It has been some time since I have written about the problem of lay hermits who misrepresent themselves as consecrated hermits but it is time to reprise the discussion. It is always an issue which serves as something of a flash point for those who believe consecrated hermits are demeaning those living eremitical life in the lay (baptized) state of life and it is not my preference to serve in this way. Moreover I found that in one particular case the lay hermit in question used the distinctions I was careful to articulate in order to make her own fraudulent misrepresentation more credible to those who were not knowledgeable of the critical questions her usage obscured. It's hard to write to educate only to find what one writes is used to make a fraud's misrepresentations more apparently cogent! But the simplicity and relative independence of the lives of canon 603 hermits make them relatively easy to simulate, and their consecration something far too easy to pretend to. Even so, it is important to review the issues involved.

It has been some time since I have written about the problem of lay hermits who misrepresent themselves as consecrated hermits but it is time to reprise the discussion. It is always an issue which serves as something of a flash point for those who believe consecrated hermits are demeaning those living eremitical life in the lay (baptized) state of life and it is not my preference to serve in this way. Moreover I found that in one particular case the lay hermit in question used the distinctions I was careful to articulate in order to make her own fraudulent misrepresentation more credible to those who were not knowledgeable of the critical questions her usage obscured. It's hard to write to educate only to find what one writes is used to make a fraud's misrepresentations more apparently cogent! But the simplicity and relative independence of the lives of canon 603 hermits make them relatively easy to simulate, and their consecration something far too easy to pretend to. Even so, it is important to review the issues involved.

This is so because the situation has come to the attention of CICLSAL (The Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life) in Rome because there are reports about hermits who are not consecrated whether or not they have private vows, but who, at best, believe and allow others to believe they are consecrated hermits, or at worst, actively work to mislead others and misrepresent themselves in a way which is frankly fraudulent. These latter, among other things, can be found to call themselves "religious" or "Catholic Hermits", or "consecrated Catholic hermits" and describe themselves as "part of the consecrated life of the Church"; they sometimes focus others' attention on descriptions of the liturgy during which they were (somehow) allowed to make private vows to give the errant sense these vows were received by the Church, beg money, give the sense the Church leaves them in abject poverty and dire medical circumstances while expecting they live a rigorous life of assiduous prayer, penance, and manual labor, and raise any number of other problematical issues. And so, Rome is looking to find ways to deal with the concerns of consecrated hermits, pastors, and bishops --- as well as confused faithful more generally who have been snookered by such hermits and non-hermits --- and is beginning to try to deal with the problem of lay hermits (or non-hermits!) who misrepresent themselves as consecrated hermits whether because they are simply ignorant of the Church's theology of consecrated life or because their fraud is more actively pursued by taking advantage of the theological ignorance of others.

What is really at issue?

So what is really at issue in all of this? We can certainly agree with CICLSAL that the theology of consecrated life is at stake; from my perspective this means it is our sensitivity to the specifically public and ecclesial nature of consecrated eremitical lives and our recognition of the charismatic and prophetic natures of these vocations which is most at risk. While every vocation is a gift of God to the Church and world, not every vocation is an ecclesial one; not every vocation is discerned by both Church and individual or supervised specifically by the Church because it represents a public instance of the Church's holiness and call to holiness. Not every vocation is a public vocation with public profession (e.g., public vows or propositum), public rights, obligations, and commensurate expectations by the whole People of God (and world, for that matter). But the vocation to c 603 eremitical life is all of these things and more. We, whether consecrated hermits, pastors, bishops, or canonists, treat it with the regard appropriate to it as the specific gift of God it is. At the same time neither can we obscure, misrepresent, or allow to be obscured and misrepresented any dimension of this ecclesial gift or the paradoxical way it proclaims the Kingdom of God and Gospel of Jesus Christ. To do so is to betray the gifts of God with which we have been entrusted and, to some extent, to dishonor their giver as well.

The Nuts and Bolts of the Misunderstandings Involved:

Willful fraud aside for the moment there are some significant misunderstandings driving the confusions regarding who and what are consecrated hermits. Here is where the theology of consecrated life is central as issue. It seems to me four things contribute most significantly to these misunderstandings. 1) The casual use of the term "consecrate" for an individual and ecclesially unmediated act of dedication to God, something which occurs across the entire spectrum of the Church; 2) a misreading of pars 920-921 of the CCC (the Catechism of the Catholic Church) in conjunction with the heading of the section containing these paragraphs, 3) the failure to distinguish between the consecration of baptism and that additional ecclesially mediated act by which one enters a different (i.e., consecrated) state of life (this is the failure to distinguish between the lay and consecrated states of life) and 4) a failure to distinguish between an act of profession which is always public and the making of private vows.

Willful fraud aside for the moment there are some significant misunderstandings driving the confusions regarding who and what are consecrated hermits. Here is where the theology of consecrated life is central as issue. It seems to me four things contribute most significantly to these misunderstandings. 1) The casual use of the term "consecrate" for an individual and ecclesially unmediated act of dedication to God, something which occurs across the entire spectrum of the Church; 2) a misreading of pars 920-921 of the CCC (the Catechism of the Catholic Church) in conjunction with the heading of the section containing these paragraphs, 3) the failure to distinguish between the consecration of baptism and that additional ecclesially mediated act by which one enters a different (i.e., consecrated) state of life (this is the failure to distinguish between the lay and consecrated states of life) and 4) a failure to distinguish between an act of profession which is always public and the making of private vows.

1) The casual use of the term "consecrate" for any act of personal dedication, especially for an ecclesially unmediated act of self-dedication is problematical. Vatican II, for instance, though very clear about the importance of baptismal consecration and the lay vocation, was, at the same time, very careful to distinguish between the action of God (consecratio) and the human counterpart of this action (dedicatio). Consecration is the setting of something apart as holy or for the sake of holiness and this is, properly speaking, the action of God alone. Unfortunately, we are used today to speaking of consecrating ourselves in one way and another but this is simply inappropriate and misleading. It is also inaccurate to say that Religious are consecrated by the making of vows. When individuals enter the consecrated state of life they will use vows, other forms of sacred bonds, or the propositum associated with the consecration of virgins (c. 604) to express their own dedication but this is part of the Church's mediation of God's own consecration. A corresponding solemn act of consecration (during final or solemn vows or the consecration of virgins) completes an individual's initiation into the consecrated state of life.

We refer to being consecrated in the making of vows because in this instance the dedication of vows is a synedoche where the part stands for the whole (like "head" might stand for the whole person). We use the term consecration in a similar way in relation to the part, i.e., "making vows" only in this case the whole stands for a part. At the same time, consecrated life per se is a state of life and therefore is marked by particular forms of structure and stability. For the hermit this stability is marked by a Rule of Life, profession of the Evangelical counsels, legitimate superiors and/or the supervision by Church authority (which can include the service role of delegates). All of these dimensions and more besides are part of what it means to speak of this as a state of life and beyond that, as a stable state of life which is a gift of God to the Church and world.

