19 June 2014

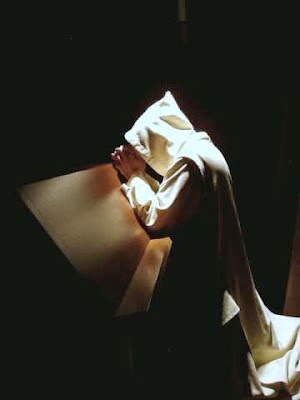

A Contemplative Moment: The Inner Self

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:43 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Thomas Merton, True and False selves, William Shannon

17 June 2014

On Thinking About the True or Inner Self

[[Dear Sister Laurel, you referred recently to the "true self" and I have seen references to this in other writers dealing with spirituality. Keating and others in the Centering Prayer movement refer to this and I have the sense it is a monastic way of speaking. My problem is I have never found a good presentation of what it is or is not. I know that the false self is the ego self but is the true self our soul or our heart or what exactly is it? Is there someone I can read on this?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, you referred recently to the "true self" and I have seen references to this in other writers dealing with spirituality. Keating and others in the Centering Prayer movement refer to this and I have the sense it is a monastic way of speaking. My problem is I have never found a good presentation of what it is or is not. I know that the false self is the ego self but is the true self our soul or our heart or what exactly is it? Is there someone I can read on this?]]

This is a great question because defining the true self is difficult and treating it as a kind of "little person," homunculus, or piece of ourselves somewhere inside us is a real danger. I tend to think of my true self as that self God envisions and calls me to be. If I need something a little more tangible (or that at least feels more tangible!) I think of it as the Name by which God knows and calls me. It is as much potential as it is real(ized).This emphatically does not mean that there is a kind of template, much less an invisible person hidden deep within us. The true self is not our soul nor perhaps even our "heart" (though as I understand "heart" the two are profoundly related). In any case, the true self is a dialogical event which comes to be in the very moment of obedient response to the Word and Summons of God. In a sense when we speak of the true self we are talking about a reality in the mind or heart of God as well as an event which is the result and embodiment of his love as it is received at any given moment in our own lives. It is that person we are when we are most truly alive, most truly ourselves, most truly living from and in God. Merton refers to it as "a spontaneity," and finds it in every deeply spiritual experience, "whether religious, moral, or even artistic." In The Inner Experience he writes:

[[The inner self [another term for the true self] is not part of our being, like a motor in a car. It is our entire substantial reality itself, on its highest and most existential level. It is like life, and it is life: it is our spiritual life when it is most alive. It is the life by which everything else in us lives and moves. . . .The inner self is as secret as God and, like Him, it evades every concept that tries to seize hold of it with full possession. It is a life that cannot be held and studied as object, because it is not "a thing." It is not reached and coaxed forth from hiding by any process under the sun, including meditation. All that we can do with any spiritual discipline is produce within ourselves something of the silence. the humility, the detachment, the purity of heart, and the indifference which are required if the inner self is to make some shy, unpredictable manifestation of his (its) presence.]]

[[The inner self [another term for the true self] is not part of our being, like a motor in a car. It is our entire substantial reality itself, on its highest and most existential level. It is like life, and it is life: it is our spiritual life when it is most alive. It is the life by which everything else in us lives and moves. . . .The inner self is as secret as God and, like Him, it evades every concept that tries to seize hold of it with full possession. It is a life that cannot be held and studied as object, because it is not "a thing." It is not reached and coaxed forth from hiding by any process under the sun, including meditation. All that we can do with any spiritual discipline is produce within ourselves something of the silence. the humility, the detachment, the purity of heart, and the indifference which are required if the inner self is to make some shy, unpredictable manifestation of his (its) presence.]]

One of the difficulties in speaking of the true self is our failure to understand it in terms of its dynamic and dialogical quality. We think of it as "already there" waiting passively --- apart in some sense from active participation in our relationship with God, apart, that is, from our participation in God's ongoing and eternal creative activity. But this, I think, is not the case. The true self is what exists to the extent and at the very moment we are in dialogue with God. It is that Self which is actively involved in the I-Thou relationship with God. In a sense it IS this I-Thou relationship embodied in space and time, this God-speaking-human being-hearkening Event we know as "incarnated Word". I have written before that God is eternal because God is always new (kainotes) and is eternal only to the extent that God is always new. I think we have to understand that the true self has a similar kind of existence. Merton's use of the term "a spontaneity" is especially apt --- but we must understand that because the true self always and only exists in and from God there is an eternity to it as well. Still, this eternity is not so much one of persistence (which is a temporal reality) as it is of an eternal now --- a moment by moment giveness and receivedness. My own use of the term Event is an attempt to do justice to the paradox of newness (spontaneity) and eternity in God and in myself as well.

Similarly, I speak and think of true self in relation to the Name by which God calls me because it helps me remember that the true self is not a template or pattern of characteristics I must somehow embody or live up to. It wholly transcends this just as any Name does. I think it also allows us to speak here of the secret name by which God knows and calls us because often (always?) this is very different from the more usual name by which the whole world knows us or, even more emphatically so from the name we try to make for ourselves. At the same time focusing on Name immediately causes me to understand that existence is a gift I cannot give myself and that the true self is the result of God's own speech as hearkened to by the me it makes more real.

Similarly, I speak and think of true self in relation to the Name by which God calls me because it helps me remember that the true self is not a template or pattern of characteristics I must somehow embody or live up to. It wholly transcends this just as any Name does. I think it also allows us to speak here of the secret name by which God knows and calls us because often (always?) this is very different from the more usual name by which the whole world knows us or, even more emphatically so from the name we try to make for ourselves. At the same time focusing on Name immediately causes me to understand that existence is a gift I cannot give myself and that the true self is the result of God's own speech as hearkened to by the me it makes more real.

Finally, Name points to the embodiment of true freedom we are called to be and become. There is no pre-conceived "person" or "plan" attached to a name. Instead the bestowal of a name gives us a dignity, a capacity and even a commission which we ourselves will "fill" with content --- and yet, above all, that content is who we are in our relatedness with God and all that is from and of God. If one were to try to capture or define the content of a personal Name one would fail as surely as they would fail trying to capture a living brook or flowing river in a bucket. So too with the true self that, like Godself, is really more verb than noun. All of these things are sort of the counterpart to apophatic ways of knowing God. We know God only to the extent we are known by God and any worthwhile attempt to speak positively about the reality of God must center on saying clearly what God is not. Where finally we come to know God as (an) ultimate freedom so too do we come to know the true self as a contingent freedom --- that is, ourselves as we truly (and "spontaneously") exist in and from God.

Addendum:

One other way the true or inner self is often referred to is with the term "deep self." It is not a term I usually use personally but I was reminded of it and reflected on how it might illustrate what I wrote yesterday. Theologians like Paul Tillich (who was influential in Merton's own thought) refer to God and too, to the literally spiritual as the depth dimension of all reality. When, with Tillich, we refer to God as the ground of being and meaning we are referring to this same depth dimension -- a dimension which grounds and can penetrate and take hold of every aspect of our existences, a dimension of depth which is manifest in our religious, moral, intellectual, and aesthetic lives whenever we are grasped by meaning, truth, beauty, or future, etc --- that is, whenever we are grasped by (an ultimate) concern expressed by or through these.

