is "about us" (and thus,

prohibited) and one which is about their life itself, the life they live in the

name of the Church. The distinction is not absolute --- one needs to be

seen and heard to some extent in order to point beyond oneself to the life

itself --- but this is indeed the aim, viz, to be known and heard only

for the sake of the vocation, the life itself, and especially for the sake of the God who is

glorified in our lives. That is true of this film and I believe it is similarly true of this

blog. Thus, I am gratified on a number of levels that Mother consented

to the making of this film and most especially to speaking

directly about the "whys" of this decision.

Folks interested in funding this film should check out the following link: Chosen, Custody of the Eyes. There are some great perks being offered as incentives for very reasonable contributions indeed (I am going to contribute myself)!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:46 PM

![]()

![]()

20 June 2015

On Laudato Si: When an Encyclical is REALLY an Encyclical!

Well, Pope Francis' new encyclical, Laudato Si (from the first line, "Praise be to you, my Lord" has been out just one day and already it is the talk of the world. Those who ordered copies from the USCCB or Amazon have not even received theirs yet, but the encyclical is up on the Vatican website and can be copied and printed or read right there. Apparently many are doing just that. Though I am sure most reporters and politicians have not had time to read the letter yet --- many are depending on what their colleagues have gleaned and are quoting and requoting Francis' observation that the world is becoming a huge pile of filth --- there is a clear sense of dismay in some arenas that Francis "did not stick to religion". Others of us are excited by the integrated vision Francis provides of a sacramental world and his unflinching reiteration of the call to do justice as we hear and respond to both "the cry of the world and the cry of the poor." This is authentic religion at its best!

Well, Pope Francis' new encyclical, Laudato Si (from the first line, "Praise be to you, my Lord" has been out just one day and already it is the talk of the world. Those who ordered copies from the USCCB or Amazon have not even received theirs yet, but the encyclical is up on the Vatican website and can be copied and printed or read right there. Apparently many are doing just that. Though I am sure most reporters and politicians have not had time to read the letter yet --- many are depending on what their colleagues have gleaned and are quoting and requoting Francis' observation that the world is becoming a huge pile of filth --- there is a clear sense of dismay in some arenas that Francis "did not stick to religion". Others of us are excited by the integrated vision Francis provides of a sacramental world and his unflinching reiteration of the call to do justice as we hear and respond to both "the cry of the world and the cry of the poor." This is authentic religion at its best!

How often does it happen that people wait with bated breath for the publication of a new book? We saw it happen with the Harry Potter series. There bookstores were open at midnight on the release day and lines were out the door and around the corner. Then folks holed up for the next day or two reading and began sharing with everyone what Rowling had done with the characters the plot, etc. I suppose it has happened with the newest romance novel by certain authors --- though I admit I really am not sure. It has happened with movies, some from the Star Wars or Star Trek series, for instance. And in a similar way it has happened with this encyclical. Imagine people virtually standing in line waiting for the Vatican to publish the letter to hear what Francis has to say on matters of the environment! Imagine them calling one another up, walking into daily Mass, emailing, etc and saying, "Wow, Francis has really done it! You HAVE to read this encyclical!" or, "Hey, what about that Francis?!" And yet, that is precisely what happened yesterday morning, what is happening now, what is true of Laudato Si!

How often does it happen that people wait with bated breath for the publication of a new book? We saw it happen with the Harry Potter series. There bookstores were open at midnight on the release day and lines were out the door and around the corner. Then folks holed up for the next day or two reading and began sharing with everyone what Rowling had done with the characters the plot, etc. I suppose it has happened with the newest romance novel by certain authors --- though I admit I really am not sure. It has happened with movies, some from the Star Wars or Star Trek series, for instance. And in a similar way it has happened with this encyclical. Imagine people virtually standing in line waiting for the Vatican to publish the letter to hear what Francis has to say on matters of the environment! Imagine them calling one another up, walking into daily Mass, emailing, etc and saying, "Wow, Francis has really done it! You HAVE to read this encyclical!" or, "Hey, what about that Francis?!" And yet, that is precisely what happened yesterday morning, what is happening now, what is true of Laudato Si!