2) Misreading paragraphs 920-921 of the Catechism: I don't know how often this misreading of the Catechism occurs (the English version is ambiguous at best), but I do know of one case in particular where a lay hermit builds her entire case of supposedly being in the consecrated state of life on paragraphs 920-921 of the CCC. I have also received questions about this. The section is headed, "The Consecrated Life of the Church". The paragraphs noted refer to eremitical life and one crucial phrase says that one need not always make vows publicly. What is intended may be an obscure reference to the private vows some lay hermits make, but in such a case the general heading is misleading. Alternately, the CCC may have meant to refer to the "other sacred bonds" besides vows c 603 hermits are allowed to use for their public profession, but if so, the reference is, once again, awkward at best. The question of using private vows for entering the consecrated state of life can only be resolved by referring to the Church's larger theology of the consecrated state which is ALWAYS entered through public profession (c 604 uses a "propositum" rather than vows and c 603 can, as already noted, used sacred bonds other than vows but these are still acts of profession, and thus too, public ecclesial acts). While contextualizing the text in this way is critical, clarification of the meaning of the CCC text, however, would be very helpful in combating misunderstandings and outright fraudulent representations by some lay hermits.

2) Misreading paragraphs 920-921 of the Catechism: I don't know how often this misreading of the Catechism occurs (the English version is ambiguous at best), but I do know of one case in particular where a lay hermit builds her entire case of supposedly being in the consecrated state of life on paragraphs 920-921 of the CCC. I have also received questions about this. The section is headed, "The Consecrated Life of the Church". The paragraphs noted refer to eremitical life and one crucial phrase says that one need not always make vows publicly. What is intended may be an obscure reference to the private vows some lay hermits make, but in such a case the general heading is misleading. Alternately, the CCC may have meant to refer to the "other sacred bonds" besides vows c 603 hermits are allowed to use for their public profession, but if so, the reference is, once again, awkward at best. The question of using private vows for entering the consecrated state of life can only be resolved by referring to the Church's larger theology of the consecrated state which is ALWAYS entered through public profession (c 604 uses a "propositum" rather than vows and c 603 can, as already noted, used sacred bonds other than vows but these are still acts of profession, and thus too, public ecclesial acts). While contextualizing the text in this way is critical, clarification of the meaning of the CCC text, however, would be very helpful in combating misunderstandings and outright fraudulent representations by some lay hermits.

[Addendum: I wrote a post on the Latin original of this section of the CCC on July 29, 2016. It is very clear that profession is ALWAYS public; the English version of the text has interjected the phrase "while not" before always in an awkward attempt to point to the fact that vows are not always necessarily used for this PUBLIC profession. This is what the Church must make clear to pastors, bishops and candidates for c 603 life. Sorry I was not clear myself in this regard in the post at hand.]

A variation here which gives priority to the CCC text, even in interpreting c 603, includes the notion that c 603 is an option or "proviso" which postdates this section of the Catechism and which may or may not be used by the solitary consecrated hermit. Of course this misrepresentation neglects the fact that c. 603 was promulgated long before the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Canon 603 is not merely a "proviso" or option added to that of CCC; it is the way the Church establishes the vocation of the consecrated solitary hermit "in law", that is, officially in the life of the Church. On the other hand, the text of the CCC is descriptive, not prescriptive and cannot be given the kind of priority or weight some lay hermits are giving it in order to diminish the importance of the Code of Canon Law and c 603.

3) Failing to distinguish between baptismal consecration and the consecration by which one enters the consecrated state of life. It used to be common knowledge that those entering the consecrated state of life did so through a second and ecclesially mediated act of consecration which was akin to a second baptism. The notion of baptismal consecration was not widely applied; the terminology was not commonly used. Moreover, one was understood to definitively enter the "religious state" with perpetual or solemn profession. Other forms of consecrated life did not exist so there was no reason to confuse initiation into the religious state with Sacramental initiation into the Body of Christ. With Vatican II and the fresh esteem given to the lay state of life, the idea of baptismal consecration was revitalized and given wider currency in the Church as a whole. Similarly, besides the religious state the Church gave greater recognition to other forms of consecrated life (hermits, virgins, societies of apostolic life). The term "consecration" was applied to each of these and the distinction between baptismal consecration (initiation into the lay state of life) and initiation into the consecrated state was blurred and sometimes lost sight of altogether. However, the Church's theology of the consecrated state has not changed and it remains important to distinguish between this and the lay state of life (the vocational rather than the hierarchical sense of lay life) in order to honor either of these appropriately.

4) Profession versus private vows: While it is common for folks to use the verb profess or the noun profession for any act of making vows, whether public or private, this is a mistake. Profession refers to an act larger than simply the making of vows which initiates one into another state of life. Profession is therefore used to distinguish the making of public vows from the making of private vows. Private vows do not initiate a person into another state of life; public profession does. The noun profession thus never refers to the making of private vows.

A related misusage stems from the failure to understand what the Church means by the terms private and public in referring to vows. Because making vows occurs in a way where people know about them, this does not make the vows public. For vows to be public means they are associated with the assumption of public rights and obligations; it means the Church mediates these vows in a way which allows the entire Church to have certain expectations of the one who is publicly professed. Private vows mark an entirely private commitment which change nothing about a person's public rights and obligations within the Church. They are not insignificant but neither are they akin to public profession by which the Church entrusts one with public rights and obligations or signal to the church and world that the Holy Spirit is working within them in this specific way. If a lay person makes private vows they remain a lay person in the vocational sense as well as the hierarchical sense; they do not enter the consecrated state of life.

A final misusage is the application of the term "Catholic" as in "Catholic Hermit" by those who are not consecrated. This term does not merely mean one is Catholic AND a hermit. Instead it means that one lives the eremitical life in the name of the Church. Canon law is very clear that the term Catholic cannot be applied to a thing, person, or enterprise without appropriate authorization. This is true of religious institutes, TV stations, theologians, and many other things besides; one cannot append the name Catholic to the thing without the permission of the local ordinary. Catholic hermits are representatives of what the Church recognizes, governs, and supervises as eremitical life. (Catholic laity are given the right to call themselves Catholic by virtue of their baptism. To become a Catholic hermit however, one must be consecrated and thus given permission to style themselves in this way.)

Summary and call for Comments:

At this point I am merely reprising major points of misunderstanding. There are still questions to look at but I would very much like to hear from folks who have questions and thoughts about the problem. I would also like to hear from people who have run across lay hermits who claim to be consecrated and who can describe their experience. Consecrated solitary Hermits form a miniscule part of the consecrated life of the Church but the presence of fraudulent hermits falsely claiming to be consecrated can lead to dioceses failing to deal adequately with genuine instances of the eremitical call. It can lead to a cynicism and suspicion which should not exist about this vocation --- from my perspective, that is. Please let me hear your own perspective on all of this.

At this point I am merely reprising major points of misunderstanding. There are still questions to look at but I would very much like to hear from folks who have questions and thoughts about the problem. I would also like to hear from people who have run across lay hermits who claim to be consecrated and who can describe their experience. Consecrated solitary Hermits form a miniscule part of the consecrated life of the Church but the presence of fraudulent hermits falsely claiming to be consecrated can lead to dioceses failing to deal adequately with genuine instances of the eremitical call. It can lead to a cynicism and suspicion which should not exist about this vocation --- from my perspective, that is. Please let me hear your own perspective on all of this.

17 May 2018

Reprising the Problem of Lay Hermits Who Falsely Claim to be Consecrated (Part 1)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:02 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: canon 603 as ecclesial vocation, catechism par 920-921, CICLSAL, Ecclesial Vocations, Fraudulent Hermits

29 July 2016

Clarifications, Part II: Verifying the Identity and Standing of Consecrated Catholic Hermits

[[What the author seems to be saying is that any Catholic can become a consecrated Catholic hermit merely by making private vows. She DOES seem to be saying canon 603 is merely an option for solitary consecrated hermits that Bishops may or may not use --- whatever they prefer. So here are my questions: if any of this is true what prevents a completely mad person who is out of touch with reality, simply can't get along with others, and has crazy ideas of God and religion from making these private vows and then calling themselves a Catholic Hermit? What prevents them from pretending to represent the Catholic Church's understanding of eremitical life? Do pastors check out people introducing themselves as "consecrated Catholic Hermits?? And where does their supposed "consecration" come from? It doesn't seem to be from God or the Church. Does the Catechism really support [corrected typo] this the way Ms McClure says it does? You haven't explained how Ms McClure goes wrong there yet have you?]]