The depth dimension in all of these human endeavors or functions is their participation in ultimacy and the transcendent. My sense is the "deep self" is that self which is grasped by this depth dimension whenever this occurs; this means it is real in the event of our everyday selves being grasped, shaken, and transformed by depth or Spirit. (Remember that because of Jesus' Ascension the Holy Spirit is also the Spirit of authentic humanity!) It is, in other words, all of ourselves taken hold of and shaken by ultimacy (and thus, by an ultimate concern), whether that occurs (as Merton pointed out as well) in the intellectual, the moral, religious, or the artistic realms of our lives. If this seems a bit too abstract or the language feels too foreign, notice how it continues the theme of spontaneity or reprises comments on the event nature of the true self. Because for Tillich faith is "the state of being grasped by an ultimate concern" the true self can be called that self which is taken hold of by faith -- not as believing in x or y, but in the sense of allowing ourselves to trustingly fall into the hands of the living God who, at that moment, makes all things new.

The depth dimension in all of these human endeavors or functions is their participation in ultimacy and the transcendent. My sense is the "deep self" is that self which is grasped by this depth dimension whenever this occurs; this means it is real in the event of our everyday selves being grasped, shaken, and transformed by depth or Spirit. (Remember that because of Jesus' Ascension the Holy Spirit is also the Spirit of authentic humanity!) It is, in other words, all of ourselves taken hold of and shaken by ultimacy (and thus, by an ultimate concern), whether that occurs (as Merton pointed out as well) in the intellectual, the moral, religious, or the artistic realms of our lives. If this seems a bit too abstract or the language feels too foreign, notice how it continues the theme of spontaneity or reprises comments on the event nature of the true self. Because for Tillich faith is "the state of being grasped by an ultimate concern" the true self can be called that self which is taken hold of by faith -- not as believing in x or y, but in the sense of allowing ourselves to trustingly fall into the hands of the living God who, at that moment, makes all things new.

For a very accessible introduction to this notion of "depth dimension" cf Paul Tillich's sermon, "The Depth of Existence" in his book, The Shaking of the Foundations. Also helpful would be his sermon, "Our Ultimate Concern" in The New Being.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

3:28 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: apophatic tradition, Paul Tillich, the power of name., The Shaking of the Foundations, Thomas Merton, True and False selves

12 June 2014

Merton, TS Elliot, The Apophatic Way and My Own Contemplative Life

Dear Sister, I like the posts you have put up with the picture of the monk and the quotes from Merton and T.S. Elliot. I hope you continue these. Is Merton a favorite writer and spiritual teacher for you? I ask because some people have written that he went kind of awry or was "off" in his later years and was discredited as a Catholic monk. I don't mean you shouldn't read him but I wondered why you liked him and if you thought that was true.]]

Dear Sister, I like the posts you have put up with the picture of the monk and the quotes from Merton and T.S. Elliot. I hope you continue these. Is Merton a favorite writer and spiritual teacher for you? I ask because some people have written that he went kind of awry or was "off" in his later years and was discredited as a Catholic monk. I don't mean you shouldn't read him but I wondered why you liked him and if you thought that was true.]]

Hi there. Thanks for your comments on the posts. I do plan to continue these. Not only do I love the picture -- which for me sums up so much of the eremitical life -- but I think these posts provide a way of giving a small but significant taste of various authors on the contemplative journey from time to time. When I first thought of combining the picture with a single quote I was thinking that visually and otherwise it would present as a kind of contemplative moment within the blog itself; I thought that might be really attractive to folks who come here. I haven't decided how often I want to put these up -- not TOO frequently of course --- and I think I also need to title them similarly so they stand out as a regular feature of the blog, but those logistical matters aside, yes I will continue to put them up.

As for Thomas Merton, yes, he is a favorite writer and spiritual teacher (or mentor) for me though until very recently it had been some time since I had actually read him. I was saying to a friend earlier today that I have just recently come back to Merton and am beginning to reread him with new eyes. I first picked up his stuff in the late 1960's or early 1970's. Later, in the 1980's I read some of his work on eremitical life. Along with Merton's own stuff I am looking again at the work of William Shannon. The latter's revision of The Dark Path (his new book is called Thomas Merton's Paradise Journey) is really exciting because in it I am reading again about something I once felt called to and with which I resonated to some limited degree, but now recognize as profoundly descriptive of my own spiritual journey and contemplative experience. You see, Merton's approach to contemplation and my own are the same (which is hardly surprising!); we both were called to the "apophatic" (a-poh-FAT-ic) tradition or way --- the way of darkness and denial. (It comes from the Greek word apophasis (uh-POF-uh-sis) which means negation or denial, ("God is not. . ."). It's opposite is the kataphatic or affirmative way (kataphasis [keh-TAF-uh-sis] means affirmation); it is a way of doing theology which proceeds by way of analogy and makes affirmations about God both in terms of similarity ("God is like. . .") and even greater dissimilarity ("but God is even more unlike . . ."). It does not, by definition, penetrate to the deepest essence or heart of God)

Apophatic Tradition in Contemplation

Apophatic contemplation, which is a way built on "experiencing" God directly, thrives on paradox and I have been turned on by paradox and especially by the paradoxes of Christianity from the moment my first major professor explained the difference between the way Greek thought tends to proceed and the way Biblical thought works. (The first moves from thesis to antithesis and then comes to rest in a synthesis which often is a kind of golden mean. Biblical thought, on the other hand, is at home with paradox --- a kind of both/and approach to thought and reality which often says things like "Dive into the emptiness and there you will find real fullness," "In losing yourself you will find yourself," "God's mercy IS his justice", and so forth.) For the contemplative knows that even though many of us are driven to write many words about prayer, spirituality, or theology, none of them even comes close to describing God or the experience (or non-experience!) of prayer. At the same time we know that the tensions of paradox come closest to conveying the truth about God and God's dealings with us --- though many would call them senseless babblings. Thus God is a light we only perceive as darkness or a darkness which illuminates, an emptiness which is fullness, the nothing which is all, so that faith and prayer involve a vulnerable leap (which we both must make and actually cannot make ourselves!) into a void in which we find (or rather are found by) total security. You get the idea I think.

Of course the really big name in the apophatic way is John of the Cross (The Ascent of Mount Carmel, The Living Flame of Love, ). Meanwhile, T.S. Elliot may also have been "schooled" in the apophatic tradition because in true apophatic style he speaks of coming again to the place where he began and knowing that place for the first time. In Little Gidding V Elliot piles paradox upon paradox but he begins with the following one: [[We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.]] This really is the experience of contemplative prayer, the experience of seeking and exploring that which in some sense we know and desire profoundly as our source and starting place only to come to "know the place for the first time." Merton comes at it from the other way around and says it this way, [[[Contemplation] strikes us at once as utterly new and strangely familiar. . .Although we had an entirely different notion of what it would be like, it turns out to be just what we seem to have known all along that it ought to be. . .We enter a region which we had never even suspected, and yet, it is this new world which seems familiar and obvious.]] Seeds of Contemplation pp 144-145

Of course the really big name in the apophatic way is John of the Cross (The Ascent of Mount Carmel, The Living Flame of Love, ). Meanwhile, T.S. Elliot may also have been "schooled" in the apophatic tradition because in true apophatic style he speaks of coming again to the place where he began and knowing that place for the first time. In Little Gidding V Elliot piles paradox upon paradox but he begins with the following one: [[We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.]] This really is the experience of contemplative prayer, the experience of seeking and exploring that which in some sense we know and desire profoundly as our source and starting place only to come to "know the place for the first time." Merton comes at it from the other way around and says it this way, [[[Contemplation] strikes us at once as utterly new and strangely familiar. . .Although we had an entirely different notion of what it would be like, it turns out to be just what we seem to have known all along that it ought to be. . .We enter a region which we had never even suspected, and yet, it is this new world which seems familiar and obvious.]] Seeds of Contemplation pp 144-145Thomas Merton, A Brief Evaluation:

