[[Dear Sister Laurel, Could you write something about [today's] feast of the Exaltation of the Cross? What is a truly healthy and yet deeply spiritual way to exalt the Cross in our personal lives, and in the world at large (that is, supporting those bearing their crosses while not supporting the evil that often causes the destruction and pain that our brothers and sisters are called to endure due to sinful social structures?]]

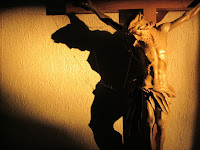

First of all, I think it is helpful to remember the alternative name of this feast, namely, the Triumph of the Cross. For me personally this is a "better" name, and yet, it is a deeply paradoxical one, just like its alternative. We are dealing with the profoundly scandalous way God triumphs over human sin and the powers of evil in our world. It is a feast in which the torture and death of one man is celebrated as the greatest occasion of blessing in human history.

How many times have we heard it suggested that Christians ought not wear crosses around their necks as jewelry any more than they should wear tiny images of electric chairs, medieval racks or other symbols of torture and death? Similarly, how many times has it been said that making jewelry of the cross trivializes what happened there? There is a great deal of truth in these objections, and in similar ones! On the one hand the cross points to the slaughter by torture of hundreds of thousands of people by an oppressive state. More individually it points to the slaughter by torture of an innocent man in order to appease a rowdy religious crowd by an individual of troubled but dishonest conscience, one who put "the supposed greater good" before the innocence of this single victim.

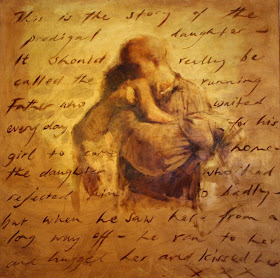

And of course there were collaborators in this slaughter: the religious establishment, disciples who were either too cowardly to stand up for their beliefs, or those who actively betrayed this man who had loved them and called them to a life of greater abundance (and personal risk) than they had ever known before. If we are going to appreciate the triumph of the cross, if we are going to exalt it as Christians do and should, then we cannot forget this aspect of it. Especially we cannot forget that much that happened here was not the will of God, nor that generally the perpetrators were not cooperating with that will! The cross was the triumph of God over sin and sinful godless death, but it was also a sinful and godless human (and societal!) act of murder by torture. (In fact one could argue it was a true divine triumph only because it was also these all-too-human things.) Both aspects exist in tension with each other, as they do in all of God's victories in our world. It is this tension our jewelry and other crucifixes embody: they are miniature instruments of torture, yes, but also symbols of God's ultimate triumph over the powers of sin and death with which humans are so intimately entangled and complicit.

In our own lives there are crosses, burdens which are the result of societal and personal sin which we must bear responsibly and creatively. That means not only that we cannot shirk them, but also that we bear them with all the assistance that God puts into our hands. Especially it means allowing God to assist us in the carrying of this cross. To really exalt the cross of Christ is to honor all that God did with and made of the very worst that human beings could do to another human being. To exult in our own personal crosses means, at the very least, to allow God to transform them with his presence. That is the way we truly exalt the Cross: we allow it to become the way in which God enters our lives, the passion that breaks us open, makes us completely vulnerable, and urges us to embrace or let God embrace us in a way which comforts, sustains, and even transfigures the whole face of our lives.

If we are able to do this, then the Cross does indeed triumph. Suffering does not. Pain does not. Neither will our lives be defined in terms of these things despite their very real presence. What I think needs to be especially clear is that the exaltation of the cross has to do with what was made possible in light of the combination of awful and humanly engineered torment, and the grace of God. Sin abounded but grace abounded all the more. Does this mean we invite suffering so that "grace may abound all the more?" Well, Paul's clear answer to that question was, "By no means!" How about tolerating suffering when we can do something about it? What about remaining in an abusive relationship, or refusing medical treatment which would ease mental and physical pain, for instance? Do we treat these as crosses we must bear? Do we allow ourselves to become complicit in the abuse or the destructive effects of pain and physical or mental illness? I think the general answer is no, of course not.

That means we must look for ways to allow God's grace to triumph, while the triumph of grace always results in greater human freedom and authentic functioning. Discerning what is necessary and what will really be an exaltation of the cross in our own lives means determining and acting on the ways freedom from bondage and more authentic humanity can be achieved. Ordinarily this will mean medical treatment; or it will mean moving out of the abusive situation. In all cases it means remaining open to and dependent upon God and to what he desires for our lives in spite of the limitations and suffering inherent in them. This is what Jesus did, and what made his cross salvific. This openness and responsiveness to God and what he will do with our lives is, as I have said many times before, what the Scriptures called obedience. Let me be clear: the will of God in any situation is that we remain open to him and that authentic humanity be achieved. We must do whatever it is that allows us to not close ourselves off to God, and to remain open to growth as human. If our pain dehumanizes, then we must act as we can to change that. If our lives cease to reflect the grace of God (and this means, "it fails to be a joyfilled, free, fruitful, loving, genuinely human life") then we must do what it takes to allow grace to triumph.

The same is true in society more generally. We must act in ways which open others to the grace of God. Yes, suffering does this, but this hardly means we simply tell people to pray, grin, and bear it ---- much less allow the oppressive structures to stay in place! As the gospels tell us, "the poor you will always have with you" but this hardly means doing nothing to relieve poverty! Similarly we will always have suffering with us on this side of death, and especially the suffering that comes when human beings institutionalize their own sinful drives and actions. What is essential is that the Cross of Christ is exalted, that the Cross of Christ triumphs in our lives and society, not simply that individual crosses remain or that we exalt them (especially when they are the result of human engineering and sin)! And, as I have written before, to allow Christ's Cross to triumph is to allow the grace of God to transform all the dark and meaningless places with his presence, light and love. It is ONLY in this way that we truly "make up for what is lacking in the passion of Christ."

The paradox in today's feast is that the exaltation of the Cross implies suffering, and stresses that the Cross of Christ empowers the ability to suffer well, but at the same time points to a freedom the world cannot grant --- a freedom in which we both transcend and transform suffering because of a victory Christ has won over the powers of sin and death which are built right into our lives and in the structures of this world. Thus, we cannot ever collude with the powers of this world; we must always be sure we are acting in complicity with the grace of God instead. Sometimes this means accepting the suffering that comes our way (or encouraging and supporting others in doing so of course), but never for its own sake. If our (or their) suffering does not result in greater human authenticity, greater freedom from bondage, greater joy and true peace, then it is not suffering which exalts the Cross of Christ. If it does not in some way transform and subvert the structures of this world which oppress and destroy, then it does not express the triumph of Jesus' Cross, nor are we really participating in that Cross in embracing our own.