[[What the author seems to be saying is that any Catholic can become a consecrated Catholic hermit merely by making private vows. She DOES seem to be saying canon 603 is merely an option for solitary consecrated hermits that Bishops may or may not use --- whatever they prefer. So here are my questions: if any of this is true what prevents a completely mad person who is out of touch with reality, simply can't get along with others, and has crazy ideas of God and religion from making these private vows and then calling themselves a Catholic Hermit? What prevents them from pretending to represent the Catholic Church's understanding of eremitical life? Do pastors check out people introducing themselves as "consecrated Catholic Hermits?? And where does their supposed "consecration" come from? It doesn't seem to be from God or the Church. Does the Catechism really support [corrected typo] this the way Ms McClure says it does? You haven't explained how Ms McClure goes wrong there yet have you?]]

Now that all the vocabulary and the text of the CCC is out of the way (and has established the meaning of Consecrated Life in the section Ms McClure referred to) I can answer your other questions.

One of the reasons the Church is so careful about vocations which are mediated and celebrated with public (canonical) professions and all that goes with those is precisely to prevent the problems you envisioned and others as well. Public vocations are carefully discerned and recognized as literal gifts of the Holy Spirit to the Church and World. Canonically consecrated hermits represent God's own vocational "creation" and image the Church's vision of eremitical life; thus they are responsible for continuing the desert tradition in a divinely empowered, humanly attentive, mindful and dedicated way. Moreover, they do this in the name of the Church who has discerned the vocation with them, admitted them to profession and mediated and marked their consecration by God as an act and continuing reality in which the Church shares publicly. In this way God in Christ entrusts them with this sacred and ecclesially responsible identity, charism, and mission on behalf of God and all those God holds as precious.

One of the reasons the Church is so careful about vocations which are mediated and celebrated with public (canonical) professions and all that goes with those is precisely to prevent the problems you envisioned and others as well. Public vocations are carefully discerned and recognized as literal gifts of the Holy Spirit to the Church and World. Canonically consecrated hermits represent God's own vocational "creation" and image the Church's vision of eremitical life; thus they are responsible for continuing the desert tradition in a divinely empowered, humanly attentive, mindful and dedicated way. Moreover, they do this in the name of the Church who has discerned the vocation with them, admitted them to profession and mediated and marked their consecration by God as an act and continuing reality in which the Church shares publicly. In this way God in Christ entrusts them with this sacred and ecclesially responsible identity, charism, and mission on behalf of God and all those God holds as precious.

There are fraudulent "Catholic Hermits" out there. That's a sad but real fact. Sometimes they are just as you have described them, at least somewhat mad and out of touch with reality with crazy ideas of God, spirituality, etc. Sometimes they are entirely sane with a sound theology and spirituality but have not been able to be admitted to profession or consecration. For these persons it may simply be difficult to accept the fact that they cannot be consecrated and are asked to remain lay hermits (hermits living eremitical lives in the lay or baptismal state alone). These latter may not understand why they are not "Catholic hermits" since they are Catholic AND hermits; more, they may be WONDERFUL hermits and a gift to the Church in every way, but the truth remains --- they have not been consecrated or commissioned to live this life in the name of the Church. Unless and until they have been given and accepted this constellation of rights (and obligations) in a public (canonical) rite of profession and consecration they are not Catholic Hermits.

These latter vocations may be from God as much as any consecrated hermit's vocation is from God. The difficulty is in knowing whether that is the case or not. Similarly these vocations may be exemplary in ways we would expect either any dedicated or consecrated vocation to be, but again, there is simply no way of knowing. The Church has had no place in discerning, forming, receiving the individual's dedication, and has no role in supervising the vocation or assuring ongoing formation. For someone to live eremitical life in the name of the Church these are just some of the things which must be squared away or provided for. There is nothing excessive in these requirements; they protect people and they protect the vocation itself. In a society and culture whose driving pulse seems to be individualism and where it would be so easy for a consummate individualist to call themselves a hermit --- and even a "Catholic Hermit" at that, precautions must be taken. Because canonical hermits represent the Church in ways a lay hermit does not one must be able to trust they are who they say they are. Otherwise people can be hurt.

These latter vocations may be from God as much as any consecrated hermit's vocation is from God. The difficulty is in knowing whether that is the case or not. Similarly these vocations may be exemplary in ways we would expect either any dedicated or consecrated vocation to be, but again, there is simply no way of knowing. The Church has had no place in discerning, forming, receiving the individual's dedication, and has no role in supervising the vocation or assuring ongoing formation. For someone to live eremitical life in the name of the Church these are just some of the things which must be squared away or provided for. There is nothing excessive in these requirements; they protect people and they protect the vocation itself. In a society and culture whose driving pulse seems to be individualism and where it would be so easy for a consummate individualist to call themselves a hermit --- and even a "Catholic Hermit" at that, precautions must be taken. Because canonical hermits represent the Church in ways a lay hermit does not one must be able to trust they are who they say they are. Otherwise people can be hurt.

Generally pastors do check on the credentials of a consecrated person showing up in their parish unless, of course, the person is already well-known and established. But yes, in the case of a consecrated solitary hermit the pastor would either ask around (other pastors, et al) or contact the diocese and be sure the hermit 1) is professed and consecrated under canon 603, and 2) is in good standing with the diocese or chancery. Diocesan hermits, as I have noted before have a certain stability of place and cannot move from the jurisdiction of their legitimate superior (local ordinary) unless the bishop of a new diocese agrees to become responsible for her and for her vows.

Generally pastors do check on the credentials of a consecrated person showing up in their parish unless, of course, the person is already well-known and established. But yes, in the case of a consecrated solitary hermit the pastor would either ask around (other pastors, et al) or contact the diocese and be sure the hermit 1) is professed and consecrated under canon 603, and 2) is in good standing with the diocese or chancery. Diocesan hermits, as I have noted before have a certain stability of place and cannot move from the jurisdiction of their legitimate superior (local ordinary) unless the bishop of a new diocese agrees to become responsible for her and for her vows.

Most diocesan hermits possess a sealed (meaning embossed or stamped with the diocesan seal) and notarized affidavit issued at profession testifying to their canonical standing and providing the date and place of profession and consecration. (This is akin to a baptismal or other sacramental certificate and a copy is kept in the person's file at the chancery.) A pastor could easily ask to see such a document (or a hermit could simply present it as a courtesy); in its absence he might ask who the hermit's legitimate superior is --- expecting the response to be the local bishop and probably an assigned or chosen delegate. If the hermit is a member of an institute of consecrated life and is in the parish while on exclaustration, for instance, then she would again have the proper paper work to establish her bona fides for the pastor. When this is all squared away the way is open for introducing the hermit to the larger parish membership in a way which establishes the authenticity of the hermit's ecclesial identity and place in the life of the faith community. (None of this need detract from the significant role lay hermits play in the life of a faith community by the way, and they too can be identified as the lay hermits they are.)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

8:44 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: canonical standing --- relational standing, consecrated v dedicated hermits, Fraudulent Hermits, legitimate superior

09 November 2015

Fraudulent Hermits a Problem Through History?