This is truly an encyclical in the original sense of that term --- a letter that suggests the papacy is profoundly relevant to our own lives and the life of our world, that affirms that what the Office of Peter offers our world is a vision of reality, a vision of possibility we must embrace if we do not desire to see the destruction of that world, a wholistic perspective in which faith and reason, politics and social justice, the Creation narratives and theology of the Old Testament, the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the analyses of the sciences inform and enrich one another. It is a letter that will be read and handed on and read again and quoted, grappled with, argued over, reflected on and prayed with, a letter people will be inspired and motivated by. In other words, it is an encyclical which is truly a Papal encyclical representing a faith which is truly catholic in every sense of that term.

This is truly an encyclical in the original sense of that term --- a letter that suggests the papacy is profoundly relevant to our own lives and the life of our world, that affirms that what the Office of Peter offers our world is a vision of reality, a vision of possibility we must embrace if we do not desire to see the destruction of that world, a wholistic perspective in which faith and reason, politics and social justice, the Creation narratives and theology of the Old Testament, the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the analyses of the sciences inform and enrich one another. It is a letter that will be read and handed on and read again and quoted, grappled with, argued over, reflected on and prayed with, a letter people will be inspired and motivated by. In other words, it is an encyclical which is truly a Papal encyclical representing a faith which is truly catholic in every sense of that term. Is this part of the so-called, "Francis effect"? Is it a sign of a genuine "new" Pentecost; something that --- instead of the gehenna-like fires of ecological and social destruction kindled and fed by the drive for unbridled power, or linked to greed, selfishness, carelessness and outright indifference --- can set the world on fire with a love that does justice for all of God's creation? Then thanks be to God! Laudato Si mi Signore!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

8:48 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Creation, Divine Justice, ecology, Francis, Laudato Si, love that does justice, Papal encyclicals, Pope Francis, Social Justice

18 June 2015

Feast of St Romuald, Camaldolese Founder (Reprised)

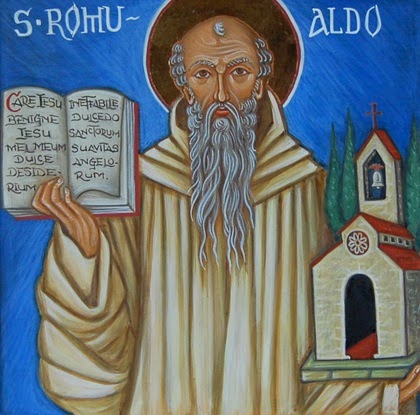

| Romuald Receives the Gift of Tears, Br Emmaus O'Herlihy, OSB (Glenstal) |

Congratulations to all Camaldolese and Prayers! Tomorrow, June 19th is the the feast day of the founder of the Camaldolese Congregations! We remember the anniversary of solemn profession of many Camaldolese as well as the birthday of the Prior of New Camaldoli, Dom Cyprian Consiglio.

Ego Vobis, Vos Mihi,: "I am yours, you are mine"

Saint Romuald has a special place in my heart for two reasons. First he went around Italy bringing isolated hermits together or at least under the Rule of Benedict --- something I found personally to resonate with my own need to seek canonical standing and to subsume my personal Rule of Life under a larger, more profound, and living tradition or Rule; secondly, he gave us a form of eremitical life which is uniquely suited to the diocesan hermit. St Romuald's unique gift (charism) to the church involved what is called a "threefold good", that is, the blending of the solitary and communal forms of monastic life (the eremitical and the cenobitical), along with the third good of evangelization or witness -- which literally meant (and means) spending one's life for others in the power and proclamation of the Gospel.

| Stillsong Hermitage |

Theirs is a rich heritage, unique in the Church. This particular form of life makes provision for the deep human need for solitude as well as for the life shared alongside others in pursuit of a noble purpose. But because their life is ordered to a threefold good, the discipline of solitude and the rigors of community living are in no sense isolationist or self-serving. Rather both of these goods are intended to widen the heart in service of the third good: The Camaldolese bears witness to the superabundance of God's love as the self, others, and every living creature are brought into fuller communion in the one love.

|

| Monte Corona Camaldolese |

In any case, the Benedictine Camaldolese charism and way of life seems to me to be particularly well-suited to the vocation of the diocesan hermit since she is called to live for God alone, but in a way which ALSO specifically calls her to give her life in love and generous service to others, particularly her parish and diocese. While this service and gift of self ordinarily takes the form of solitary prayer which witnesses to the foundational relationship with God we each and all of us share, it may also involve other, though limited, ministry within the parish including limited hospitality --- or even the outreach of a hermit from her hermitage through the vehicle of a blog!

