[[

Sister Laurel, I would like to become a diocesan hermit, but I can't go away to a monastery or anything like that. How would I get the formation you say I need? Also, do you know the newsletter, Raven's Bread? There are a lot of people on that and they live as hermits without formation. Some are married and claim their spouses understand their need for solitude. They just seem a lot more flexible than you do on some things. . . I wonder if you allow enough room for the Holy Spirit to work however he will in a person's life. . . I think I am already a hermit, but it sounds like you might not.]]

Formation is not an Added Burden but a Means to Freedom

Thanks for your comments and questions. One of the things I have tried to make clear in what I have written about formation is that it occurs in the silence of solitude under the hermit's own initiative and the grace of God. It is not a formal program put together or administered by a diocese, nor does it consist in formal stages like postulancy, novitiate, and so forth. It does, however, involve stages of growth, and these chart the person's movement from lone person to hermit. If one is seeking to be professed under canon 603 and a diocese believes they might be suitable for this, a diocese will monitor a candidate's own formation, her own growth as a person and transformation into a hermit as part of a process of discernment; the diocese may thus decide that certain experiences are important for the hermit's own growth and the diocese's own discernment, but this is not the same as creating and administering a formation program.

The second thing I have tried to make clear is that ANY form of life involves formation; to the extent we want to do something well and authentically there must be training, education, perseverance in the disciplines these require, and so, conversion and growth in these. Eremitical life takes skill and discipline; the solitude it demands is dangerous to those not called to it and risky even for those who are --- especially in an urban setting which militates against it at every moment. As already noted, I really believe that only the truly naive could think otherwise. While people approaching dioceses are surprised to hear a diocese won't simply admit them to vows as a hermit without a period of discernment (personal formation in living the life is implied here), I wonder if these same folks would be very surprised were they to imagine knocking on a convent door only to be told this is not how it works; they won't be professed there simply because they walk in off the street and request it! I doubt they would be surprised at such a conclusion. My insistence on the need for formation, as I have said before, is not meant to lay unnecessary burdens on the candidate, but instead to make sure they provide for ways to grow in the skills and discipline (which lead to the freedom) necessary to live 1) a paradigmatic life of assiduous prayer and penance 2) in the silence of solitude 3)

on God's behalf and on behalf of all those precious to him.

You see, one problem I run into all the time is that few people today really know what it means to live the silence of solitude. This is much more than living silence and physical solitude though it depends on these. Even fewer know what it is to live a life of assiduous prayer and penance, or really, what it means to be a desert dweller. Beyond this, still fewer imagine doing these for God's sake or the sake of others. As I have said many times, there are many forms and degrees of solitude; very few are eremitical. Stereotypes aside, whether it is email from people who cannot turn off their TV sets or disconnect from their cell phones and iPods, those who prefer not to live alone (some actually cannot do this and this is often, though not always, a different matter), folks who believe the eremitical life means simply being a lone person and doing whatever it is they can or desire to do by facile appeals to the "call of the Holy Spirit," correspondents who are married but believe that God is calling them to be hermits and celibates nonetheless, or from those who believe ANY degree of solitude in their lives means they are hermits, I am afraid I hear a lot from people who are entirely naive of the demands of the canon or who are seeking more to justify an individualistic bent and lifestyle rather than from folks who are hermits or who may ever really discern an authentic call to this.

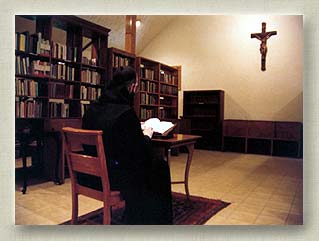

Why Spend Time in a Monastery?

With this in mind, let me explain how one of the elements I have suggested can be really helpful to diocesan hermits or candidates and why I encouraged it. I have suggested that candidates without the benefit of religious formation especially, but not only, would benefit from extended time in a monastery. I have done this because the silence and solitude in a monastery (especially smaller monasteries that accept retreatants) is of a different character than most people have ever experienced. It is lived with and for others and this is a significant quality which the hermit's own silence of solitude must also have. In a monastery it becomes very clear that the silence of solitude is there to allow God space and a continuing opportunity to reveal himself in each Sister's life and in the community as a whole. One guards both silence and solitude here so that others can seek God, find, and be found by him in the profoundly intimate ways he desires. One guards these then for God's self , for one's Sisters and also for the larger world --- some of whose inhabitants may come here hungering for a silence and solitude (or the silence of solitude) the world generally has lost entirely or cannot provide for.