Thanks for writing again. Yes, as I recall the canonist was reported to have said c 603 itself was a revision of something in the 1917 Code and also that it was developed in order to prevent abuses as well as to accommodate those who desired an "official stamp of approval". While the 1983 Code of Canon Law is a revision of the 1917 Code (which may have been what this canonist actually said) there was NO provision for hermits in the 1917 Code so c 603 per se is not a revision of anything in universal law. Neither was canon 603 itself developed to deal with abuses. Solitary eremitical life had pretty much died out in the Western Church --- at least in the contemporary Church. If there were lay hermits around they were neither a major problem nor instance of abuse of the eremitical life. Meanwhile the hermits that existed in semi-eremitical institutes like the Camaldolese or Carthusians were sufficiently governed by Canon Law and the institutes' own proper law (constitutions and statutes). A new canon would have been unnecessary for these reasons.

However in the history of eremitical life there have been various attempts to deal with both authentic and false or fraudulent hermits. Mark Miles documents some of this history in his Dissertation, Canon 603 Diocesan Hermits in the Light of Eremitical Tradition. He notes that until the Council of Trent (16th C) there were uneven attempts to deal with this form of life at diocesan synods -- though with the Gregorian reforms there were some papal attempts to tighten controls over this form of life. After the Council of Trent bishops were "encouraged to use whatever means necessary to reform the life of clergy and religious" and the result was that many countries "adopted the medium of the diocesan synod to regulate the relationship between hermit and priest, and hermit and bishop." Spain and France in particular adopted such means of regulating individual hermits including a pledge of obedience to the diocesan bishop. In the case of authentic hermits this was done "to offer security and protection" to these persons.

But fraudulent hermits (or those who were false in the sense of being inauthentic) were indeed a problem and a number of steps were taken to control this. In the sixth century hermits were seen as a kind of monk and were required to spend a period of time in a monastery in order to prove his vocation. Hermits who spent "strict training in a monastery" would then be allowed to leave to live as a "full solitary". Miles notes that only then would their "aversion to common life [be] seen as legitimate." (Though technically correct perhaps, I find the historical use of the term aversion here strikingly infelicitous!) After the Council of Trent Pope Benedict XIV proposed a set of norms for the hermits in the diocese of Rome and encouraged other dioceses to do something similar. This work by Benedict XIV recognized "four kinds of hermits that had existed up to that point: [those] linked to a religious order, [those] that lived as a group or congregation under the rule and direction of the diocesan bishop, those that lived completely alone and also under the direction of the bishop and finally, the false hermits." Miles DHET, 85 (Emphasis added.)

With regard to the last group, Spain (including its colonies and territories), for instance, generally required hermits "to be received and instituted in a legitimate way by the diocesan Bishop and remain obedient to him." Miles writes, "Those unwilling to follow this practice were outlawed in most parts of the territory (Mexico)." A number of punishments were associated with infringements of the established legal practice including excommunication (some dioceses in Spain) and in some "false hermits might even find themselves in jail." (Miles, 86) In most countries bishops were similarly directly responsible for the hermits living in his diocese. Minimum ages (40 years) were set by synods as were the permissions or prohibitions of single women pursuing this vocation, candidates were vetted, conditions for moving from one hermitage to another were established as were conditions re wearing a habit and the nature of the habit (e.g., it could not be the same as those worn by established and recognized congregations of monks), etc. Other conditions that were legislated included conditions of life in cell: women were prohibited entry, solitaries could not leave their cells and loiter outside, other situations leading to scandal were regulated and so were the norms for begging for alms. (Especially hermits were not allowed to range far and wide or beg at all hours. The vocation was solitary and sedentary rather than one of peripatetic mendicancy and this had to be respected.)

With regard to the last group, Spain (including its colonies and territories), for instance, generally required hermits "to be received and instituted in a legitimate way by the diocesan Bishop and remain obedient to him." Miles writes, "Those unwilling to follow this practice were outlawed in most parts of the territory (Mexico)." A number of punishments were associated with infringements of the established legal practice including excommunication (some dioceses in Spain) and in some "false hermits might even find themselves in jail." (Miles, 86) In most countries bishops were similarly directly responsible for the hermits living in his diocese. Minimum ages (40 years) were set by synods as were the permissions or prohibitions of single women pursuing this vocation, candidates were vetted, conditions for moving from one hermitage to another were established as were conditions re wearing a habit and the nature of the habit (e.g., it could not be the same as those worn by established and recognized congregations of monks), etc. Other conditions that were legislated included conditions of life in cell: women were prohibited entry, solitaries could not leave their cells and loiter outside, other situations leading to scandal were regulated and so were the norms for begging for alms. (Especially hermits were not allowed to range far and wide or beg at all hours. The vocation was solitary and sedentary rather than one of peripatetic mendicancy and this had to be respected.)It seems clear from all of this that the term "false hermits" had two overlapping senses. The first was folks who were under no ecclesiastical authority or direction but who wandered the diocese calling themselves hermits, begging for alms, dressing in habits sometimes mimicking those of clerics and monks, and generally living a life of pretense in this way. The purpose of these varied diocesan norms was indeed to prevent false hermits of this type from operating with impunity. Additionally the norms helped protect the marriage bond and Sacrament of matrimony by preventing married persons from becoming hermits (all Spanish dioceses legislated this) and some excluded single women from living an eremitical life. (Thank God some other countries did not adopt this norm!) The second type of false hermit was as important, namely legitimate hermits who were giving scandal or substituting individualism for an eremitism the Church recognized as authentic. These too were living lives of pretense though it was the more serious pretense of hypocrisy and actual infidelity to an ecclesial commitment and commission.

The distinction between these norms and canon 603 comes from the fact that the contem-porary Latin Church had not had solitary hermits for at least a century and a half. Dioceses were not plagued with false hermits in at least the first sense. Moreover, as I have explained before monks in solemn vows were discovering eremitical vocations but had to be secularized in order to pursue their call to be hermits. Bishop de Roo wrote an intervention for the Second Vatican Council listing five positive reasons (cf On Betraying the Eremitical Vocation) for recognizing eremitical life as a state of perfection. He was not proposing the Church deal with abuses. My objections to what the canonist was supposed to have said dealt with the application of general historical conditions to the development of canon 603 per se. In no way would I try to suggest diocesan canons were not formulated to fight abuses nor that c 603 could be used in this way if necessary, but the fact is that was not the situation leading to canon 603 itself. This is not why canon 603 was created and promulgated.

By the way, it is also important to note that contrary to the arguments of those who say c 603 is a needless and even destructive instance of increased institutionalization of eremitical life, when viewed against this background c 603 actually represents a less onerous and more flexible instance of canonical institutionalization than has often been the case in Church history. I would argue this is precisely because its roots are positive and an attempt to codify in some protective and nurturing way a precious and prophetic charisma of the Holy Spirit. Similarly, the argument that canon 603 is a deviation from and even a distortion of the traditional practice of just going off on one's own to live as a hermit is even more clearly specious than I have demonstrated in the past. Far from being the norm for hermits in the Roman Catholic Church, the examples mentioned above point to a widespread ecclesiastical practice of discouraging or even prohibiting this form of eremitical life as "false". The Church has always acted (though perhaps not always carefully or consistently enough) in a variety of ways to protect a fragile but vital vocation from multiple kinds of "falseness." In this, and in other things, law is used in an attempt to serve love.

