[[Dear Sister, you have said that Jesus is entirely or exhaustively transparent to God and that you believe this is the same thing that the councils who came up with our Christological Dogma were saying. I have a couple of questions in that case, 1) why don't you just use the same language then and repeat the Dogmatic formula, and 2) if Jesus is both God and man, how is it he can struggle with what steps he will take in Gethsemane? Thank you.]]

Good questions, important ones, thank you. In answering the question of simply repeating dogmatic formulae and terminology my own answer needs to point out two things, 1) that while the dogmatic language and formulations of councils like Nicaea and Chalcedon were a means to an end, they were not an end in themselves, and 2) the church has made clear that theologians may well need to restate things in language that speaks better to other times and thought worlds while not rejecting the (i.e., any) dogma per se. So, first of all remember that the two natures/one person language was the best language the church had at its disposal to express the truth that in the fully human One Jesus, the world encountered the living God himself. In Jesus as fully, authentically, or exhaustively human we also meet the one in whom the creator, transcendent God is made definitively known and real in space and time and takes creation to and even into himself.

The Christological Formula:

Remember too that at the time of the Christological councils the Church was struggling to take the Christ Event seriously and to protect both parts of what I affirmed above; 1) that Jesus was truly and exhaustively human (more than you and I are because of sin), and 2) that those who encounter him also and at the same time

encounter the living God Godself. In Jesus, that God is truly and powerfully present. All human language and categories of thought will fall short of the mystery of Jesus of Nazareth and this was certainly true of the Greek categories/thought of the early Church Fathers which could not deal with paradox (which is right at the heart of the Christ Event). Thus, when someone accented Jesus' humanity it was necessarily seen to diminish the divinity one encountered in him. On the other hand, when one emphasized or accented the divinity we encountered, it necessarily meant diminishing Jesus humanity.

Imagine a pendulum hanging at rest and name that Jesus of Nazareth. Imagine theologians pushing the pendulum toward the extreme labeled "Divinity" in order to speak more and more emphatically about the way Jesus makes divinity present and encounterable in history (the world of space and time). This "pendulum" represents the way the early fathers thought world demanded they think of what was happening. If one continues to push the pendulum to its extreme in this direction (toward divinity) one was also seen as necessarily emptying Jesus of his humanity more and more, and at the extreme, when the pendulum is pushed as far as one can go in asserting the fact that in Jesus one encounters the living God, one comes up with Docetism, the heresy that Jesus merely seemed human. On the other hand, if one tries to emphasize the humanity of Jesus, Greek categories of thought and language made it necessary to push the pendulum in the direction of humanity at the expense of divinity. One came eventually to adoptionism and Arianism -- heresies in which Jesus was just a good and righteous man but not one in whom one truly encountered the living God.

Another way of describing what the Greek categories and language made necessary (and what happens on the pendulum) is that of inverse proportion which, by the way, is exactly counter direct proportion and a paradoxical way of thinking. You see, in an inverse proportion, if one increases one side of the proportion (divinity), the other side (humanity) will necessarily decrease. But back to the image of the pendulum. The solution the early Fathers came up with to end the continual problem of heresy falling into opposite heresy/heresies as the pendulum was pushed in one direction and another was to assert the two nature/one person formula. This essentially stopped the swinging and protected the truth that in the fully human one, Jesus, one also and at the same time encountered in a definitive way the living God who was the creator and redeemer of the cosmos.

Another way of describing what the Greek categories and language made necessary (and what happens on the pendulum) is that of inverse proportion which, by the way, is exactly counter direct proportion and a paradoxical way of thinking. You see, in an inverse proportion, if one increases one side of the proportion (divinity), the other side (humanity) will necessarily decrease. But back to the image of the pendulum. The solution the early Fathers came up with to end the continual problem of heresy falling into opposite heresy/heresies as the pendulum was pushed in one direction and another was to assert the two nature/one person formula. This essentially stopped the swinging and protected the truth that in the fully human one, Jesus, one also and at the same time encountered in a definitive way the living God who was the creator and redeemer of the cosmos.

Today the dogma continues to hold the pendulum steady and reminds theologians that both truths must be given full weight in writing and thinking about the Christ Event. It is a means to this end. However the dogmatic formula is not the mystery itself but a means of protecting, challenging, and verifying our language, thought, and proclamation of the mystery which stands behind this language. We not only can find other language/categories of thought to convey this mystery in order to be true to the Christological Councils, proclaiming the truth to other generations and thought worlds will demand we do so. Even so, the dogmatic formula will continue to protect the truth as we search for other ways to state and communicate the truth behind the formula (and behind whatever linguistic formulation we settle on for our time). In other words, the dogmatic or linguistic formula serves the truth, it is not the truth. It is, again, a means to an end but it is not an end in itself.