In my experience the Camaldolese accent in my life supports and encourages the fact that even as a hermit (or maybe especially as a hermit!) a diocesan hermit is an integral part of her parish community and is loved and nourished by them just as she loves and nourishes them! As Prior General Bernardino Cozarini, OSB Cam, once described the Holy Hermitage in Tuscany (the house from which all Camaldolese originate in one way and another), "It is a small place. But it opens up to a universal space." Certainly this is true of all Camaldolese houses and it is true of Stillsong Hermitage as a diocesan hermitage as well.

The Privilege of Love

For

those wishing to read about the Camaldolese there is a really fine

collection of essays on Camaldolese Benedictine Spirituality which was

noted above. It is written by OSB Camaldolese monks, nuns and oblates. It

is entitled aptly enough, The Privilege of Love and includes

topics such as, "Koinonia: The Privilege of Love", "Golden Solitude,"

"Psychological Investigations and Implications for Living Alone

Together," "An Image of the Praying Church: Camaldolese Liturgical

Spirituality," "A Wild Bird with God in the Center: The Hermit in

Community," and a number of others. It also includes a fine bibliography

"for the study of Camaldolese history and spirituality."

For

those wishing to read about the Camaldolese there is a really fine

collection of essays on Camaldolese Benedictine Spirituality which was

noted above. It is written by OSB Camaldolese monks, nuns and oblates. It

is entitled aptly enough, The Privilege of Love and includes

topics such as, "Koinonia: The Privilege of Love", "Golden Solitude,"

"Psychological Investigations and Implications for Living Alone

Together," "An Image of the Praying Church: Camaldolese Liturgical

Spirituality," "A Wild Bird with God in the Center: The Hermit in

Community," and a number of others. It also includes a fine bibliography

"for the study of Camaldolese history and spirituality."Romuald's Brief Rule:

And for those who are not really familiar with Romuald, here is the brief Rule he formulated for monks, nuns, and oblates. It is the only thing we actually have from his own hand and is appropriate for any person seeking an approach to some degree of solitude in their lives or to prayer more generally. ("Psalms" may be translated as "Scripture".)

Sit in your cell as in paradise. Put the whole world behind you and forget it. Watch your thoughts like a good fisherman watching for fish. The path you must follow is in the Psalms — never leave it. If you have just come to the monastery, and in spite of your good will you cannot accomplish what you want, take every opportunity you can to sing the Psalms in your heart and to understand them with your mind. And if your mind wanders as you read, do not give up; hurry back and apply your mind to the words once more. Realize above all that you are in God's presence, and stand there with the attitude of one who stands before the emperor. Empty yourself completely and sit waiting, content with the grace of God, like the chick who tastes and eats nothing but what his mother brings him.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:34 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Brother Emmaus O'Herlihy, Camaldolese charism, Romuald and the Gift of Tears, Rule of Romuald, St Romuald

15 June 2015

On Lectio Divina, "Bible Roulette", etc.

[[Hi Sister, I know Lectio is an integral part of monastic spirituality;

especially for hermits. What do you suggest? Do you think the daily Mass

readings should be the source of our lectio (thereby being in tune with the

liturgy), or do you think it's better to work though the Bible systematically?

How should one structure their lectio? I don't think "Bible roulette" is

the way to go (just open it wherever) so there must be a system. What do

you suggest? Thanks!]]

[[Hi Sister, I know Lectio is an integral part of monastic spirituality;

especially for hermits. What do you suggest? Do you think the daily Mass

readings should be the source of our lectio (thereby being in tune with the

liturgy), or do you think it's better to work though the Bible systematically?

How should one structure their lectio? I don't think "Bible roulette" is

the way to go (just open it wherever) so there must be a system. What do

you suggest? Thanks!]]