References in this article are mainly taken from the doctoral dissertation mentioned. I am not sure how available it is generally but again, the work is entitled, Canon 603 Diocesan Hermits in the Light of Eremitical Tradition by Mark Gerard Miles. Gregorian Pontifical University, Rome 2003.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:52 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: becoming a Catholic Hermit, Canon 603 - history, Canon 603 Dissertation, Fraudulent Hermits, institutionalization of eremitical life

29 September 2015

On Anonymity and Accountability for Hermits

v [[Dear Sister. What are your views on anonymity for hermits? I read an article today by a Catholic Hermit who has decided to remain anonymous since that helps her prevent pride. You choose not to remain anonymous so I am wondering about your thinking is on this.]]

[[Dear Sister. What are your views on anonymity for hermits? I read an article today by a Catholic Hermit who has decided to remain anonymous since that helps her prevent pride. You choose not to remain anonymous so I am wondering about your thinking is on this.]]

It's a timely question and an important one not least because it points to the responsible nature of ecclesial vocations. The first thing to remember is that if one claims to be a Catholic hermit, that is one who lives eremitical life in the name of the Church via profession (always a public act) and consecration, then one has been commissioned to live a public ecclesial vocation. If one claims the title "Catholic Hermit" or "consecrated hermit", etc., in creating a blog or other website, for instance, then one really doesn't have the right to remain entirely anonymous any longer. This is because people who read the blog have commensurate rights to know who you are, who supervises your vocation, who professed and consecrated you and commissioned you to live this life in the name of the Church. If they have concerns with what you write then they must be able to contact you and, if really necessary, your legitimate superiors.

Ways of Maintaining Appropriate Accountability:

One thing that is possible, of course, is to say that this blog (etc) is the blog of a "Diocesan Hermit of the Diocese of Oakland," for instance, without providing one's given name. In doing so I would still be maintaining accountability to the Church for this vocation and what comes from it. If there is ever a serious concern, then the Diocese of Oakland (for instance) will know whose blog is being referenced. (In this case, they may not ordinarily concern themselves with my everyday writing because they do not micromanage my activities --- my delegate would tend to know more about my blogging, I think --- but they will know whose blog this is and deal appropriately with serious complaints or concerns that might arise.) However, it seems to me one still needs to provide a way for folks to contact one so the chancery isn't turned into the recipient of relatively trivial communications which are an actual imposition. (I, for instance, do not usually provide my hermitage address, but people who prefer not to email may write me at my parish. This would work even if I did not give my name but used "Diocesan Hermit" instead because the parish knows precisely who I am and provides a mailbox for me.)

A second solution is to blog or whatever the activity without claiming in any way to be a Catholic hermit, Diocesan hermit, consecrated person, professed religious, etc. As soon as one says I am a Catholic Hermit (or any version of this) one has claimed to be living a vocation in the name of the Church and the public writing one does, especially if it is about eremitical life, spirituality, etc, is something one is publicly accountable for as a piece of that living. So, the choice is clear, either write as a private person and remain anonymous (if that is your choice) or write as a representative of a public vocation and reveal who you are --- or at least to whom you are legitimately accountable. Nothing else is really charitable or genuinely responsible.

A second solution is to blog or whatever the activity without claiming in any way to be a Catholic hermit, Diocesan hermit, consecrated person, professed religious, etc. As soon as one says I am a Catholic Hermit (or any version of this) one has claimed to be living a vocation in the name of the Church and the public writing one does, especially if it is about eremitical life, spirituality, etc, is something one is publicly accountable for as a piece of that living. So, the choice is clear, either write as a private person and remain anonymous (if that is your choice) or write as a representative of a public vocation and reveal who you are --- or at least to whom you are legitimately accountable. Nothing else is really charitable or genuinely responsible.

Some may point to books published by an anonymous nun or monk, books published with the author "a Carthusian monk" (for instance), as justification for anonymity without clear accountability, but it is important to remember that the Carthusian Order, for instance, has its own censors (theologians and editors) and other authorities who approve the publication of texts which represent the Order. The Carthusians are very sensitive about the use of the name Carthusian or the related post-nomial initials, O Cart., and they use these as a sign of authenticity and an act of ecclesial responsibility. (The same is true of the Carthusian habit because these represent a long history which every member shares and is responsible for.) The Order is in turn answerable to the larger Church and hierarchy who approve their constitutions, etc. Thus, while the average reader may never know the name of the individual monk or nun who wrote the book of "Novices Conferences" for instance, nor even know the specific Charterhouse from whence they wrote, concerns with the contents can be brought to the Church and the Carthusian Order through appropriate channels. This ensures a good blend of accountability and privacy. It also allows one to write without worrying about what readers think or say while still doing so responsibly and in charity. Once again this is an example of the importance of stable canonical relationships which are established with public profession and consecration --- something the next section will underscore.

The Question of Pride:

It is true that one has to take care not to become too taken with the project, whatever it is, or with oneself as the author or creator. With blogs people read, ask questions, comment, praise, criticize, etc, and like anything else, all of this can tempt one to forget what a truly tiny project the blog or website is in the grand scheme of things. But, anonymity online has some significant drawbacks and a lack of honesty and genuine accountability --- which are essential to real humility I think --- are two of these. How many of us have run into blogs or message boards which lack charity and prudence precisely because the persons writing there are (or believe they are) anonymous? Some of the cruelest and most destructive pieces of writing I have ever seen were written by those who used screen names to hide behind.

It is true that one has to take care not to become too taken with the project, whatever it is, or with oneself as the author or creator. With blogs people read, ask questions, comment, praise, criticize, etc, and like anything else, all of this can tempt one to forget what a truly tiny project the blog or website is in the grand scheme of things. But, anonymity online has some significant drawbacks and a lack of honesty and genuine accountability --- which are essential to real humility I think --- are two of these. How many of us have run into blogs or message boards which lack charity and prudence precisely because the persons writing there are (or believe they are) anonymous? Some of the cruelest and most destructive pieces of writing I have ever seen were written by those who used screen names to hide behind.

Unfortunately this can be true of those writing as "Catholic Hermits" too. I have read such persons denigrating their pastors (for having no vocations, caring little for the spiritual growth of their parishioners, doing literally "hellish" things during Mass, etc), or denigrating their bishops and former bishops (for whining, lying and betraying the hermit to the new bishop) --- all while remaining relatively anonymous except for the designation "Catholic Hermit" and the name of her cathedral. How is this responsible or charitable? How does it not reflect negatively on the vocation of legitimate Catholic hermits or the eremitical vocation more generally? Meanwhile these same bloggers criticize Diocesan hermits who post under their own names accusing them of "pride" because they are supposedly not sufficiently "hidden from the eyes of" others.

Likewise, over the past several years I have been asked about another hermit's posts which have left readers seriously concerned regarding her welfare. This person writes (blogs) about the interminable suffering (chronic pain) she experiences, the lack of heat and serious cold she lives in in Winter months which causes her to spend entire days in bed and under blankets and left her with pneumonia last Winter; she writes of the terrible living conditions involving the ever present excrement of vermin --- now dried and aerosolized, holes in walls (or complete lack of drywall and insulation), continuing lack of plumbing (no toilet) or hot water despite her marked physical incapacities, the fact that she cannot afford doctors or medicines or appropriate tests and may need eventually to live in a shelter when her dwindling money runs out. Unfortunately, because all of this is written anonymously by a "consecrated Catholic Hermit" presumably living eremitical life in the name of the Church, it raises unaddressable questions not only about her welfare but about the accountability of her diocese and the soundness and witness of the contemporary eremitical vocation itself.

