Divine Wrath, Letting the Consequences of our Sin Run:

Wrath, despite the anthropomorphic limitations of language involved, is not Divine anger or a failure or refusal of God to love us. Rather, it is what happens when God respects our freedom and lets the consequences of our choices and behavior run --- the consequences which cut us off from the love and community of others, the consequences which make us ill or insure our life goes off the rails, so to speak, the consequences which ripple outward and affect everyone within the ambit of our lives. Similarly, it is God's letting run the consequences of sin which lead us to even greater acts of sin as we defend or attempt to defend ourselves against them, try futilely to control matters, and keep our hands on the reins which seem to imply we control our lives and destinies. But how can a God of Love possibly allow the consequences of sin run and still be merciful? I have one story which helps me illustrate this.

I wrote recently of the death of my major theology professor, John Dwyer. In the middle of a moral theology class focusing on the topic of human freedom and responsibility John said that if he saw one of us doing something stupid he would not prevent us. He quickly noted that if we were impaired in some way he would intervene but otherwise, no. Several of us majors were appalled. John was a friend and mentor. Now, we regularly spent time at his house dining with him and his wife Odile and talking theology into the late hours. (It was Odile who introduced me to French Roast coffee and always made sure there was some ready!) Though we students were not much into doing seriously stupid things, we recognized the possibility of falling into such a situation! So when John made this statement we looked quickly at one another with questioning, confused, looks and gestures. A couple of us whispered to each other, "But he LOVES us! How can he say that?" John took in our reaction in a single glance or two, gave a somewhat bemused smile, and explained, "I will always be here for you. I will be here if you need advice, if you need a listening ear. . . and if you

should do something stupid I will always be here for you afterwards to help you recover in whatever way I can, but I will not prevent you from doing the act itself."

We didn't get it at all at the time, but now I know John was describing for us an entire complex of theological truths about human freedom, Divine mercy, Divine wrath, theodicy, and discipleship as well: Without impinging on our freedom

God says no to our stupidities and even our sin, but he always says yes to us and his yes to us, his mercy, eventually will also win out over sin. John would be there for us in somewhat the same the merciful God of Jesus Christ is there for us. Part of all of this was the way the prospect or truth of being "turned over" to our own freedom and the consequences of our actions also opens us to mercy. To be threatened with being left to ourselves in this way if we misused our freedom --- even with the promise that John would be there for us before, after, and otherwise --- made us think very carefully about doing something truly stupid. John's statement struck us like a splash of astringent but it was also a merciful act which included an implicit call to a future free of serious stupidities, blessed with faithfulness, and marked by genuine freedom. It promised us the continuing and effective reality of John's love and guiding presence, but the prospect of his very definite "no!" to our "sin" was a spur to embrace more fully the love and call to adulthood he offered us.

How much more does the prospect of "Divine wrath" (or the experience of that "wrath" itself) open us to the reality of Divine mercy?! Thus, Divine wrath is subordinate to and can serve Divine mercy; it can lead to a wretchedness which opens us to something more, something other. It can open us to the Love-in-Act that summons and saves. At the same time it is mercy that has the power to redeem situations of wrath, situations of enmeshment in and entrapment by the consequences of one's sin. It is through mercy that God does justice, through mercy that God sets things to rights and opens a future to that which was once a dead end.

Miserando atque Eligendo, The Way of Divine Mercy:

What is critical, especially in light of Friday's readings and Francis' motto it seems to me, is that we understand mercy not only as the gratuitous forgiveness of sin or the graced and unconditional love of the sinner, but that we also see that mercy, by its very nature,

further includes a call which leads to embracing a new life. The most striking image of this in the NT is the mercy the Risen Christ shows to Peter. Each time Peter answers Christ's question, "Do you love me?" he is told, "Feed my Lambs" or "Feed my Sheep." Jesus does not merely say, "You are forgiven"; in fact, he never says, "You are forgiven" in so many words. Instead he conveys forgiveness with a call to a new and undeserved future.

This happens again and again in the NT. It happens in the parable of the merciful Father (prodigal son) and it happens whenever Jesus says something like, "Rise and walk" or "Go, your faith has made you whole," etc. (Go does not merely mean, "Go on away from here" or "Go on living as you were"; it is, along with other commands like "Rise", "Walk" "Come",etc., a form of commissioning which means. "Go now and mercify the world as God has done for you.")

Jesus' healing and forgiving touch always involves a call opening the future to the one in need. Mercy, as a single pastoral impulse, embraces our fruitless and pointless wretchedness even as it calls us to God's own creative and meaningful blessedness.

The problem of balancing mercy and justice is a false problem when we are speaking of God. I have written about this before in

Is it Necessary to Balance Divine Mercy With Justice? and

Moving From Fear to Love: Letting Go of the God Who Punishes Evil. What was missing from "Is it necessary. . .?" was the element of call --- though I believe it was implicit since both miserando and eligendo are essential to the love of God which summons us to wholeness. Still, it took Francis' comments on his motto (something he witnesses to with tremendous vividness in every gesture, action, and homily) along with the readings from this Friday to help me see explicitly that the mercification or mercifying of our world means both forgiving and calling people into God's own future. We must not trivialize or sentimentalize mercy (or the nature of genuine forgiveness) by omitting the element of a call.