Your first Question:

The bottom line then is that I do not simply repeat the formula because I am convinced that is a sure way to fail to proclaim the mystery behind the formula to people today. We just don't think or speak in the categories used by the early Fathers and translating them into English terms we think we understand not only does not help, it leads us further astray!** I also believe it falls short of the biblical language and categories of thought --- especially those of direct proportion and paradox. Direct proportion says if one element of the ratio is increased, so must the second; if Jesus' humanity is increased, so must the divinity we encounter in and through him. Likewise, if the Divinity increases so does Jesus' humanity --- it becomes fuller, more abundant and true. Paradox says essentially the same. The dogmatic formula has an important place but it has no room for and cannot deal with paradox (though I believe it clearly calls for and maybe points to paradox as it tries to hold two contrasting realities together in unity/identity.) The need to truly encounter the living and risen Jesus --- and so too the living God who has taken us into himself just as he entered as deeply as possible into our existence in search of a counterpart --- requires different language and categories of thought if that encounter is to occur and inform my own subsequent proclamation.

Your Second Question:

Jesus is an authentically human person on a journey to live and proclaim the sovereignty of God in that life and to reveal it (make it both known and real in space and time) to the world. This means that God must be sovereign in Jesus' life and that he must learn to be attentive to this and to all the temptations he experiences to put self before the will of the one he calls Abba. He must also become more and more responsive to God rather than to all of the other powers he faces. Luke refers to this life journey when he says Jesus grew in wisdom (or grace) and stature. Incarnating the Word of God, allowing its full and exhaustive enfleshment is the work of Jesus, not of Mary, and it took Jesus the whole of his life and death. The process came to a climax in Jerusalem as the place where all the powers and principalities were centered and were even drawn by Jesus to himself. This included not merely the religious and political powers but what Paul called "powers and principalities" --- the power of evil, sin, and death which are also alive and at work in our world.

Jesus is an authentically human person on a journey to live and proclaim the sovereignty of God in that life and to reveal it (make it both known and real in space and time) to the world. This means that God must be sovereign in Jesus' life and that he must learn to be attentive to this and to all the temptations he experiences to put self before the will of the one he calls Abba. He must also become more and more responsive to God rather than to all of the other powers he faces. Luke refers to this life journey when he says Jesus grew in wisdom (or grace) and stature. Incarnating the Word of God, allowing its full and exhaustive enfleshment is the work of Jesus, not of Mary, and it took Jesus the whole of his life and death. The process came to a climax in Jerusalem as the place where all the powers and principalities were centered and were even drawn by Jesus to himself. This included not merely the religious and political powers but what Paul called "powers and principalities" --- the power of evil, sin, and death which are also alive and at work in our world.

Jesus had been speaking truth to all of these various forms of power throughout his ministry when he healed, preached, taught, exorcised, blessed, forgave, and challenged or confronted various folks. But what becomes clear to Jesus is that wonderful as they are as signs of Jesus' unique authority and the reign or sovereignty of God, no miracles or healing or exorcisms are enough to defeat the powers that are the source of so much suffering. There must be a showdown between the powers that be and God himself and that means drawing them all together, drawing them onto himself in fact while he remained entirely open and responsive to God so that God could embrace him and defeat the powers he has taken on as personal realities, personal experienced realities.

When I say Jesus struggles it is not with God nor with the choice to remain faithful and to live with integrity. But I can hear him asking himself and God if there isn't another way to achieve all that God wills for the world and God's Kingdom. Eventually though, Jesus' discernment is completed. God does not speak but I am convinced his listening presence is as active as that of any good Abba, or spiritual director. Still, the decision to continue on to the cross is Jesus' discernment as the necessary way to live his life with exhaustive faith, integrity, and love. Those contemporary theologians who say, for instance, that Jesus' cross was unnecessary must come to terms with Jesus' own discernment in this matter. In any case, we have seen Jesus struggling before this in a somewhat similar way when he was driven into the desert by the Spirit. Every time he goes apart to pray there is likely some elements of similar struggle to discern the way forward. Jesus is human like us in everything but without sin(ning). Yes, when we encounter him we also encounter the living God through and in him, but that does not mean Jesus does not have to pray or think or discern. Jesus is himself and to the extent he is entirely transparent to the living God, he is wholly, truly and exhaustively himself. That is the paradox with which Greek thought and language could not cope.

I sincerely hope this is helpful! Please feel free to write with more questions!!!

** One example of this occurring is with the words eventually translated into the English term "person". Today, the word person means an independent conscious subject and we all know that. But when the Christological Councils were held the terms (hypostasis, substance or ousia) that eventually were translated as "person" meant almost the exact opposite of what that means today. They did not mean an individual conscious subject but pointed to ways in which God possessed his own divinity. As I was taught long ago, [[[ The notion that there are three persons in God, in the sense we inevitably use the word person today, is not an assertion of faith; it is a denial of the real God because it is the refusal to allow Jesus to be the one who defines God, and the refusal to allow God to be the one who defines himself and determines the one he will be, in Jesus.]] (Dwyer, Son of Man and Son of God, A New Language for Faith, Paulist Press, 1983, p.92) Emphasis added.

