I'm afraid I can't really answer your question. My understanding of the Church says it is an institution that exists in space and time with dimensions that transcend these. It is spatio-temporal at the same time it participates in the life of God, and thus, it anticipates the Kingdom of God. Thus, it makes no sense to me to suggest that no hermit should get along with the temporal Church. I am aware of one person online who divides the Church into temporal and spiritual, and also speaks as though one can be spiritual without also being temporal, but to be frank, that just makes no sense. After all, the Risen (and differently embodied) Christ is present in our world and is mediated by spatio-temporal things. This is why we have sacraments, of course! It is also why we celebrate today's Feast of the Nativity of Jesus and the beginnings of a process of Incarnation wherein Jesus grows to full stature as Son of God.

In fact, one of the most important truths (and one of the most difficult) about the reality we call Christianity is that it is rooted in historical events. God comes to us in a human being and is most exhaustively revealed in Jesus' death on the cross and resurrection from the dead. Even the appearances of the risen Jesus to the scared and dispirited disciples following his death are marked by events underscoring both the historicity of the events as well as their transcendent nature. Disciples touch the wounds, Jesus cooks and eats fish on the beach, even as he is capable of walking through walls, etc. Christianity is all about God making human history his own. It is not about a devaluing of time and space, but a transfiguring of these. This is why the Scriptures speak of God making a new heaven and a new earth where all will dwell in harmony. Our ultimate hope is that the God who reveals himself as Emmanuel will remake the whole of reality in the power of the Spirit and dwell with us in this new reality.

The idea that only the spiritual counts while the realm of the spatio-temporal should (or even can) be eschewed is a Gnostic one and thus, quite old. (It is Platonic as well, and finds contemporary representative in The Catholic stress on Sacraments demonstrates that God comes to us in the things of this earth, the temporal, if you like. Bread and Wine are raised to their highest potential (made infinitely nourishing) and made capable of truly mediating Jesus and the power to be a single family to us. Sacraments are not about the spiritual alone, but the spiritual made real in the spatio-temporal and material. The Church, and here I mean the historical reality that is called the primordial sacrament, is precisely the place where human beings are transfigured and made new by the power of the Holy Spirit. God is certainly Spirit and eternal, but what is also true is that God has chosen to be Emmanuel, God With Us, here in this world with all its spatio-temporal problems and limitations.There is no other Church than the historical one we all know. Yes, it has different dimensions, and for that reason we speak of the Church militant, or the suffering Church, or the Church triumphant, but it is still one Church, and it is a historical (spatio-temporal) reality informed by the presence of the Trinity. Catholics embracing eremitical life do so within this historical Church. That is especially true when they do so publicly, as "Catholic Hermits" in ecclesial vocations lived in the name of the Church. Moreover, we do so as human beings who are thoroughly conditioned by space and time, even as we allow God to be Emmanuel and the Holy Spirit's transfiguration of all we are and know. As we move through Advent into Christmas, it is a good time to remember that every religion except Christianity tried to escape history to bind back (re-ligio) to God. Christianity is the only faith we know whose God assumed flesh and came to dwell with us, then made a place for us (newly embodied human beings like the risen Christ) in his own eternal life, and promises a new heaven and new earth where He will be all in all.

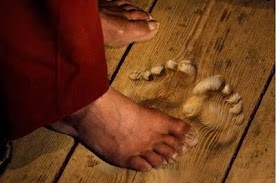

The nativity of Jesus marks the coming of this God among us, and that has always been a scandal, though especially to those with a Gnostic mindset. The scandal is increased with Jesus' crucifixion and death. A God who could allow himself to be "touched" (not to say tainted) by such realities and participate in our own humanness while raising us to participate in his divinity (theosis) was and, it appears, remains a stumbling block for some. The hermits I know take God as Emmanuel seriously. They take their own call to union with God seriously as well. And while they do live a stricter separation from the world, they are very careful in the way they define this reality. When I was newly consecrated and began this blog, I wrote the following. I think it is pertinent to your question.[[. . . First of all, "the world" does not mean "the entire physical reality except for the hermitage or cell"! Instead, the term "the world" refers to those structures, realities, things, positions, values, etc, which are antithetical to Christ and promise fulfillment or personal [dignity and] completion apart from God in Christ. Anything, including some forms of religion and piety, can represent "the world" given this definition. "The world" tends to represent escape from self and God, and also escape from the deep demands and legitimate expectations others have a right to make of us as Christians. Given this understanding, some forms of "eremitism" may not represent so much greater separation from the world as they do unusually embodied capitulations to it. (Here is one of the places an individual can fool themselves and so, needs the assistance of the church to carry out an adequate and accurate discernment of a Divine vocation to eremitical life.)]]

It seems to me that anyone who divvies reality neatly up into the temporal and the spiritual, for instance, and tries to live in this way is really fooling themselves. On this Feast of the Nativity, it is particularly important that we learn to let go of any theologies that take the embodiment of divinity and the spiritual less seriously than Christianity calls us to do. Human beings ARE embodied Spirit. We don't merely have bodies, we ARE embodied. Pope Benedict XVI (as Joseph Ratzinger), wrote in his Eschatology, Dogmatic Theology vol 9, about the Christian sense that the human soul yearns to be embodied and, following Thomas Aquinas, is actually the form of the body -- not the other way around as when the body is thought of as a container for the soul and the soul is thought to escape the body at death with heaven conceived of as the dwelling place of disembodied spirit! Both Jesus' bodily Resurrection and Ascension counter this understanding. So does Mary's Assumption.

.jpg)