This poster's anonymity means that those who are concerned can neither assist her nor contact her diocese to raise concerns with them. Here anonymity conflicts with accountability. While it is true diocesan hermits are self-supporting and have vows of poverty readers have, quite legitimately I think, asked if this really the way the Church's own professed and consecrated hermits live. Does the Church profess and consecrate its solitary hermits (or facilely allow them to transfer to another diocese) and then leave them to struggle in such circumstances without oversight or assistance? Is this the kind of resource-less candidate the Church commissions to represent consecrated eremitical life? Would this be prudent? Charitable? Is it typical of the way consecrated life in the church works? Does a hermit's diocese and bishop really have nor exercise no responsibility in such cases? How are such hermits to be helped?? Unfortunately, the combination of this poster's relative anonymity and her lack of accountability, prudence, and discretion can be a serious matter on a number of levels.

In other words while pride may be a problem (or at least a temptation!) for those of us who blog openly, it may well be that anonymity itself may lead to an even greater arrogance whose symptoms include writing irresponsibly and without prudence, discretion, or real accountability. Thus I would argue that anonymity can be helpful so long as one still exercises real accountability. Importantly, one needs to determine the real motives behind either posting publicly or choosing anonymity. Simply choosing anonymity does not mean one is exercising the charity required of a hermit. It may even be a piece of a fabric of deception --- including self deception. For instance, if one chooses anonymity to prevent others from learning they are not publicly professed, especially while criticizing the "pride" of diocesan hermits who choose to post openly, then this is seriously problematical on a number of levels.

In other words while pride may be a problem (or at least a temptation!) for those of us who blog openly, it may well be that anonymity itself may lead to an even greater arrogance whose symptoms include writing irresponsibly and without prudence, discretion, or real accountability. Thus I would argue that anonymity can be helpful so long as one still exercises real accountability. Importantly, one needs to determine the real motives behind either posting publicly or choosing anonymity. Simply choosing anonymity does not mean one is exercising the charity required of a hermit. It may even be a piece of a fabric of deception --- including self deception. For instance, if one chooses anonymity to prevent others from learning they are not publicly professed, especially while criticizing the "pride" of diocesan hermits who choose to post openly, then this is seriously problematical on a number of levels.

At the same time some authentic Catholic hermits choose to let go of their public vocational identities for a particular limited project (like participation in an online discussion group or the authoring of a blog) and write as private persons. This is a valid solution --- though not one I have felt justified in choosing myself --- because one does not claim to be a Catholic hermit in these limited instances. And of course some of us decide simply to be up front with our names, not because we are prideful, but because for us it is an act of honesty, responsibility, and charity for those reading our work or who might be interested in the eremitical vocation. The bottom line in all of this is that anonymity may or may not be a necessary piece of the life of the hermit. For that matter it may be either edifying or disedifying depending on how it protects an absolutely non-negotiable solitude or privacy and allows for true accountability or is instead used to excuse irresponsibility, disingenuousness, or even outright deception.

Summary:

The hiddenness of the eremitical life is only partly that of externals. More it has to do with the inner life of submission to the powerful presence of God within one's heart. Sometimes that inner life calls for actual anonymity and sometimes it will not allow for it. Since the vocation of the Catholic hermit is a public one any person posting or otherwise acting publicly as a Catholic hermit has surrendered any right to absolute anonymity; they are accountable for what they say and do because they are supposedly acting in the name of the Church. The need for and value of anonymity must be measured against the requirements of accountability and charity.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:00 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: accountability, anonymity, authentic and inauthentic eremitism, Ecclesial Vocations, Eremitical Hiddenness, Essential Hiddenness, Fraudulent Hermits, public vocations

13 July 2015

Diocesan Hermits in the Archdiocese of Seattle?

Thanks for your questions. The simplest answer re the canonical standing of the person in question is to ask her! That is always the first step. If this is somehow inadequate or is impossible, then the next step is to contact the local parish and see if they know the answer. Finally, you can call the chancery and ask them if there is a consecrated (c 603) hermit living on Vashon Island. If you know the person by name they will tell you whether she is a diocesan hermit and usually whether she is in good standing with the diocese, but they are not going to give you any further details regarding the person if they know her at all. If they ask if there are problems just let them know you merely want to verify the person's canonical standing unless (as you seem to imply) there is something more involved.

The Archdiocese of Seattle has at least one diocesan hermit that I know of. But he is male; his name is Brother Jerry Cronkhite and he was professed on May 14, 2012 in the Cathedral of St James. I mention this to indicate that the Archdiocese HAS used canon 603 and therefore are clearly open to doing so. Some have tried to argue that some dioceses choose "the private route" rather than c 603, so I want to underscore this argument is especially specious in this case. I know of two lay hermits either in Seattle or the Tacoma area close by Vashon Island. Still, for information on diocesan hermits (solitary consecrated hermits) your best source is the chancery. We diocesan hermits in the US are a small 'community' and a small number of those do belong to the Network of Diocesan Hermits, but I doubt any one of us knows all or even most of the others. (By the way, there is no central data base on c 603 hermits. Rome has begun keeping statistics on us but at this point it is only the individual dioceses that have the information on those professed in the hands of local Bishops.)

The Archdiocese of Seattle has at least one diocesan hermit that I know of. But he is male; his name is Brother Jerry Cronkhite and he was professed on May 14, 2012 in the Cathedral of St James. I mention this to indicate that the Archdiocese HAS used canon 603 and therefore are clearly open to doing so. Some have tried to argue that some dioceses choose "the private route" rather than c 603, so I want to underscore this argument is especially specious in this case. I know of two lay hermits either in Seattle or the Tacoma area close by Vashon Island. Still, for information on diocesan hermits (solitary consecrated hermits) your best source is the chancery. We diocesan hermits in the US are a small 'community' and a small number of those do belong to the Network of Diocesan Hermits, but I doubt any one of us knows all or even most of the others. (By the way, there is no central data base on c 603 hermits. Rome has begun keeping statistics on us but at this point it is only the individual dioceses that have the information on those professed in the hands of local Bishops.)The conclusion and accusation that one is a "fake hermit" is a serious one. The charge ought not be leveled without real cause. While the term Catholic Hermit is authoritatively used by hermits with public vows and consecrations to indicate they live as hermits in the name of the Church, there are a handful of lay hermits (hermits in the lay state of life) who use the descriptor without having been authorized to do so. Some simply don't realize what they are doing is inappropriate. The person you are speaking of may well be a lay Catholic and hermit with or without private vows. The lay eremitical life, when lived authentically, is an entirely valid way to live eremitical life within the Church; it simply means the baptized person is living a private commitment in the lay state. She is not a religious (though she may be discerning admission to canon 603 with the diocese) and cannot claim to be living the eremitical life in the name of the Church. Still such a hermit lives her life as a Catholic lay person and represents a significant and living part of the eremitical tradition. Such a calling is to be esteemed.

Unfortunately, it cannot be denied that some individuals and some lay hermits do consciously and falsely try to pass themselves off as professed Religious or consecrated hermits. They either do know what they are doing is inappropriate and don't care, or they are wholly ignorant of the meaning of what they are doing I guess. Some do seem to believe one becomes a religious by making private vows --- which is simply not the case. Some seem to need a way to validate the failures in their own lives or desire a way to "belong" or have status they have not been granted otherwise (for genuine ecclesial standing is extended to the person and embraced freely by them; it is never merely taken). Some relative few use this as a way to beg for money or scam others. Others live isolated lives which are nominally Catholic, but without a Sacramental life or any rootedness in the local community. They validate this with the label 'hermit' but, whether lay persons or not, they are not living eremitical lives as understood and defined by the Church. Even so, let me reiterate, the conclusion of fraud is not one a person ought to leap to nor come to without serious cause.