Hi again, I do agree that Bible Roulette is not the way to go. It strikes me as a singularly "uncontemplative" and inattentive way to choose what one uses for lectio. It always makes me think of the NT admonition, "Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God" too. On the other hand I am not really sure what you mean by working through the Bible systematically. Some people believe they should read through the Bible starting with Genesis and then move on through every book as found in the canons. My sense is that most folks who use this approach tend to be confused by the mythical elements in Genesis and later get bogged down in the legal and history sections giving up before even reaching the New Testament.

Though the Psalms and Prophets may speak to the cries of their heart to some extent the rest tends not to do so. Culturally and in other ways it is simply inaccessible without real assistance (teachers, commentaries, lexicons, sociological and cultural commentaries, etc.). Thus, I don't recommend that any more than I recommend walking into a library, picking up the first book on the shelf nearest the entrance, and then reading through the library by progressing through the shelves one by one. For me that seems a particularly deadly way to approach or read in a library and so too, a particularly deadly way to try to read Scripture which itself is a library of many books and kinds of literature. In any case, like Bible Roulette, this approach seems to me to impose an artificial or arbitrary structure on lectio which does not pay adequate attention to one's own heart or the ways in which God is presently speaking to one. It is also blind to the riches and diversity of the library itself or to the myriad invitations it might offer us over time. It takes no time to gaze and wonder at all the library has to offer, to be grateful or intrigued or even overwhelmed with anticipation. That said, it seems to me that so long as one is spending time with Scripture in a way which does attend to one's own heart and allows God to speak to one every day, then that is what is called for.

Hermits, of course, have time for lectio as others may not so for them the approach that works may not be either/or as you have suggested but a kind of both/and. It will depend on the individual and their own responsibilities and personal inclinations. What I do and what seems to work for me is a combination of daily readings and in-depth attention to some aspect of Scripture. I use both approaches you refer to: 1) attention to the weekly readings, and 2) a second more "systematic" approach which focuses variously on one of the books being read, a particular theme (mercy, justice, heart, penance, conversion, the place of the desert in the formation of God's own People, etc.), some other book, or even a particular form of text (like the parables, the Lord's Prayer, the Passion Narratives), etc. I personally prefer using the second approach and I really miss it if I only use the daily readings. Even so, either one of these approaches can work for a reader; again, it depends on the person. Ideally they complement and reinforce one another.

Hermits, of course, have time for lectio as others may not so for them the approach that works may not be either/or as you have suggested but a kind of both/and. It will depend on the individual and their own responsibilities and personal inclinations. What I do and what seems to work for me is a combination of daily readings and in-depth attention to some aspect of Scripture. I use both approaches you refer to: 1) attention to the weekly readings, and 2) a second more "systematic" approach which focuses variously on one of the books being read, a particular theme (mercy, justice, heart, penance, conversion, the place of the desert in the formation of God's own People, etc.), some other book, or even a particular form of text (like the parables, the Lord's Prayer, the Passion Narratives), etc. I personally prefer using the second approach and I really miss it if I only use the daily readings. Even so, either one of these approaches can work for a reader; again, it depends on the person. Ideally they complement and reinforce one another.

I do both of these by using two periods of lectio each day (or one of lectio and another of related study and writing). This allows me to keep up with the liturgical readings and seasons but also focus on broader themes, literature, theological truths or positions, etc. It also allows me to do a reflection for my parish or a blog piece during most weeks. One of the tools I use in this approach is a white board where I keep random or disparate thoughts, insights, images, etc and brain storm reflections. This allows me to see various things that have struck me, pieces that might serve as seeds for further prayer, writing, study and so forth --- whether I am doing a formal period of lectio or not. The white board helps keep things "percolating". It means that generally, in one way and another, Scripture is working in my mind and heart. Besides this of course there is my regular journal where I write about what lectio has been for me, in what ways it challenges and consoles, speaks or fails to speak; I also I keep theological notes in separate books --- usually divided into themes, etc.