All of which brings me back to Thomas Merton and your questions. (Really!!) You see, this is the nature of my own contemplative experience and for that reason I know Thomas Merton to have been the real deal. So much of what he writes resonates with me and my own experience in prayer, but also with the "greats" like John of the Cross, the author of the Cloud of Unknowing, many of the Greek Fathers, et al. But besides that, I think I largely owe him for my eremitical vocation. You see when I read canon 603 for the first time it was intriguing to me personally and suggested a way all the dimensions of my life could be rendered coherent (that is, made to hold together in meaningful whole). However, I also doubted such a vocation could be anything but selfish. (Contemplative life struck me that way; eremitical life was far worse --- it seemed a kind of epitome or summit of selfishness!) I then read Dom Jean LeClercq's Alone With God which intrigued me; I liked it very much though I had no idea the Camaldolese existed. Still, I had doubts about the value of the life. Then I read Merton's Contemplation in a World of Action. As I have written here before, it electrified me because it showed eremitical life as valid and more, as a significant gift of God to the Church and world. Later I read his "Notes on a Philosophy of Solitude" in Disputed Questions and that became a new favorite -- but by that time I was already a hermit and had been for more than twenty years.

Some suggest he was not a true monk or that he had confessed upon walking into a library with shelves of his books that much of it was crap (I think he said B.S.). I have already written about those things in this blog and will link you to it here: Defending Thomas Merton . Bear in mind that for the apophatic contemplative words ALWAYS not only fall short of but also betray God. We are nonetheless compelled to write about God and prayer but with an awareness that when what we write is compared to the God who grasps us in prayer, the judgment must always be what it was for Thomas Merton, Thomas Aquinas and so many others: this is as straw, it is a load of refuse, BS, etc. Further our work is always also our very own and reflects not just our virtue, our knowledge, and our union with God but our limitations and even our sinfulness or estrangement from that same God and our truest selves. Thus when Merton looked upon the newly published Seeds of Contemplation, for instance, he remarked, "Every book I write is a mirror of my own character and conscience. I always open the final printed job with the faint hope of finding myself agreeable and I never do" He goes on to say both sincerely and perhaps with more than a little contemplative irony (or all-too-human hyperbole), "There is nothing to be proud of in this one either. : ."

Some suggest he was not a true monk or that he had confessed upon walking into a library with shelves of his books that much of it was crap (I think he said B.S.). I have already written about those things in this blog and will link you to it here: Defending Thomas Merton . Bear in mind that for the apophatic contemplative words ALWAYS not only fall short of but also betray God. We are nonetheless compelled to write about God and prayer but with an awareness that when what we write is compared to the God who grasps us in prayer, the judgment must always be what it was for Thomas Merton, Thomas Aquinas and so many others: this is as straw, it is a load of refuse, BS, etc. Further our work is always also our very own and reflects not just our virtue, our knowledge, and our union with God but our limitations and even our sinfulness or estrangement from that same God and our truest selves. Thus when Merton looked upon the newly published Seeds of Contemplation, for instance, he remarked, "Every book I write is a mirror of my own character and conscience. I always open the final printed job with the faint hope of finding myself agreeable and I never do" He goes on to say both sincerely and perhaps with more than a little contemplative irony (or all-too-human hyperbole), "There is nothing to be proud of in this one either. : ."Meanwhile, as someone associated with the Camaldolese as an oblate, I know that many Christian Contemplatives read, study, and regularly meet and discuss with contemplatives of other religious traditions. Some of my Camaldolese brothers and sisters in particular are specialists in other contemplative traditions and the New Camaldoli hermitage hosts inter-religious meetings of such contemplatives regularly though not frequently. We (contemplatives from various religious traditions) have a lot in common precisely because the God we meet transcends words and descriptions --- and also the limits of our own religious traditions. (Sometimes our own clinging to these limits represents what Mary Magdalene did with the Risen Christ and we need to remember that while we are to honor these traditions appropriately for all they truly reveal/mediate to us, they must not cause us to cling to a yet-unascended Jesus nor to limit the reach of the Holy Spirit.)

Though aware of all this (and paradoxically too, because of it) Merton never ceased to be a Christian and a Cistercian Monk. Because his own life reflected the paradoxes and tensions of the contemplative who is drawn beyond more usual borders and boundaries I understand why what he wrote was uncomfortable for some of his confreres and others. Of course, I also know he was a flawed human being; his unacceptable behavior with the nurse he met during his stay in hospital was unjustifiable -- though he tried pretty hard (and pitifully) to do this in what I read of his last journal. Still, my own judgment on Merton is favorable. He was and remained a Catholic Christian, Trappist Monk, and true contemplative who was also a contemporary hermit and a fine writer. I am grateful to God for his life and more than a little sorry for his premature death because I would have liked to have known him.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:03 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: apophatic tradition, contemplation, John of the Cross, kataphatic tradition, LitttleGidding V, Ruth Burrows OCD, Sister Rachel OCD, The Contemplative Experience, Thomas Merton, TS Elliot

28 May 2014

A Contemplative Moment: The Silence of Solitude

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:26 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A Contemplative Moment, silence of solitude, solitude, Thomas Merton

25 May 2014

Fraudulent "Catholic Hermits": Is it a Big Problem?

[[[Hi Sister Laurel, is the problem of fraudulent hermits a big one? Do many people claim to be Catholic hermits when they are not? I am asking because you have written recently about the normative character of c 603 vocations and some who pretend to be Catholic hermits. Was the Church concerned with frauds and people like that when they decided to create this canon?]] (redacted)

No, on the whole this is not really a huge problem, or at least it was not a problem when I first started the process of becoming a diocesan hermit. I don't think it is that much of a problem even now though I do hear (or know firsthand) of cases here and there of folks who pull on a habit (or the gaunt visage and behavior of a supposed "mystic"), don the title "Catholic hermit" and then turn up on the doorstep of a parish expecting to be recognized and known in this way. There was also a website a couple of years ago using the names of legitimate (canonical) diocesan hermits to get money through paypal without the knowledge of these same diocesan hermits. Part of the problem is that the authentic vocation is so rare and little-understood in absolute terms that a handful of counterfeits or frauds can have a greater impact relatively speaking. Those disedifying and fraudulent cases aside, however, the origins of the canon are actually pretty inspiring and had nothing to do with frauds or counterfeits. To reprise that here:

No, on the whole this is not really a huge problem, or at least it was not a problem when I first started the process of becoming a diocesan hermit. I don't think it is that much of a problem even now though I do hear (or know firsthand) of cases here and there of folks who pull on a habit (or the gaunt visage and behavior of a supposed "mystic"), don the title "Catholic hermit" and then turn up on the doorstep of a parish expecting to be recognized and known in this way. There was also a website a couple of years ago using the names of legitimate (canonical) diocesan hermits to get money through paypal without the knowledge of these same diocesan hermits. Part of the problem is that the authentic vocation is so rare and little-understood in absolute terms that a handful of counterfeits or frauds can have a greater impact relatively speaking. Those disedifying and fraudulent cases aside, however, the origins of the canon are actually pretty inspiring and had nothing to do with frauds or counterfeits. To reprise that here:

A number of monks, long solemnly professed, had grown in their vocations to a call to solitude (traditionally this is considered the summit of monastic life); unfortunately, their monasteries did not have anything in their own proper law that accommodated such a calling. Their constitutions and Rule were geared to community life and though this also meant a significant degree of solitude, it did NOT mean eremitical solitude. Consequently these monks had to either give up their sense that they were called to eremitical life or they had to leave their monastic vows, be secularized, and try to live as hermits apart from their monastic lives and vows. Eventually, about a dozen of these hermits came together under the leadership of Dom Jacques Winandy and the aegis of Bishop Remi De Roo in British Columbia (he became their "Bishop Protector"); this gave him time to come to know the contemporary eremitical vocation and to esteem it and these hermits rather highly.