By the way, one final possibility exists. You asked if Catholic hermits and canonical hermits are the same thing and the answer is yes. All Catholic hermits are canonical and live their vocation in the name of the Church. But some of these are solitary (c 603) and others belong to canonical communities (institutes). If the hermit you are speaking about belongs to a canonical community but is, for some valid reason, living on her own (say, on exclaustration while trying the eremitical vocation, for instance), then she will tell you what community she is professed with and be able to name her legitimate superior. (If she is lay person or former religious working with the Archdiocese to discern a vocation to canonical eremitism then she will tell you that too.) Again, while one should not pry, public vocations are just that and religious are answerable for these. Her identity, if she claims to be publicly professed, shouldn't be a secret, especially if she wishes to be known as a hermit. Similarly one shouldn't simply contact the chancery for any little thing nor without meaningful justification; however, if you have significant concerns for or about this person, then, presuming you have spoken to the person herself first to clarify matters, you can raise those with her legitimate superior or with Archbishop Sartain or the Vicar for Religious in the Archdiocese at the same time.

So, to summarize, in your situation the simplest way to determine if the hermit in question is a canonical hermit and thus too, a Catholic Hermit who lives her life in the name of the Church, is to ask her whether she is a lay hermit (perhaps but not necessarily privately vowed or dedicated) or publicly professed and consecrated; if she says the latter then you may ask her who her legitimate superior is. Diocesan hermits will always name the local diocesan Bishop as their legitimate superior for their vows were made in his hands. FYI, it will not be a Bishop in another diocese, nor will it be another priest, or a spiritual director (even if this is a bishop), for instance. Nor, again, will a canonical hermit ever tell you her diocese doesn't require legitimate superiors or has chosen to go the "private route." If the diocese has not used canon 603 yet (again, not applicable to the Archdiocese of Seattle since they have at least one c 603 hermit) and the person has private vows they are NOT made under the auspices of the diocese per se. If questions or serious concerns remain turn to the parish and if necessary, to the chancery itself. Ask to speak to the Vicar for Religious (or the Vicar for Consecrated Life). S/he will certainly know the person if they are a c 603 (publicly professed solitary) hermit.

So, to summarize, in your situation the simplest way to determine if the hermit in question is a canonical hermit and thus too, a Catholic Hermit who lives her life in the name of the Church, is to ask her whether she is a lay hermit (perhaps but not necessarily privately vowed or dedicated) or publicly professed and consecrated; if she says the latter then you may ask her who her legitimate superior is. Diocesan hermits will always name the local diocesan Bishop as their legitimate superior for their vows were made in his hands. FYI, it will not be a Bishop in another diocese, nor will it be another priest, or a spiritual director (even if this is a bishop), for instance. Nor, again, will a canonical hermit ever tell you her diocese doesn't require legitimate superiors or has chosen to go the "private route." If the diocese has not used canon 603 yet (again, not applicable to the Archdiocese of Seattle since they have at least one c 603 hermit) and the person has private vows they are NOT made under the auspices of the diocese per se. If questions or serious concerns remain turn to the parish and if necessary, to the chancery itself. Ask to speak to the Vicar for Religious (or the Vicar for Consecrated Life). S/he will certainly know the person if they are a c 603 (publicly professed solitary) hermit.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:02 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Archdiocese of Seattle, Canon 603, Fraudulent Hermits, importance of lay eremitical vocations, Lay hermits vs diocesan hermits

21 March 2015

Some Reflections on Why Canon Law is Important to the Diocesan Hermit

[[Hi Sister, have you always been interested in Canon Law? Do diocesan hermits have to have this kind of interest or knowledge? (Suppose I couldn't care less about this kind of stuff, could I still be a hermit?) One friend said that hermits usually don't care about laws, their freedom is contrary to that and everything I have read about hermits stress their freedom. Is there some way in which he is right or are consecrated hermits kind of "law and order types"? Are those hermits who do their own thing misrepresenting this vocation?]]

Have I always been interested in Canon Law? Nope, definitely not. My own interest is very limited and circumscribed, namely, it is confined to canon 603 and to the life defined there. In a broader sense that and my own history means being interested in the canons on religious life as well; after all a number of those apply to those professed as c 603 hermits, but I can't say canon law per se holds much interest for me apart from the life I have been commissioned to live in the name of the Church. Theology is a much more compelling and pervasive interest for me and my interest in this canon specifically often has to do with the theology and spirituality it seeks to express and protect. Often this involves ecclesiology (theology of the Church) and the way individuals are made responsible for embodying theological truth.

Thus, my interest has also grown over time. It has been spurred by several ideas which are integral to canon 603, not least, 1) the ecclesial nature of the vocation, 2) the amazingly beautiful combination of non-negotiable elements and individual flexibility c 603 codifies, 3) the responsiveness of this canon to history and its capacity to reflect and protect the solitary eremitical tradition as part of the Church's own patrimony, and 4) the lesson that canon law follows life and law serves love. I don't think we necessarily always see these things clearly in canon law (or any law for that matter) but we do see it in the case of canon 603. Especially important here and with regard to #1 above is the way the canon (and canonical standing more generally) creates stable relationships which are essential for ecclesial vocations. The idea that the canon legislates, establishes, and protects those relationships necessary to live this life well and in a prophetic way was tremendously surprising and impressive to me.

While canonical hermits do not usually need much of this kind of knowledge (we have canonists and Vicars who handle canonical details with regard to vows and other things), some, like myself, are interested to the degree that c 603 is new and codifies in universal law a new form of consecrated life. Thus, we tend to be interested in this canon, how it came to be, why it exists, and so forth, and some few of us reflect on the way the canon works in our own lives and the vocation more generally; as noted above we are interested in the relationships it establishes in law, the purpose of these, what we would be living apart from the canon and how it differs because of the canon and things like this. Because as hermits our need for legal recourse or canonical consultation is rare at best once we have been admitted to perpetual profession we are ordinarily otherwise completely free to follow our own Rule of Life without worrying about canonical matters. On the other hand, most of us do have an interest in the canon and its normative character when this is being denied or contravened publicly by folks pretending to represent consecrated eremitical life. In any case at least one diocesan hermit here in the US is a canonist working for a diocese so an interest in canon law is at least not antithetical to the eremitical life!

Am I a Law and Order Type?

I don't think I am particularly a "law and order" type, nor are most of the hermits I know. Of course we respect law and see its importance in society and the life of the Church. We are not antinomians or anarchists. Rather, we recognize that c 603 is an historic canon and those I know do feel both honored and obligated to live our lives with a real cognizance of what is finally possible in universal law because of it. There is something really startling and humbling when one realizes one is part of a long-awaited and fought for extension of an ancient tradition into a contemporary situation, and therefore, that one is part of a relative handful of hermits now living a new ecclesial vocation in the name of the Church. Personally, I believe the eremitical vocation has the capacity to redeem (heal and give meaning to) the lives of many people who are isolated by life's circumstances and I feel proprietary about the significance of the canon for this reason as well.