There is no way to replace this experience I don't think. In Stillsong I live it in a similar but not identical way because I am alone with God

for others,

but not together with others. (The Camaldolese describe the experience I am speaking of as living alone together.) In the monastery what I experience is a shared reality and because it is shared and nurtured together (anyone eating in silence or praying silently for an hour with a dozen others will know this), it can be an intensely educative, re-vitalizing, and affirming experience for the hermit --- and I think especially for the urban hermit or the hermit who, for instance, must live with a caregiver and needs to know what is really possible to expect when people live together. So I encourage this as part of the hermit's own formation and discernment because she must be able to live something very similar in her own hermitage. She can't do this if she doesn't even know it exists or if she thinks the silence of solitude merely means the absence of external noise and closing the door on others. Additionally of course, it is really helpful to know others who are living as one does and who embrace the same values, schedule (generally speaking), praxis, etc. When one believes one is doing something strange or singular it becomes very much harder; when one knows others who are faithful to the daily discipline and praxis one is also committed to it is empowering and sustaining.

Allowing Room for the Holy Spirit:

While I am not referring to you here, your comments remind me of those I have received from others. I am surprised when I hear from folks evincing interest in profession under c 603 or in living as a hermit yet who resist making concrete commitments to regular prayer, penance, silence, solitude, or a schedule which calls for disciplined living because they "need to let the Holy Spirit guide them as to what to do". I wonder if we are speaking about the same Holy Spirit. You see, I have found that the Holy Spirit speaks to us in both the successes and failures we have in living our commitments, and less so in the absence of these and similar commitments. In other words, in my experience the Holy Spirit reminds me of how my commitments serve my vocation or not, how they allow me to grow or not, how they empower me to function or not. It is not the case that the Holy Spirit speaks out of a vacuum or like a bolt from the blue --- at least not in my general experience..

I think that suggesting commitments and structure will get in the Holy Spirit's way (which, right or wrong, is what I do hear you saying) is analogous to someone saying, "Oh I don't need to practice the violin to play it, I'll just let the Holy Spirit teach me where my fingers should go (or any of the billion other things involved in playing this instrument)." "Maybe I'll play scales if the HS calls me to; maybe I'll tune the violin if the HS calls me to. You mean I can't do vibrato without practicing it slowly? Well, maybe I will just conclude it doesn't need to be part of MY playing and the HS is not calling me to it." What I am trying to say is that if someone wants to play the violin they must commit to certain fundamental praxis and the development of foundational skills; only in so far as they are accomplished at the instrument technically will they come to know how integral this discipline and these skills are to making music

freely and passionately as the Holy Spirit impels. Otherwise the music will not soar. In fact there may be no music at all --- just a few notes strung together to the best of one's ability; the capacity for making music will be crippled by the lack of skill and technique. In other words, the Holy Spirit works in conjunction with and through the discipline I am speaking of, not apart from it.

More, my own experience is that one learns that appropriate flexibility is rooted in a disciplined life. Without the foundation I am speaking of we are not talking about flexibility but instead disorder and relative laxness and fruitlessness. Regularity does not mean rigidity, but in my own experience, one has to commit to prayer, lectio, an essential silence and solitude, regular rest, rising, recreation, meals, etc if the Holy Spirit is going to have a chance of being heard. If your criticism has to do with the fact that I am clear that married people cannot be hermits (by definition they are not solitaries), or that canon 603 grew out of Bishops' experiences with experienced monastics with significant formation who grew into an eremitical vocation and that its structure and requirements implicitly include significant formation, I plead guilty! We can all use words in any way we like, but too often doing so carelessly or without real knowledge simply empties them of meaning; in the case of the term "eremite" (or hermit), using this for any lone person (or anyone who spends any time at all in physical solitude) ensures not only that the word will be emptied of meaning but that the

truly isolated and alienated have no one to look to as a sign that such isolation can

really be redeemed and transformed into the silence of solitude.