When Vatican II was in session Bishop de Roo, one of the youngest Bishops present, gave a written intervention asking that the hermit life be recognized in law as a state of perfection and the possibility of public profession and consecration for contemporary hermits made a reality. The grounds provided in Bishop Remi's intervention were all positive and reflect today part of the informal vision the Church has of this vocation. (You will find them listed in this post, Followup on the Visibility of the c 603 Vocation.) Nothing happened directly at the Council (even Perfectae Caritatis did not mention hermits), but VII did require the revision of the Code of Canon Law in order to accommodate the spirit embraced by the Council as well as other substantive changes it made necessary; when this revised code eventually came out in October of 1983 it included c. 603 which defined the Church's vision of eremitical life generally and, for the first time ever in universal law, provided a legal framework for the public profession and consecration of those hermits who desired and felt called to live an ecclesial eremitical vocation.

So you see, the Church was asked at the highest level by a Bishop with significant experience with about a dozen hermits living in a laura in BC to codify this life so that it: 1) was formally recognized as a gift of the Holy Spirit, and 2) so that others seeking to live such a life would not have the significant difficulties that these original dozen hermits did because there was no provision in either Canon Law nor in their congregations' proper laws.

So you see, the Church was asked at the highest level by a Bishop with significant experience with about a dozen hermits living in a laura in BC to codify this life so that it: 1) was formally recognized as a gift of the Holy Spirit, and 2) so that others seeking to live such a life would not have the significant difficulties that these original dozen hermits did because there was no provision in either Canon Law nor in their congregations' proper laws.

The majority of diocesan hermits (i.e., hermits professed in the hands of a diocesan Bishop) have tended to have a background in religious life; it is only in the past years that more individuals without such formation and background have sought to become diocesan hermits. This has left a bit of a hole in terms of writing about the vocation; it has meant not only that the nuts and bolts issues of writing a Rule of life, understanding the vows, and learning to pray in all the ways religious routinely pray have needed to be discussed somewhere publicly, but that the problems of the meaning and significance of the terms, "ecclesial vocation", "Catholic hermit," etc. as well as basic approaches to formation, the central elements of the canon, and so forth have needed to be clarified for lay persons, some diocesan hermits, and even for those chanceries without much experience of this vocation.

My Own Interest in the Ecclesiality of the C 603 vocation:

One of the least spoken of non-negotiable elements of canon 603 is that this is a life lived for the praise of God and the sake and indeed, the salvation of others. The usual focus in most discussions and in discernment as well tends to be on the silence of solitude, assiduous prayer and penance, and stricter separation from the world, as well as on the content of the vows, but I have not heard many talking about or centering attention on the phrase, "for the praise of God and the salvation of the world." However, this element very clearly signals that this vocation is not a selfish one and is not meant only for the well-being of the hermit. It also, I believe, is integral to the notion that this is an ecclesial vocation with defined rights and obligations lived in dialogue with the contemporary situation.

To say this vocation has a normative shape and definition is also to say that not everything called eremitism in human history glorifies God. Further, calling attention to the fact that this is a normative or ecclesial vocation is just the flip side of pointing out that this is a gift of the Holy Spirit meant for the well-being of all who come to know it (as well as those who do not). I am keen that diocesan hermits embrace this element of their lives fully --- and certainly I also desire that chanceries understand that the discernment of vocations cannot occur adequately unless the charism of the vocation is truly understood and esteemed. The ecclesial nature of the vocation is part of this charism as is the prophetic witness I spoke of earlier. By far this is the larger issue driving my writing about the normative and ecclesial nature of this vocation or continuing to point out the significance of canonical standing than the existence of a few counterfeit "Catholic hermits".

Letting Go of Impersonation: the Real Issue for all of us

As I consider this then, I suppose the problem of frauds (or counterfeits) is certainly more real than when I first sought admission to profession under canon 603 (the canon was brand new then and few knew about it), but for most of us diocesan hermits the real issue is our own integrity in living this life and allowing the Church to discern and celebrate other instances of it rather than dealing with the sorry pretense and insecurity which seems to drive some to claim titles to which they have no right. What serious debate takes place does so on this level, not on more trivial ones. The question of fraud is an important one for the hermit both personally and ecclesially because as Thomas Merton reminds us all: [[The . . .hermit has as his first duty, to live happily without affectation in his solitude. He owes this not only to himself but to his community [by extension diocesan hermits would say parish, diocese, or Church] that has gone so far as to give him a chance to live it out. . . . this is the chief obligation of the . . .hermit because, as I said above, it can restore to others their faith in certain latent possibilities of nature and of grace.]] (Emphasis added, Contemplation in a World of Action, p. 242)

In any case, as Thomas Merton also knew very well, some of those who are frauds (and I am emphatically NOT speaking here of lay hermits who identify themselves as such) might well embrace true solitude in the midst of their pretense; if they do, if they find they have a true eremitical vocation, it will only be by discovering themselves getting rid of any pretense or impersonation as well as finding their craziness or eccentricity dropping away. After all, as Merton also noted, one cannot ultimately remain crazy in the desert (that is, in the absence of others and presence of God in solitude) for it takes other people to make and allow us to be crazy. He writes: [[To be really mad you need other people. When you are by yourself you soon get tired of your craziness. It is too exhausting. It does not fit in with the eminent sanity of trees, birds, water, sky. You have to shut up and go about the business of living. The silence of the woods forces you to make a decision which the tensions and artificialities of society help you to evade forever. Do you want to be yourself or don't you?]] (Idem, 245, emphasis added)

You see, the simple truth which makes the existence of fraudulent hermits not only intriguing but also tremendously sad and ironic -- and which is also the universal truth we all must discover for ourselves -- is that alone with God we find and embrace our true selves. If we must continue in our pretense or various forms of impersonation then something is seriously askew with our solitude and therefore too, with our relationship with God (and vice versa).

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:15 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: becoming a Catholic Hermit, Bishop Remi De Roo, Canon 603 - history, Canonical Status, Charism of the Diocesan Hermit, Ecclesial Vocations, For the Salvation of the World, Thomas Merton, Validation vs redemption of Isolation

10 September 2012

Contemplative Prayer, a Waste of Time?

Occasionally folks write things meant to provoke reactions rather than solicit actual responses. This is especially true when folks write to me re this blog and with religious listserves. I sometimes think folks do this to deal with their own demons with regard to religion, but sometimes the antagonism is simply too much and those demons are not exorcised. Recently someone wrote the following and in it refers to Thomas Merton's contemplative practice as an inefficient way of merely "clearing one's mind" and a waste of time: [[ Thomas Merton, like other monks, was known to sit perfectly still for over an hour just trying to contemplate or meditate on God. If you try sitting still and not even moving your neck for an hour, you will see it is very hard. Now that I look back on those moments of contemplation, it seems like a waste of his time. Maybe he felt it helped clear his mind, but surely he could have cleared his mind without adopting such a rigid pose. At the bottom line, do we think any person can get closer to God and understand God better from spending hours each week in complete silence waiting to hear something from God?]]