Regarding what is "best" though, let me say that I do believe it is important for the hermit to keep up with the liturgical year. This does not necessarily mean doing lectio with each or all of the daily readings. For instance you might find that the Sunday readings or those of another day are the source of an entire week's lectio and that this feeds you very well even as it challenges you in a way you particularly need. At the same time it may keep you in firm touch with the Church as she journeys through the year. For instance, I tend to skim the week's readings so I know what they are generally about and as I do this one or two texts in particular will catch my attention or "speak to me".

Regarding what is "best" though, let me say that I do believe it is important for the hermit to keep up with the liturgical year. This does not necessarily mean doing lectio with each or all of the daily readings. For instance you might find that the Sunday readings or those of another day are the source of an entire week's lectio and that this feeds you very well even as it challenges you in a way you particularly need. At the same time it may keep you in firm touch with the Church as she journeys through the year. For instance, I tend to skim the week's readings so I know what they are generally about and as I do this one or two texts in particular will catch my attention or "speak to me".

Those will be the "seeds" for lectio for the rest of the week. I will spend time with these "seeds", read commentaries, pray with them, journal about them, etc. Usually I will reread the contexts for these as well which is part of what the daily readings provide. Even so, I don't do lectio with or focus on every daily reading. I just can't do that; my mind and heart don't work that way. For the latter focus I really depend on the Mass homilies I hear. (One good way of allowing each day's readings some space when you are doing lectio with something else is to read them slowly once or twice before bed --- especially on the night before you will attend Mass. In that way you are ready to hear them proclaimed --- a different way of hearing them altogether because the proclaimed text is uniquely sacramental.) Otherwise, I personally do best by listening for the one or two texts or images that call out to me as I look over the week's readings and then living with those for at least the rest of the week.

Those will be the "seeds" for lectio for the rest of the week. I will spend time with these "seeds", read commentaries, pray with them, journal about them, etc. Usually I will reread the contexts for these as well which is part of what the daily readings provide. Even so, I don't do lectio with or focus on every daily reading. I just can't do that; my mind and heart don't work that way. For the latter focus I really depend on the Mass homilies I hear. (One good way of allowing each day's readings some space when you are doing lectio with something else is to read them slowly once or twice before bed --- especially on the night before you will attend Mass. In that way you are ready to hear them proclaimed --- a different way of hearing them altogether because the proclaimed text is uniquely sacramental.) Otherwise, I personally do best by listening for the one or two texts or images that call out to me as I look over the week's readings and then living with those for at least the rest of the week.

Other things besides Scripture texts can be used for lectio as well. Last week, for instance, I referred to an image of a broken and mended piece of Japanese pottery along with a comment by Sue Bender on the way the repairs highlighted the cracks with brilliant silver making the mended piece more precious than it had been before being broken. Not only was that image (along with a related image from a poem by Jan Richardson) seared in my mind on Corpus Christi, but it became something that illuminated the texts from 2 Corinthians we were reading and let me reflect on the Feast of the Sacred Heart in new and fresh ways.

Thanks for being patient with me on this question. Thanks also for reminding me I hadn't finished answering you. I mainly dumped a lot of what I had written up until today as unhelpful but I do hope this is of some assistance. If it raises more specific questions I trust you will ask.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:27 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Lectio, Lectio Divina

12 June 2015

Feast of the Sacred Heart

Today's ordinary (daily Mass) readings use the text from 2 Corinthians I spoke about earlier this week, namely, "We hold a treasure in earthen vessels so that the surpassing power will be of God and not from ourselves." You may remember that in conjunction with that text and the Feast of Corpus Christi I spoke of Sue Bender's experience of seeing a broken and mended piece of Japanese ceramics. (Marking the Feast of Corpus Christi) She wrote, [[“The image of that bowl,” she writes, “made a lasting

impression. Instead of trying to hide the flaws, the cracks were

emphasized — filled with silver. The bowl was even more precious after

it had been mended.”]]

Today's ordinary (daily Mass) readings use the text from 2 Corinthians I spoke about earlier this week, namely, "We hold a treasure in earthen vessels so that the surpassing power will be of God and not from ourselves." You may remember that in conjunction with that text and the Feast of Corpus Christi I spoke of Sue Bender's experience of seeing a broken and mended piece of Japanese ceramics. (Marking the Feast of Corpus Christi) She wrote, [[“The image of that bowl,” she writes, “made a lasting

impression. Instead of trying to hide the flaws, the cracks were

emphasized — filled with silver. The bowl was even more precious after

it had been mended.”]]