If Time in a Monastery is Not Possible:

While the experience I am thinking of is not easily replaceable, one can break aspects of it down into significant elements and try to build one's life around those. What I would suggest you consider doing is to read about life in a monastery, and especially that you take note of the elements which monks and nuns speak about that are elemental to their lives. In order to build a life around these you will need to change the way you relate to others and the world around you in some fundamental ways. You see, I am not speaking about building IN a little silence or a little solitude or a bit of prayer or penance here or there. I am not suggesting that doing lectio once or twice a week is identical to building one's life around this, for instance. The first thing a stay in a monastery occasions in our lives is a break with our ordinary environment. To some significant extent you will need to achieve that on your own and construct a life around the elements which are central for a monastic or a hermit.

There are certain central pieces of such a life in which you may need actual instruction. Office or Liturgy of the Hours is ordinarily one of these --- especially if you choose to sing it. Just finding your way through the book can be daunting without help. (At the same time, once you get it down fundamentally you may experiment with it in many many ways and pray it in ways which are truly the fruit of the Holy Spirit.) Lectio is another and your spiritual director may be able to help you with this. Still, actual instruction in Scripture is also crucial. Quiet prayer may be something you are already skilled at, but if that is not the case, you might find a group near you that prays silently together. Doing this as a group is amazingly nurturing and supportive. Even if you cannot spend an extended period of time in a monastery, you might well manage three or four full days at a time after you get to know the community and they agree to assist you. (If you are serious about becoming a diocesan hermit your diocesan Vicar for Religious or Delegate for Consecrated Life might be able to aid you in making the connection needed and also recommend you be allowed to participate more or less fully in their daily lives for limited periods of time every few months or so --- if initial experiments in this go well.)

Thanks for your question. I think it is important to be clear about language so let me get a bit picky about some of what you have said. You say that you are discerning a vocation to religious life, but really, you are deciding at this time whether you will try a religious vocation and enter into a formal process of mutual discernment with a community or congre-gation. While discernment of course comes into play for you right now, you are not "discerning a religious vocation"; instead you are deciding whether or not TO DISCERN a religious vocation. Until you actually enter a community you may (and should) be discerning many things, but you are not (yet) discerning a religious vocation.

Thanks for your question. I think it is important to be clear about language so let me get a bit picky about some of what you have said. You say that you are discerning a vocation to religious life, but really, you are deciding at this time whether you will try a religious vocation and enter into a formal process of mutual discernment with a community or congre-gation. While discernment of course comes into play for you right now, you are not "discerning a religious vocation"; instead you are deciding whether or not TO DISCERN a religious vocation. Until you actually enter a community you may (and should) be discerning many things, but you are not (yet) discerning a religious vocation. I don't want you falling into this trap. Once you enter a congre-gation, if in fact you ever do, there will be plenty of opportunity to discern a religious vocation. The period from entrance to reception to first vows to final vows extends for up to nine years and all of these are specifically regarded as years of mutual discernment. But at this point you need to discern where God is (or rather, might well be) calling you more generally and that may be marriage just as well as it might religious life. It may be you are called to the life of a consecrated virgin, for instance. It may be as a lay associate with a religious congregation --- which means you could well be married or single and serve God in many many significant ways. Since I don't know your age or education level let me point out that education (college and graduate school) is also something you need to consider pursuing as part of ANY vocation to which God might be calling you.

I don't want you falling into this trap. Once you enter a congre-gation, if in fact you ever do, there will be plenty of opportunity to discern a religious vocation. The period from entrance to reception to first vows to final vows extends for up to nine years and all of these are specifically regarded as years of mutual discernment. But at this point you need to discern where God is (or rather, might well be) calling you more generally and that may be marriage just as well as it might religious life. It may be you are called to the life of a consecrated virgin, for instance. It may be as a lay associate with a religious congregation --- which means you could well be married or single and serve God in many many significant ways. Since I don't know your age or education level let me point out that education (college and graduate school) is also something you need to consider pursuing as part of ANY vocation to which God might be calling you.