I actually think that the questions implied here are good ones and perhaps I err often here by assuming people know more about contemplative prayer than they do. I know that eremitical life is not understood by most folks but I forget that for many in our world time spent in prayer, especially contemplative prayer, can truly seem like a terrible waste of time. I have several friends who call themselves atheists --- though they differ on the definition of that and (during one conversation we had together) were quite surprised to hear that consistent atheism actually denies the reality of meaning, or that there are some definitions of God they reject which mainline first-rate theologians would also reject as caricatures. What these folks (and the person who wrote about contemplation as he did above) all seem to have in common is a naivete about really basic things --- in this case the purpose and nature of contemplative prayer. My response to these comments would be:

Sitting in silence for an hour is not hard or a waste of time --- no more than sitting silently with a friend for an hour is difficult or a waste of time, that is. The accent is not on not moving, however; it really is not too difficult to sit in a completely relaxed but alert way for an hour. In Christian contemplation small movements occur but the general posture does not change much. Unlike in some forms of Zen sitting, a Christian moves (and is completely free to move) various muscles or muscle groups in order to relieve remaining stress, ease occasional pain, etc. The purpose of sitting in contemplative prayer is not to learn to ignore one's body or experiences of discomfort or pain, but to enable one to listen to what is happening within oneself where God is ALWAYS speaking.

Thus, this kind of sitting is not inflexible or rigid, nor does it foster an insensibility to what one experiences but instead is relaxed and natural, thus fostering attention to one's inner life. It is this relaxed and natural way of sitting that makes it easy to maintain. In my own life and in monasteries where I go on retreat it is natural to sit for an hour in the mornings. At the monastery it is also not uncommon to do a period of "walking meditation" after 40 minutes or so of sitting, and then to resettle in one's original sitting position. This is helpful for guests and also for older Sisters who might need to move a bit. Again, the accent is not on immobility but on presence and prayer.

Neither does one contemplate by spending "hours waiting to hear something from God" --- as though one is expecting a kind of spiritual telegram or as though God is not always speaking, always calling, always acting to reveal himself if only we would learn to listen. Instead one sits in silence and opens one's heart to the reality of God's presence and voice. Whether one hears anything telegram-like, has any striking insights or not, the purpose is to give oneself wholly to God, to allow him the space, time, and freedom to love one and reveal himself in any way whatsoever. One learns to "hear" God in the silence of one's heart --- the place where, by definition, God "bears witness to himself". Such periods, far from being a waste of time, are deeply humanizing. That is certainly what Merton found them to be and what all the monastics and contemplatives I know regularly find.

The capacity to listen and respond is fundamental to human being. The capacity to listen to one's own heart as the fount from which life is continually bubbling up and one's own call or invitation to be is issued moment by moment, is something we all need to develop. As I wrote earlier, the capacity to listen and respond (hearken) in this way is thought to be the most basic dynamic of human life and it is from this capacity that our own capacity to hearken to others comes. To cut oneself off from such hearkening is a symptom of relative inhumanity. As we learn to listen, however, we draw closer to ourselves --- our truest, most original selves --- and to the God who grounds our being (for these two exist as a communion). As we do this, we become more capable of giving ourselves to others, to living from this deep and more original self, and to calling others to do the same.

Our world does not actually foster this kind of deep, humanizing listening. Instead it is all about constant noise, continuous stimuli, repeated escape from introspection, silence, solitude, or the threat of boredom. Our resulting relationships reflect this and the incapacity it fosters. Consider the friends who stand near one another and text each other rather than actually speaking and listening profoundly to one another, or the couples that go out for coffee and then spend time texting other friends who are not there. Consider the homes in which the TV, computer, iPod, stereo, etc are constant accompaniments --- even to family meals or conversations. These are the tip of a very large and destructive iceberg, I think. Contemplatives practice sitting in silence because we are all called more fundamentally to a different and far more profound listening, dialogue, and communion than we are used to considering, much less pursuing.

It is not that contemplatives expect to learn something new about God, or that we expect to hear him speak to us in some divine equivalent of a voice mail or text message --- though occasionally something like that might actually happen; it is that we wish to allow God to take hold of us completely, that we recognize our silence gives him space to create, heal, and recreate us as persons capable of real listening --- and from there, gives him some of the space needed to heal and recreate the entire world. I would say this is hardly a waste of time.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

9:22 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Authentic humanity, contemplation as engagement, obedience, Thomas Merton

06 February 2009

Confusions regarding the notions of "Catholic Hermit", "Temporal vs Mystical Catholic Worlds," etc.

Please note, this article is not meant to answer the simple question about what a Catholic or diocesan hermit is. If you are looking for that kind of post, please see Notes From Stillsong Hermitage, What is a Diocesan Hermit?. The following article is concerned more with the misuse of the term Catholic hermit in contrast to the sense in which the Church uses the term.

Sister, could you please comment on the marked passage? I am confused by some terms, like "temporal Catholic world", but also by the reference to a canonist who seemingly should not be trusted in some of her comments, especially re the definition of "Catholic hermit." Thanks.

[[This was in reaction to being told of some person who may or may not have a canon law degree writing online that hermits who are not canonically approved are not to refer that they are Catholic hermits, for that implies they are canonically approved. Also, such hermits should not have confessors to guide them.... So, we have here an example of someone out in the blogosphere interpreting canon law using personal augmentation and opinion. The reality of a statement of fact can be twisted any which way, but fact is fact. What another wants to think depends upon that others' frame of reference. To be a Catholic hermit means just that: Catholic and hermit. It does not imply or infer the status in the temporal Catholic world known as canonical approval or disapproval. Also, there is nothing in Canon law that states a Catholic hermit ought not be guided or supervised by his or her confessor. Ask a priest canon lawyer.]] (Emphasis added)

Yes, I have actually recently read this very passage even apart from your question, and I also know (as a superficial online acquaintance only) the Canonist who is being maligned and deemed mistaken. She has written that the term "Catholic hermit" necessarily implies canonical status or standing, and I completely agree. I have referenced her comments a number of months back, so you can look for those too if you care to. (The poster who wrote the above passage is correct about frame of reference being important. This person I have cited previously is a canon lawyer who specializes in consecrated life, so she is well-qualified here. She works in and for the Church in this capacity, and her blog is an instance of authoritative information.) But let's look at this now.

On the term Catholic Hermit

If a man says "I am a Catholic priest" does he merely mean, "I am a Catholic and a priest by virtue of baptism into the priesthood of all believers?" No, certainly not, at least not if he means what the Church herself means by this. Does he mean "I function as a priest in the private sector with my minister's web license and am a Catholic, so therefore, I am a Catholic priest? Again, no, of course not. Does he even mean, "I was an Anglican priest, but have since become Roman Catholic; I have not been ordained in the Catholic church, but I am a priest forever, and therefore I am a Catholic priest"? No. Similarly, if a lay woman says she is a Catholic nun, does she mean she is Catholic, dresses simply, is cautious in her spending habits, and prays regularly? Again, not if she means what the church means by these terms.

The church herself has raised the publicly vowed eremitical vocation to the consecrated state and public standing in law, and because she has, a Catholic hermit is not simply a "hermit" (in the common sense of the term) who is Catholic. (To be very blunt, if that were the case, and were he Catholic, Theodore Kasczynski (the "hermit" Unabomber) could have called himself a Catholic hermit; so could any curmudgeonly loner, misanthrope, or agoraphobic living alone, for instance, so long as they were baptized Catholic). A Catholic hermit, on the other hand, is one whose vocation is discerned and mediated by the Catholic Church in whose name and in direct and real responsibility to whom the hermit lives her life. Both terms, "Catholic" and "hermit," are important and qualify one another. Not just any form of solitary living is authentically eremitical despite the common sense of this term (cf Kasczynski or the misanthrope again). Similarly then, not every form of genuinely eremitical life is Catholic in the normative sense of that term; that is, not every genuine eremitical life is undertaken with the authority and in the name of the Catholic Church. In this matter the Church recognizes certain individuals as publicly representing the vocation, and she grants both commensurate rights and obligations along with the title Sister or Brother to these. The RIGHT to call oneself a Catholic hermit is implicitly granted by the Church in a definitive liturgical act (". . .be faithful to the ministry the church entrusts to you to be carried out in her name"); it is not and cannot be assumed by the individual on her own authority.