That image has been with me all this week in prayer and also as I have reflected on the various readings, especially those from Paul. It seems entirely providential to me then that this year today, the day we would ordinarily hear a reading about treasure in earthen vessels, is the Feast of the Sacred Heart. The image of this bowl --- broken, healed, and transfigured reminds me of the Sacred Heart --- traditionally the most powerful symbol we have of the indivisible wedding of human and divine and of the power of Divine Love perfected and glorified (revealed) in both human and divine weakness; thus it has provided me with a wonderfully new and fresh image of the Sacred Heart and (at least potentially) of our own hearts as well.

The heart is the center of the human person. It is a deeply distinctive anthropo-logical or human reality --- at the center of all truly personal feeling, thought, creativity and behavior. As a physical organ it stands at the center of all physical functions

within us as well empowering them, marking them with its pulsing life.

The heart is the center of the human person. It is a deeply distinctive anthropo-logical or human reality --- at the center of all truly personal feeling, thought, creativity and behavior. As a physical organ it stands at the center of all physical functions

within us as well empowering them, marking them with its pulsing life.

At the same time, it is primarily a theological term. It refers first of all to God and to a theological reality. Of course it cannot be divorced from the human (and that is the very point!), but theologically speaking, the heart is the place within us where God bears witness to God's self, where life and truth and beauty, love, integrity call to us and invite us to embrace them, reveal them in our own unique ways. As I have noted before, in some important ways it is not so much that we have

a heart and then God comes to dwell there; it is that where God dwells

within us and bears witness to himself, we have a heart. The human heart

(not the cardiac muscle but the center of our personhood) is a dialogical event where God speaks, calls, breathes,

and sings us into existence and where, in one way and degree or another,

we respond to become the people we are and (we hope) are called to be.

Everything comes together in the human heart --- or is held apart and left unreconciled by its distortions and self-centeredness. It is in the human heart broken open by love that the unity between spirit and matter is imagined, achieved, and then conveyed to the whole of creation. Here the division between earth and heaven, human and divine is bridged and healed. It is in the human heart that the unity of body and soul is achieved and celebrated.

Everything comes together in the human heart --- or is held apart and left unreconciled by its distortions and self-centeredness. It is in the human heart broken open by love that the unity between spirit and matter is imagined, achieved, and then conveyed to the whole of creation. Here the division between earth and heaven, human and divine is bridged and healed. It is in the human heart that the unity of body and soul is achieved and celebrated.

The vulnerable and broken human heart is the paradoxical place where everything is brought together in the power and mercy of God's love; it is the place where human life is transfigured and then --- through us and the ministry of reconciliation entrusted to us in Christ --- extended to the whole of creation itself. It is in the human heart that prejudices, biases, bitterness, selfishness, greed and so many other things are brought into the presence of God to be healed and transformed. At least this is the potential of the heart which is meant to be truly human and glorifies God. The human heart is holy ground and despite its limitations, distortions, darknesses, and narrownesses it is meant to shine with the expansiveness of God's creative "Yes!" Here is indeed treasure in earthen vessels.

And if this is true anywhere it is true in the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus. The Sacred Heart is the symbol of the reunion of all of reality, the place in that unique life where human life becomes completely transparent to the love of God, the sacrament par excellence of the ministry of reconciliation where human and divine are inextricably wed.

And if this is true anywhere it is true in the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus. The Sacred Heart is the symbol of the reunion of all of reality, the place in that unique life where human life becomes completely transparent to the love of God, the sacrament par excellence of the ministry of reconciliation where human and divine are inextricably wed.