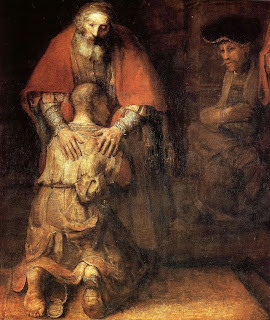

And so, in Jesus' life and active ministry, the presence of God is made real in space and time in an unprecedented way --- that is, with unprecedented authority, compassion, and intimacy. He companions and heals us; he exorcises our demons, teaches, feeds, forgives and sanctifies us. He is mentor and brother and Lord. He bears our stupidities and fear, our misunderstandings, resistance, and even our hostility and betrayals. But the revelation of God as Emmanuel means much more besides; as we move into the Triduum we begin to celebrate the exhaustive revelation, the exhaustive realization of an eternally-willed solidarity with us whose extent we can hardly imagine. In Christ and especially in his passion and death God comes to us in the unexpected and even the unacceptable place. Three dimensions of the cross especially allow us to see the depth of solidarity with us our God embraces in Christ: failure, suffering unto death, and lostness or godforsakenness. Together they reveal our God as Emmanuel --- the one who is with us as the one from whom nothing can ever ultimately separate us because in Christ those things become part of God's own life.

And so, in Jesus' life and active ministry, the presence of God is made real in space and time in an unprecedented way --- that is, with unprecedented authority, compassion, and intimacy. He companions and heals us; he exorcises our demons, teaches, feeds, forgives and sanctifies us. He is mentor and brother and Lord. He bears our stupidities and fear, our misunderstandings, resistance, and even our hostility and betrayals. But the revelation of God as Emmanuel means much more besides; as we move into the Triduum we begin to celebrate the exhaustive revelation, the exhaustive realization of an eternally-willed solidarity with us whose extent we can hardly imagine. In Christ and especially in his passion and death God comes to us in the unexpected and even the unacceptable place. Three dimensions of the cross especially allow us to see the depth of solidarity with us our God embraces in Christ: failure, suffering unto death, and lostness or godforsakenness. Together they reveal our God as Emmanuel --- the one who is with us as the one from whom nothing can ever ultimately separate us because in Christ those things become part of God's own life. As I have noted before, John C. Dwyer, my major Theology professor for BA and MA work back in the 1970's described God's revelation of self on the cross (God's making himself known and personally present even in those places from whence we exclude him) --- the exhaustive coming of God as Emmanuel --- in this way:

As I have noted before, John C. Dwyer, my major Theology professor for BA and MA work back in the 1970's described God's revelation of self on the cross (God's making himself known and personally present even in those places from whence we exclude him) --- the exhaustive coming of God as Emmanuel --- in this way: [[Jesus is rejected and his mission fails, but God participates in this failure, so that failure itself can become a vehicle of his presence, his being here for us. Jesus is weak, but his weakness is God's own, and so weakness itself can be something to glory in. Jesus' death exposes the weakness and insecurity of our situation, but God made them his own; at the end of the road, where abandonment is total and all the props are gone, he is there. At the moment when an abyss yawns beneath the shaken foundations of the world and self, God is there in the depths, and the abyss becomes a ground. Because God was in this broken man who died on the cross, although our hold on existence is fragile, and although we walk in the shadow of death all the days of our lives, and although we live under the spell of a nameless dread against which we can do nothing, the message of the cross is good news indeed: rejoice in your fragility and weakness; rejoice even in that nameless dread because God has been there and nothing can separate you from him. It has all been conquered, not by any power in the world or in yourself, but by God. When God takes death into himself it means not the end of God but the end of death.]] Dwyer, John C., Son of Man Son of God, a New Language for Faith, p 182-183.

[[Jesus is rejected and his mission fails, but God participates in this failure, so that failure itself can become a vehicle of his presence, his being here for us. Jesus is weak, but his weakness is God's own, and so weakness itself can be something to glory in. Jesus' death exposes the weakness and insecurity of our situation, but God made them his own; at the end of the road, where abandonment is total and all the props are gone, he is there. At the moment when an abyss yawns beneath the shaken foundations of the world and self, God is there in the depths, and the abyss becomes a ground. Because God was in this broken man who died on the cross, although our hold on existence is fragile, and although we walk in the shadow of death all the days of our lives, and although we live under the spell of a nameless dread against which we can do nothing, the message of the cross is good news indeed: rejoice in your fragility and weakness; rejoice even in that nameless dread because God has been there and nothing can separate you from him. It has all been conquered, not by any power in the world or in yourself, but by God. When God takes death into himself it means not the end of God but the end of death.]] Dwyer, John C., Son of Man Son of God, a New Language for Faith, p 182-183.

.jpg)