Similarly, if the term "Catholic hermit" is used by someone to describe herself, others have have every right to infer that the person has the official standing to act and style herself thusly in the name of the Church. The rights and obligations of the Catholic hermit do not stop at the hermitage door, nor do they fail to impact others. The vocation of the Catholic hermit, hidden though it may be, is still a public vocation. Again, rights have correlative responsibilities and the designation "Catholic hermit" comes with both. Misuse of the label opens the way to misrepresentation of all kinds simply because one who is not canonical may not understand, appreciate, or even care about the commensurate obligations that come with profession and consecration as a Catholic hermit, much less feel bound to exercise them. Accountability, formal, legitimate, and real is associated with the term Catholic Hermit.

The Canonist referenced in these comments has merely pointed out the normative Catholic meaning of such terms, and in this I believe she is completely correct. She has twisted nothing and her credentials are not in question. Neither, as far as I can tell, is she merely offering personal opinion here; she speaks as a Catholic canonist!

Note: after I wrote this article I discovered Canon 216. It says the following: [[All the Christian Faithful, since they participate in the mission of the Church, have the right to promote or sustain apostolic activity by their own undertakings in accord with each one's state and condition; however, no undertaking shall assume the name Catholic unless the consent of a competent ecclesiastical authority is given.]] Thus, the prohibition is present in black and white. The argument that one need merely be Catholic and a (lay) hermit to call oneself a "Catholic hermit" is specious. The same is true of a religious community and the term Catholic. One must be using the term in the way the Church herself does, and be doing so with the authority of the Church, otherwise the usage is illegitimate at best. See also Canon 300 which applies to groups: No association shall assume the name "Catholic" without the consent of ecclesiastical authority in accord with the norm of C 312

Can Hermits be Guided by Confessors?

As for the issue of not being guided by a confessor, you didn't ask about this explicitly, but it is included in the passage and is one of the things the canonist was said to be wrong about so I will address it here: I believe the author of the passage you asked about is referring to the same entry on eremitical life by the referenced canonist, but has completely misread or miscontrued what she said. What was affirmed was that a hermit's spiritual director ought not to also be her superior. Here is the accurate passage, at least from the same entry on hermits: [[. . .Normally, it is best if the superior is not his [the hermit's] spiritual director unless exceptional circumstances call for it and if the extent of the obedience owed is clearly spelled out in the hermit’s rule of life. Otherwise, the private hermit should not make a vow of obedience but should content himself with the vows of poverty and chastity. The vow of obedience more properly belongs to the applicable canonical forms of consecrated life, not to private individuals who are not living in community or under hierarchical authority.]] Despite it not sounding like the correct passage (it does not mention confessors), as far as I know, this is the only reference to hermits in which the same author refers in wisely cautionary terms to specific arrangements re spiritual directors as superiors, but in no way does this suggest a spiritual director should not guide a hermit. Quite the opposite, in fact, is presupposed.

Temporal vs Mystical Catholic Worlds

The term Temporal Catholic World (and its implied "opposite," Mystical Catholic World) can indeed be confusing. It is a neologism of sorts, so is somewhat idiosyncratic and eccentric. In some senses I find it theologically objectionable because in the passages I read at least, it is counterposed with the phrase Mystical Catholic World and the two tend to be played off against one another as though they are completely distinct and oppositional. [The marked passage above does not refer explicitly to "mystical Catholic world" but others did.] But for the Christian this cannot be claimed to be true without emptying the Incarnation of meaning. Is there any question that Jesus was a mystic? No. So was Paul, but neither of these played off the temporal world against the so-called mystical world. Neither rejected one in the name of embracing the other. In fact, Jesus' entire role as mediator is a matter of making sure these two dimensions of the one world interpenetrate one another in a more and more definitive way.

A Catholic is called to live in this world of space and time. She is called to live out her faith in Christ in a world which is yet incompletely redeemed, and in this way to be in it even if not "of it". She is called to understand that with Christ the separation between sacred and profane has been broken down, the veil rent in two. S/he may be called to be a mystic, and yet, his/her contemplative life can spill over into ministry other than prayer. It MUST spill over into love of others! Those who are truly contemplatives or authentic hermits know this phenomenon well. Does it require care in making sure the active ministry one undertakes is the fruit of contemplative life? Yes, absolutely. Should active ministry always be undegirded by and lead back to prayer? Again, absolutely. But union with God necessarily leads to love of others in unmistakable and concrete ways, and therefore quite often to more direct or active ministry, how ever that is worked out by the individual.

It is true that there is a rare vocation to actual reclusion, but recluses are also in communion with the church and larger world -- in some ways to a greater extent than most people. Their reclusion is actually a paradoxical way of assuming responsibility for (and in) "the world", both within and without the recluse's own self. Remember that prayer links us in God to all others (we all share the same Ground of Being and Meaning), and that love of God issues in love of others, a concrete love, not love as an abstraction or pious parody of itself. At the same time, our love for others reveals God to us and casts us back into his arms so that we can be remade sufficiently to love all the more truly and profoundly. As a friend recently reminded me, "In solitude we should hear the cries of the world. It takes strength. And if you don't hear that cry, you are not mature enough. . ."

Mystics though any of us may be, we are all still "temporal world Catholics". Or perhaps the paradox is stronger and truer as it often is in Christianity: to the degree we are true mystics and citizens of heaven, we belong even more integrally to the temporal world loving it deeply and profoundly into wholeness. Never do we abandon it! Eremitical vocations (including reclusion), undoubtedly require "stricter separation from the world," in the sense defined below, but they do not allow us to divide reality into a temporal Catholic world and a separate and opposing mystical Catholic one, especially when that division (which could be used in a more typological sense otherwise) is accompanied by the implication that hermits in the "TCW" (read canonical or diocesan hermits!) are not given to contemplation or union with God, or the direct affirmation that a hermit needs to discern whether she is called to one or the other of these "worlds." [[So what hermits ought consider in discerning their vocation, is if he or she is called by God to be a temporal Catholic world hermit or a mystical Catholic world hermit. . . .]] This kind of stuff is simply theological nonsense, not least because any hermit alive today and every living Catholic mystic is alive in the "temporal Catholic world" (how could she NOT be?); further, both requires much from, and owes much to, that very world --- not least the recognition of its sacramental character as well as commitment to its continuing redemption and perfection in Christ! It is precisely the mystic (hermit or not) who appreciates all this most clearly!

The term, "world" in the phrases "hatred for the world" or "stricter separation from the world, " as I have written before, needs to be defined with care to prevent such theological nonsense. In Canon Law the term refers to "that which is yet unredeemed and not open to the salvific action of Christ," not least, I would add, that reality within ourselves! (A Handbook on Canons 573-746, "Norms Common to All Institutes of Consecrated Life," Ellen O'Hara, CSJ, p 33.) I have referred in the past here to "the world" as that which promises fulfillment apart from Christ. Neither of these complementary definitions suggests the wholesale renunciation of temporal for mystical, or supports the invalid and simplistic division of reality in such a way. Instead, both look to a certain ambiguity in temporal existence, and look to its perfection and fullness of redemption in Christ; rightly they expect Christians to open the way here. I hope you will look past relevent posts up --- especially re the notion that the world is something we carry within us, and not something we can simply or naively close the hermitage door on!