Imagine then an image of the Sacred Heart similar to the image Sue Bender described, a clay pot broken and broken open innumerable times by and to the realities it dares to be vulnerable to and allows to rest within itself. Imagine too that God, that supreme potter refashions it, mends it with his love --- a love that allows the cracks to glow with the light of heaven, a light that transforms the entire pot and all who are touched by its transcendent beauty and truth. This is what we celebrate on today's Feast. The scars will remain, but transfigured --- as though mended with brilliant silver. Light and love, water and blood will pour from this heart and, in time, God will love all of creation into wholeness through Jesus' mediation and through the ministry of each of us who allow our hearts to become the Sacred places God wills them to be. We "hold" a treasure in earthen vessels. In us the surpassing power of God in Christ is at work reconciling all things to himself.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:43 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A New Heaven and a New Earth, Becoming a New Creation, Feast of the Sacred Heart, Heart as Dialogical Reality, Naming the Communion that is the Human Heart, Pouring out our Hearts

08 June 2015

The Power of Paradox Opened Our Eyes

In everything I write about spirituality or theology there is a foundational vision and truth. It is that where the real God reveals Godself paradox will abound. As I have noted before, sometimes when doing theology one of the surest signs I have strayed into heresy is an inability to point to the paradox involved! The post I put up marking Corpus Christi abounds in paradox. The questions which prompted the post seem to me to be impatient with (or perhaps incapable of) paradox and more taken with the "Greek" way of seeing things, namely thesis (the thing we are concerned with or desire), antithesis (the opposite of the thing), synthesis (a comfortable middle way, a compromise).

In everything I write about spirituality or theology there is a foundational vision and truth. It is that where the real God reveals Godself paradox will abound. As I have noted before, sometimes when doing theology one of the surest signs I have strayed into heresy is an inability to point to the paradox involved! The post I put up marking Corpus Christi abounds in paradox. The questions which prompted the post seem to me to be impatient with (or perhaps incapable of) paradox and more taken with the "Greek" way of seeing things, namely thesis (the thing we are concerned with or desire), antithesis (the opposite of the thing), synthesis (a comfortable middle way, a compromise). This approach to reality doesn't tolerate either contradiction or extremes. It does not allow for radicalness, for the radical choice or commitment! If we seek for wholeness it won't be in the midst of weakness; if we crave light we will not find it by stumbling along in the darkness of the nearest cave (or in the apparent fruitlessness of illness, etc!); if we desire to live, we will not focus our efforts on dying to self! If we wish to be rich it will not be by giving ALL we have away. If we wish to be wise, it will not be by embracing any and all of these things in acts of prodigal foolishness. Moreover, it will not be achieved in acts of radical commitment, and so forth: such commitments are simply too lacking in balance, moderation, or respectability for the Greek mind. Nor will the God of such a perspective reflect contradiction or tolerate anything compromising his purity. Is he omnipotent? Then he will not reveal himself in kenosis or weakness --- much less be perfectly or exhaustively revealed in these. Is he all good and holy? Then he will not take sin, death, or humanity itself up within himself as though union with created reality is the very goal of it all!

There are not many mansions or dwelling places for the hoi polloi in THIS God's life nor is he apt to think his divine prerogatives are NOT to be grasped at. They are. Rigidly. Unfailingly. They are to be held tightly clasped so that only divinity may touch them without defiling or denigrating them. And his Messiah? Well, what need is there of a Messiah? No one can share his life really anyway, no one can live in union with him. But even if there were a place for a Messiah --- maybe as one who meets out justice, strikes with well-deserved suffering, compels with unachievable commandments, and burdens with his capriciousness and unmitigated power, etc, he would not reveal himself in weakness or the radical love and compassion that regularly breaks his own heart and demands his very life!

But Christians, of course, believe in a very different God and model his presence in very different ways than in terms of Greek consistency or the various exclusionary "omni's" and "im's" (omnipotence, omniscience, immutability, impassibility, etc) which are so characteristic of the Greek divine ideal. Ours is the Living God of paradox instead and, as Michael Card says so very well in the following song, this God's wisdom is revealed as scandal to Jews and foolishness in the eyes of "Greeks" --- all through a Messiah and disciples who are God's own Fools.

(I have included two versions, the first done by someone else and the second done by Michael Card himself.) The professor I am most endebted to for my theology once said in one of the first theology classes I ever had that some people simply cannot think or see in terms of paradox while doing so is difficult for all of us. My prayer is that each and all of us may one day rejoice in the fact that the power of paradox, made incarnate in Jesus Christ, opened our eyes and let us glimpse and share God's own wisdom.

Posted by