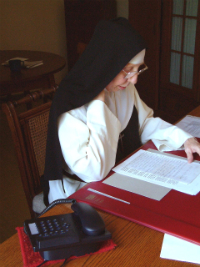

| Sister Ann Marie OCSO signs Solemn Vow Formula |

Misrepresenting Facts to the Vulnerable, A serious Pastoral Matter

Thus, when a person who neither understands canon 603 nor lives under it or in an institute of consecrated life, but still falsely claims to be a "professed religious" and "consecrated Catholic Hermit" while writing, [[Perhaps it is best for all of us, and maybe especially us consecrated Catholic hermits, to not get too caught up in the ins-and-outs of the temporal Catholic rules and laws and the raft of interpretations of those rules and laws]] it strikes me as particularly self-serving and pastorally insensitive. (Neither is it particularly accurate; a single two paragraph canon is hardly a raft of laws nor is c 603 exactly a hotbed of interpretive controversy.) It especially says to me this person has not really understood the reason the Church takes care whom she consecrates and how, whom she professes in this or that vocation and why. In my experience people searching for a way to belong, a way to redeem their own isolation, a way to ensure the meaningfulness of their lives are legion in our world --- and perhaps especially in our culture. They are also more vulnerable to people offering a less difficult or at least more individualistic way to embrace religious life.

We do these persons no favors when we tell them to do whatever they wish, call themselves whatever they wish and never mind about the "temporal laws" of the Church. We do them no favors when we misrepresent facts, misread texts, or treat Canon Law as though it is an option we can ignore while arrogantly calling ourselves "consecrated Catholic hermits" and thus claiming under our own authority a designation only the Church herself can permit us to use. Especially we do these persons no favors by encouraging them to embrace pretense in the name of the God of Truth.

We do these persons no favors when we tell them to do whatever they wish, call themselves whatever they wish and never mind about the "temporal laws" of the Church. We do them no favors when we misrepresent facts, misread texts, or treat Canon Law as though it is an option we can ignore while arrogantly calling ourselves "consecrated Catholic hermits" and thus claiming under our own authority a designation only the Church herself can permit us to use. Especially we do these persons no favors by encouraging them to embrace pretense in the name of the God of Truth.In the end to do that is to betray their deepest longings and treat them as though they are either too unimportant to God to be called to live a significant (meaningful) vocation, or simply too weak to bear the vocation God truly HAS extended to them. This is so because in the Church, standing in law ("status") is always associated with the gift and challenge of responsibility. We do not recognize a person's real dignity nor show genuine respect for them by extending standing (much less allowing them to pretend to standing which is) without commensurate responsibility. In any case, while the institutional Church is not perfect, generally speaking she uses canon law to order and protect her charismatic life, not to stifle it. She uses law to make certain that freedom is not degraded into an irresponsible license. The diocesan hermit does something similar with her Rule and, of course, Canon law, legitimate superiors, and the other mediatory structures and relationships of the Church. These things ordinarily help INSURE the freedom of the hermit, they do not hinder it.

Authentic Freedom:

You see, authentic freedom is the power to be the persons we are called to be in spite of limitations and constraints. In the diocesan hermit vocation, or any vocation to the consecrated state in the Church God calls the person and that call is mediated through the structures of the Church. The charismatic dimension of the Church is always mediated in this way. Catholic hermits are not folks who simply do whatever they want (your friend's more commonly held sense of what it means to be a hermit sounds like more of a stereotype to me); they are persons who do what God wills; Catholic hermits are those who live an eremitical freedom (the will of God) as that is mediated not only in solitude, but in and through the structures of the institutional Church.

In my own experience the Church's canon law here provides some of the necessary structure permitting a person to concern themselves wholeheartedly with prayer, the silence of solitude, and the rest of the eremitical life without concern for whatever the world says, believes, values, etc. Moreover, they do so within the very heart of the Church. That is true whether they do so as canonical (consecrated) or non-canonical (lay). In fact, that is true even when they are fighting for a new way while accepting the current truth of their situation. (The monks who accepted secularization while struggling for something like Canon 603 and living under the protection of Bishop Remi De Roo are exemplars of this kind of creative and risky freedom.) Freedom involves constraints. License is a different matter.

In my own experience the Church's canon law here provides some of the necessary structure permitting a person to concern themselves wholeheartedly with prayer, the silence of solitude, and the rest of the eremitical life without concern for whatever the world says, believes, values, etc. Moreover, they do so within the very heart of the Church. That is true whether they do so as canonical (consecrated) or non-canonical (lay). In fact, that is true even when they are fighting for a new way while accepting the current truth of their situation. (The monks who accepted secularization while struggling for something like Canon 603 and living under the protection of Bishop Remi De Roo are exemplars of this kind of creative and risky freedom.) Freedom involves constraints. License is a different matter.Doing your own thing may pass for freedom, at least for a time, but such persons tend to find they are marginalizing themselves and exacerbating their own sense of unfreedom and meaninglessness. In theological terms they are opting not for the way of the Kingdom and the Life of the Spirit but instead for the way and spirit of the world. The irony is that such persons are therefore more apt than those living fully within the Church's constraints and structures (canonical, liturgical, theological, etc) to be in a destructive bondage, whether that is to insecurity, shame, their own personal failures in life, a fear of meaninglessness, loss, grief, illness, or whatever drives a need to define themselves; whatever creates and grounds this kind of arrogance is not a symptom of freedom but of slavery.

Living Eremitical life inside and Outside the Church:

One could also leave the Church and pursue an eremitical life in open protest to what one might see as the Church's compromises with worldliness (and the way some folks write of Canon 603 and the Church's use of law more generally seems suggest they see these as a terrible compromise with worldliness). I personally think this is unnecessary and misguided; I would not understand it but it is a choice I would respect at the same time for its honesty. What is not okay, what I personally cannot respect, is effectively thumbing one's nose at the Church's clear understanding, law, and sacramental structures while fraudulently calling oneself a "Catholic Hermit" and thus, claiming one is living this life in the very name of the Church. I do think that is a clear misrepresentation of this vocation. Of course, if any person claiming to live eremitical life in the name of the Church is also not really living an exemplary eremitical life but instead is merely trying to validate personal isolation and failure, that, it seems to me, would also be a serious misrepresentation of what the Church understands as the eremitical vocation.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:43 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Canon 603, Catholic Hermits, Diocesan Hermit, Fraudulent Hermits, importance of lay eremitical vocations, lay hermits, public vs private vows, Rule as tool for discernment, Theology of Consecrated Life

05 October 2010

Charism, Counterfeits, and Canon 603

I was drawn to a headline online about the growth of the number of hermits in Britain. The story was a huge disappointment, however, and it was annoying and frustrating to boot. With a subtext of genuine and rightful concern for an aging population in Britain, the reporter told two stories, one of which was the following:

[[Tom Leppard is by no means an ornamental hermit. I interviewed him . . . for my book on English eccentrics. After a brutal convent education, and retired from the armed forces, Tom Leppard moved to London, which he loathed. It made him realise that every time in his life he'd been unhappy people had been involved. So Leppard vowed to become a hermit and moved to a remote part of the Isle of Skye. Before leaving London he had 99.2 per cent of his flesh tattooed with leopard spots, projecting his acute sense of apartness on to his skin.

[[Tom Leppard is by no means an ornamental hermit. I interviewed him . . . for my book on English eccentrics. After a brutal convent education, and retired from the armed forces, Tom Leppard moved to London, which he loathed. It made him realise that every time in his life he'd been unhappy people had been involved. So Leppard vowed to become a hermit and moved to a remote part of the Isle of Skye. Before leaving London he had 99.2 per cent of his flesh tattooed with leopard spots, projecting his acute sense of apartness on to his skin.