Again, I am reminded of several passages from Thomas Merton in regard to this last issue,

"When 'the world' is hypostatized [regarded as a distinct reality] (and it inevitably is), it becomes another of those dangerous and destructive fictions with which we are trying vainly to grapple.

or again,

And for anyone who has seriously entered into the medieval Christian. . . conception of contemptus mundi [hatred for or of the world],. . .it will be evident that this means not the rejection of a reality, but the unmasking of an illusion. The world as pure object is not there. it is not a reality outside us for which we exist. . . It is only in assuming full responsibility for our world, for our lives, and for ourselves that we can be said to live really for God."

as well as,

"The way to find the real 'world' is not merely to measure and observe what is outside us, but to discover our own inner ground. For that is where the world is, first of all: in my deepest self.. . . This 'ground', this 'world' where I am mysteriously present at once to my own self and to the freedoms of all other men, is not a visible, objective and determined structure with fixed laws and demands. It is a living and self-creating mystery of which I am myself a part, to which I am myself my own unique door. When I find the world in my own ground, it is impossible for me to be alienated by it. . ." (The Inner Ground of Love)

or again:

"There remains a profound wisdom in the traditional Christian approach to the world as an object of choice. But we have to admit that the mechanical and habitual compulsions of a certain limited type of Christian thought have falsified the true value-perspective in which the world can be discovered and chosen as it is. To treat the world merely as an agglomeration of material goods and objects outside ourselves, and to reject these goods and objects in order to seek others which are "interior" or "spiritual" is in fact to miss the whole point of the challenging confrontation of the world and Christ. Do we really choose between the world and Christ as between two conflicting realities absolutely opposed? Or do we choose Christ by choosing the world as it really is in him, that is to say, redeemed by him, and encountered in the ground of our own personal freedom and love?" (The Inner Ground of Love, Emphasis added)

And finally (I have quoted this before):

"Do we really renounce ourselves and the world in order to find Christ, or do we renounce our own alienation and false selves in order to choose our own deepest truth in choosing both the world and Christ at the same time? If the deepest ground of my being is love, then in that very love and nowhere else will I find myself, the world, and my brother and my sister in Christ. It is not a question of either/or, but of all-in-one. It is not a matter of exclusivity and "purity" but of wholeness, whole-heartedness, unity, and of Meister Eckhart's gleichkeit (equality) which finds the same ground of love in everything."

I think, unfortunately, it is possible to read a lot of medieval mystical theology which is built on a notion of the world and contemptus mundi or a mundo secessu (as used today in Canon 603) that does indeed falsify the situation and makes difficult to see or make the real choice before us Christians. Yes, we must discern whether we are called to contemplative or active life (or to which of these essentially or primarily), to eremitic or even reclusive life or to apostolic or ministerial life, and of course, if God gifts us with mystical prayer, we need to honor that, but again, all this happens in the temporal world and as a gift to that world. In light of the incarnation, and especially in light of our own relational human constitutions as imago dei trinitates and grounded in God who speaks in and through us, that is precisely where God is to be found. Heaven and earth interpenetrate one another in light of the Christ Event and our task is to allow that to be more and more the case in Him. Setting up false, absolute, simplistic, and destructive dichotomies is no help at all.

I hope this helps. As always, if it is unclear or raises further questions, please email me.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:07 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A Vocation to Love, Canon 216, Catholic Hermits, Contemplation and action, Diocesan Hermit, Ecclesial Vocations, non-canonical vs canonical standing, Stricter separation from the world, Thomas Merton

13 November 2008

On the Importance of Lay Hermits and the Lay Hermit Vocation

I know I have written a lot in this blog about the significance of the call to diocesan eremitism and about the theology of the vocation to the consecrated state, the importance of canonical status, etc. Thus, while I believe strongly in the importance of the lay vocation, it is not always one which I can convincingly argue for as a diocesan hermit myself. However, the truth is that in our church and world, the majority of hermits will always be lay or "non-canonical" hermits, not those called to consecrated life (i.e., the consecrated STATE of life), but called to a dedication of self rooted in their baptismal consecration and every bit as real and demanding.

Because I belong to a listserve of those interested in becoming hermits, or in aspects of the life for other reasons, the whole question of approaching dioceses for admision to canonical profession and consecration comes up often. In the last few days however I received letters from 1) a priest who had decided NOT to seek canonical "recognition" because of something I had written (I put the word recognition in quotes because it needs to be seriously qualified to be used), and 2) a woman living as a hermit who had found some of what I had said on this matter helpful; she may seek canonical approval and standing, but then again, she may not. Both reminded me that the lay hermit has really significant witnesss and encouragement to give to this world, and to our church as well. Because of this, I wanted to post some of what I wrote recently in response about the lay hermit vocation. It is similar to a post I put up recently on the notion of becoming living temples of the Holy Spirit/God. The letter I am responding to is included in italics and emboldened. I have not included the entire text here.

[[May God Bless you for your wonderful replies. I can not tell you how much you have helped me in this understanding of different, yes, but yet not. How often I have read this law, and so often lost some part, an important part of its beauty and grace and open call to us all so inclined to give our lives in holy consecration and celebration of God with us in the ordinary of life now.

In my own part of the country there is little understanding of Canon Law 603. I have been living my life as one of the "non"s for some time, several years - ten years with spiritual direction and a rule of life, waiting on the Lord for the "recognition" from the church ( I have not made "final vows, in the wake of scandals and finance problems and illnesses we have gone through a few Bishops in our post in very recent years and those who have come are not as familiar with this calling as it would be in your country.

Well, don't be too sure there is a huge familiarity in the US either! There is some, certainly, but Bishops remain hesitant and some are suspicious. My own journey to perpetual eremitical profession (I was already finally professed otherwise) took almost 25 years precisely because my (former) Bishop had reasons to back off from professing ANYONE under Canon 603. Thus, Vicars accepted candidates -- only later (several years down the line) to learn there would be no professions. Others on this list have similar stories in terms of length of time (17 years, etc.) to perpetual profession. There remain dioceses that either have never had strong candidates or who continue to have no experience of the Canon for other reasons -- including a refusal to use the canon at all.

It is quite common to hear stories from persons approaching dioceses wishing to be professed as diocesan hermits who are told, "just go off and live in solitude; that is all you need" or who run up against Vicars who neither understand nor see the importance of the life. I think it is a huge responsibility for a Bishop to take on a person in the way Canon 603 envisions (not that it is an onerous one though!), and many seem resistant to this for one reason and another as well. Anyway, what some of us have found is that dioceses across the board need education, resources, and assistance in understanding the vocation and how Canon 603 plays out on the ground. It is more unusual to find a Bishop open to Canon 603 and willing to accept responsibility for diocesan hermits than not.

[[However, I have a very close relative who is "recognized" and this has been a great support to me and my own journey. I know too my own efforts to authentically live this call and service has encouraged her too...she often considers herself an urban hermit - one who lives in an urban area ( there really is no official title as such is there?) where as, I live in a very rural and secluded area. There have been times I have felt real persecution by those who were "really consecrated". I have been told that I was a "pseudo-hermit" and "not real", or not deserving of the same benefits and graces of this special call.]]