When we consider that today theologians write about God as Absolute Futurity (cf Ted Peters' works,

God, the World's Future, and

Anticipating Omega), the association of mercy with the call to futurity makes complete sense and it certainly distances us from the notion of Divine mercy as something weak which must be balanced by justice. Mercy, again, is the way God does justice --- the way he causes our world to be transfigured as it is shot through with eschatological Life and purpose. We may choose an authentic future in God's love or a wounded, futureless reality characterized by enmeshment and isolation in sin, but whichever we choose it is always mercy that sets things right --- if only we will accept it and the call it includes!! Of course it is similarly an authentic future we are called on to offer one another -- just as David offered to Saul and Jesus offered those he healed or those he otherwise called and sent out as his own Apostles. Miserando atque Eligendo!! May we adopt this as the motto of our own lives just as Francis has done, and may we make it our own "modus operandi" for doing justice in our world as Jesus himself did.

In the apothegmata (sayings) of the Desert Fathers and Mothers there is a famous story. It was rooted in the personal experience of these original Christian hermits but it resonated with a line from today's reading from Paul's second letter to Timothy: [[For this reason, I remind you to stir into flame the gift of God that you have through the imposition of my hands.]] A young monk, Abba Lot, came to an elder, Abba Joseph, and affirmed that he had done all that he knew to do; everyday he did a little fasting, praying and meditating. He maintained hesychia (stillness) and purged his thoughts to the best of his ability. He wondered what else he should be doing. The story concludes, [[Standing up, the elder stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire; and he said to him, "If you are willing, you can become all flame!"]]

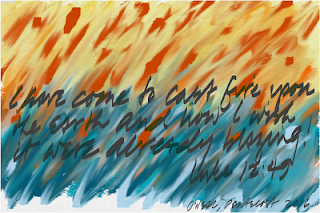

In the apothegmata (sayings) of the Desert Fathers and Mothers there is a famous story. It was rooted in the personal experience of these original Christian hermits but it resonated with a line from today's reading from Paul's second letter to Timothy: [[For this reason, I remind you to stir into flame the gift of God that you have through the imposition of my hands.]] A young monk, Abba Lot, came to an elder, Abba Joseph, and affirmed that he had done all that he knew to do; everyday he did a little fasting, praying and meditating. He maintained hesychia (stillness) and purged his thoughts to the best of his ability. He wondered what else he should be doing. The story concludes, [[Standing up, the elder stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire; and he said to him, "If you are willing, you can become all flame!"]] I suspect most of us have experienced the formal laying on of hands that occurs during the reception of some sacrament or other. If we are not ordained we would still have experienced this at confirmation and during the reception of the anointing of the sick. Some of us who were baptized as adults may have experienced this during our initiation into the Church. In every case the laying on of hands signifies the gift of the Holy Spirit and the mediation of a kind of vocational event, a call to discipleship in and of the love and presence of God in Christ. (The sacrament of anointing has been called a vocational sacrament to be sick in the Church, a call to proclaim the Gospel of God's wholeness and holiness in and through the weakness and even the relative brokenness of illness. cf. James Empereur, Prophetic Anointing) And of course there are all the other ways God lays hands on us as "his" love comforts, heals, and commissions us to God's service. I wonder if we realize the invitation these occasions represent, the invitation not merely to be touched and enlightened in so many ways by the love and presence of God, but to be so wholly transformed by him so that we become "all flame"!

I suspect most of us have experienced the formal laying on of hands that occurs during the reception of some sacrament or other. If we are not ordained we would still have experienced this at confirmation and during the reception of the anointing of the sick. Some of us who were baptized as adults may have experienced this during our initiation into the Church. In every case the laying on of hands signifies the gift of the Holy Spirit and the mediation of a kind of vocational event, a call to discipleship in and of the love and presence of God in Christ. (The sacrament of anointing has been called a vocational sacrament to be sick in the Church, a call to proclaim the Gospel of God's wholeness and holiness in and through the weakness and even the relative brokenness of illness. cf. James Empereur, Prophetic Anointing) And of course there are all the other ways God lays hands on us as "his" love comforts, heals, and commissions us to God's service. I wonder if we realize the invitation these occasions represent, the invitation not merely to be touched and enlightened in so many ways by the love and presence of God, but to be so wholly transformed by him so that we become "all flame"! This gradual but continual process of call, encounter, response, and missioning is the way the event we know as the Kingdom of God comes, first to us and then to others we meet and minister to, then to the whole of creation. And it is what the Gospel writers are calling us to today. May we each find ourselves grasped and shaken, comforted, healed and commissioned, disoriented and re-oriented by the Word of God that comes to us in Christ. And may we each come to know and believe the truth of our own potential and call --- that we are not merely meant to be touched here and there by the fire of God's love and presence, but that we are made, called, and commissioned to "become all flame" in and through that love. Amen.

This gradual but continual process of call, encounter, response, and missioning is the way the event we know as the Kingdom of God comes, first to us and then to others we meet and minister to, then to the whole of creation. And it is what the Gospel writers are calling us to today. May we each find ourselves grasped and shaken, comforted, healed and commissioned, disoriented and re-oriented by the Word of God that comes to us in Christ. And may we each come to know and believe the truth of our own potential and call --- that we are not merely meant to be touched here and there by the fire of God's love and presence, but that we are made, called, and commissioned to "become all flame" in and through that love. Amen.