One of the things hermits generally know is that whether canonical or non-canonical, consecrated or lay, the eremitical life is a significant one which speaks in different ways to different segments of the church and world. The Church wants so much to truly esteem the lay vocation today and eremitical life lived apart from Canon 603 is one of the really significant ways the Holy Spirit is working in our church today. The notion that someone who is not Canon 603 is not a ""real hermit" or is "pseudo" is plain nonsense and must be combatted. One of the ways that will happen is if people get on with living eremitical lives without worrying about consecration and profession or the legal rights and responsibilities which come from these things. Some will discover they actually require the canonical standing and structure -- and are called to take on the added responsibilities of this state, but others --- MOST others --- will begin to discover the mission and vocation to lay eremitical life which is capable of speaking so poignantly to a world in need of this witness. Whether canonical or non-canonical the call is real and significant. I personally think it is important to know that experientially BEFORE one approaches a diocese for admission to public profession, and that requires time.

I also am an urban hermit. It is a term I first heard used by Thomas Merton when he reflected on the need for hermits in the unnatural solitudes of the cities. However, there were a kind of hermits in the Medieval Church in Italy known as urbani, so the term is not novel with Merton. It is an historical term, not merely a neologism, therefore, a designation which contrasted with hermits living in other situations. Evenso, the idea of urban hermits is one which some hermits reject because the idea of wilderness is being defined so differently than they are used to. However, I cannot tell you the number of ill and elderly who live lives of what could well become eremitical silence and solitude in these places (eremitical, that is, instead of isolated) --- eremitical vocations we have only just begun to recognize and understand.

For these people in particular, people who have no choice about physical solitude or leaving it for weekends, etc, the witness we hermits each give is that such unnatural physical and emotional solitudes can be redeemed and become true oases in the desert. That is, what is physical and emotional isolation can be transformed into genuine eremitical solitude. And, while I am consecrated under Canon 603 and very glad of it, I realize that it is the lay hermit who would witness more powerfully for these people. Yes, I have things to say with my life to such people because of my own circumstances, but in some ways my consecration ALSO distances me from the witness I could give them, for they know they will never seek such standing in Law (they do not FEEL CALLED TO THIS) even while they yearn to know that the lay vocation they are living right now is ultimately meaningful. A cloud of lay hermits in the church could do that and I pray that it happens in the 21st century as it did in the 3rd and 4th (etc), or the 10th and 11th C.!!

We need laity living eremitical solitude faithfully to speak in the ways only they can. It is SO very important, and actually not something I realized I would be definitively distancing myself from in various ways until after it had happened. In any case, hermits are hermits, and whether consecrated (made part of the consecrated state by God through his Church) or lay, both are real, both are significant and inspired, both speak to our world and church in their own ways. Part of the problem is that we really still are suffering from the failure to esteem the lay vocation. We misunderstand the notion of states of perfection and refer to some vocations per se as higher than others --- again misunderstanding and misconstruing what SHOULD REALLY be meant by such feeble and dangerous language. The Church has not completely managed to free herself from this tendency, or from associating the notion of status with higher and lower levels of contribution to the life of the Body of Christ and to the world. If we do manage to free ourselves from these things I predict it will be non-canonical or lay hermits who are pivotal in the achievement. But that means, at the very least, refusing to buy into the notion that Canon 603 eremiticism is better or more genuine than non-canon 603 eremiticism. It is different in its responsibilities and witness, but not better.

[[I thought it was a strange mentality to have towards others, it was wounding and hurtful to me and for a number of years I considered not living this call on my heart for fear of their words being true and I was not worthy to be mimicking others in such a way or worse, that I was offending in some way Our Holy Mother Church by my actions!. Your words are surely Spirit led, especially in these times of changes and concerns, where there sometimes seems to be more church closings than vocations.]]

There seem to be more church closings than new RELIGIOUS vocations, which is what I know you meant, but vocations per se? Not at all. Again, as I posted a few days ago, we are so used to associating the term vocation with religious vocations or vocations to the priesthood that we do not adequately esteem what it means to be called to LAY life. And again, apart from Vatican II, the Church hierarchy has not always been helpful in correcting or rectifying this lack. Instead she has underscored it and we are reaping the harvest of that as we speak. She has also contributed to the mistaken idea that only religious with vows of celibacy, etc., REALLY live lives of prayer, of wholehearted generosity and self-gift. Most of us are called to lay vocations, and that means most hermits as well. It would be wonderful to see the widespread recognition that this is a HUGELY significant vocation and to watch it flourish.

Many thanks for your kind words. They mean a lot to me. Continue to take hold of your eremitical vocation and see where the Holy Spirit leads. The need for hermits in our contemporary world cannot be overstated but only a few of these will be called to the consecrated state of life. After all, that is not really where the need is most outstanding, I think. Wherever the Spirit leads it is to a REAL vocation and REAL eremitism. There is no doubt about that.

Sincerely,

Sister Laurel, Er Dio

Stillsong Hermitage

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:08 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Catholic Hermits, Diocesan Hermit, Lay hermits vs diocesan hermits, non-canonical vs canonical standing, Thomas Merton, unnatural solitudes, urban hermits

05 August 2007

Thomas Merton, a brief public defense

Recently I participated in a discussion about Thomas Merton. It was a discussion in which some were quite critical of him, his later writings, and concluded that he was no real monk (he was said to be "inauthentic" and even supposedly hypocritical), and his later writings were to be eschewed except by "more advanced souls" who would not be led astray. Well, some of this discussion rankled with me, not only the idea that another monk could publicly state that, "He talked the talk, but he really didn't live the life," and especially the idea that Merton's work was B.S, in the sense that Merton had pulled the wool over the eyes of an unsuspecting and gullible world. I believe that to be a misconstrual of Merton's actual meaning, even if the exact words are correct. The simple fact is I owe my vocation to Thomas Merton in some senses, and because of that, I also owe him a public defense. The following is an excerpt from the comments of a critic of Fr Louis's, and my response.

[[A Trappist monk once told me that Fr Merton entered into a room and saw bookshelves full of all his writings and he laughed. A friend who was with him asked him why he was laughing. He nodded towards his writings and replied " half of that is just B.S!!!! ]]

And Aquinas, at the end of his life, characterized all of his writings and thought as just so much straw, dross, waste ready for the fire. There are two ways to read the term bullshit. The first either is or includes a verbal or active sense: it implies the act of fraud or hypocrisy --- as a freshman in college might BS their way through a presentation without really knowing what they are talking about. The second is simply a comment on the quality of the work. It means that in comparison with real brilliance or the incommensurability or ineffability of the thing being described, one has done a terrible (that is, all-too-human) job. In fact, we don't know how Merton was using the term (as an apophatic contemplative he could simply have recognized every statement about God experienced in prayer is also a kind of betrayal of the God of intimacy who is always wholly other too), but I don't think we should conclude facilely that he meant his work was "fraudulent," any more than we should do so with Aquinas' comment about his own work.

You have actually cited only two monks who made comments regarding Merton, and the simple fact is, we may be seeing their flaws (judgmentalism, envy, narrowness of vision for instance) more than we are seeing Merton's. (Anyone living in community for any time at all will recognize the phenomenon that occurs when a fellow Brother or Sister is brilliant or particularly gifted in some way, and those who are more mediocre in many (or at least some of those same) ways, evaluate them. Monasteries do not lack for pettiness just because the members are monks and nuns.) But we must ask ourselves, in light of such accounts, "If Father Louis was not living the life, why was he permitted to move through all the stages of formation, profession, ordination and the like? If his work was hypocritical, then why did the Order allow it to be published? Why was he allowed (indeed at times exhorted and commanded) to continue an activity which was contributing to and would therefore have exacerbated his hypocrisy? If he was not REALLY Cistercian, why, in fact, was he allowed an intimate role in the formation of novices, juniors, etc?" Other Cistercians and monks of other Orders and monasteries recognize Merton as "the real deal," and they know quite well, there is no ideal monk, no one who REALLY lives the life without ALSO struggling with the life.