[[Dear

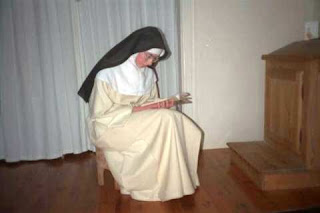

Sister, Thank you so very much for your thoughtful and detailed response

to my question.(cf., Questions on Formation) I suppose the one thing I fret about the most is my

prayer life. I believe I have found a rich but simple way to pray that

incorporates lectio and the psalter. It's modelled on the Liturgy of the Hours

but is very simple. I find it very life giving. Part of what I like about it is

its simplicity, ease of use and flexibility: For example here is what

Morning Prayer looks like.... O God, come to my assistance etc. , Psalm 95 (Invitatory) Hymn (Usually the Eastern Orthodox "O Heavenly King"

prayer to the Holy Spirit). Three Psalms (I pray 3 psalms, in order, at

each office). 1 chapter from the OT and one from the NT. Contemplative/Intercessory Prayer, Our Father, Hail Mary, Benedictus, Closing collect (usually collect of the day from the

Missal). Evening prayer is similar

except it has the Examination of conscience, Magnificat etc. I do keep track of feast days

and the liturgical seasons as well. [A reference to Compline was excerpted here]

[[Dear

Sister, Thank you so very much for your thoughtful and detailed response

to my question.(cf., Questions on Formation) I suppose the one thing I fret about the most is my

prayer life. I believe I have found a rich but simple way to pray that

incorporates lectio and the psalter. It's modelled on the Liturgy of the Hours

but is very simple. I find it very life giving. Part of what I like about it is

its simplicity, ease of use and flexibility: For example here is what

Morning Prayer looks like.... O God, come to my assistance etc. , Psalm 95 (Invitatory) Hymn (Usually the Eastern Orthodox "O Heavenly King"

prayer to the Holy Spirit). Three Psalms (I pray 3 psalms, in order, at

each office). 1 chapter from the OT and one from the NT. Contemplative/Intercessory Prayer, Our Father, Hail Mary, Benedictus, Closing collect (usually collect of the day from the

Missal). Evening prayer is similar

except it has the Examination of conscience, Magnificat etc. I do keep track of feast days

and the liturgical seasons as well. [A reference to Compline was excerpted here]

On "hermit days" (days I can live

in total solitude, like Saturdays and Sundays, because I still work in the

world) I also pray the Angelus, Rosary and do other spiritual reading and

journaling (in addition to exercise and some physical labour). Morning, Evening

and night prayer are my foundations no matter what. I also spend long periods of

the holidays and summers in solitude (I'm a teacher). As you can see,

slowly but surely a rhythm of life is emerging as I experiment with this life

and grow in it. I'm sorry if this email is long winded but I was hoping

you could answer a few questions for me...

1) Do you think what I've

described is an effective way to pray as a hermit (at least formally as your

really praying all day)? This has become a very small point of disagreement

between me and my director. He keeps saying I should pray the official LOTH. I

tell him that I respect it but the mechanics of it drives me nuts. I like

praying the full Psalms uninterrupted, I like that my prayer isn't constantly

interrupted by flipping and rubrics etc. I like that when I pray I come before

The Lord with just my Bible and before an icon of Him and Our Lady I pray in

simplicity. I wonder that if God calls me to this life that I'll

have to abandon this form of prayer for the LOTH. I know obedience is essential,

but do you think that hermits are allowed to pray more freely than diocesan

priests and religious? I know many monastic communities have crafted their own

version of the office. Thoughts, advice and insights on this are greatly

appreciated. ]]

First, I am glad my last post (cf., Questions on Formation) was of assistance to you. Many thanks as well for permission to post your response with its set of questions and especially some of the description of how you are proceeding in embracing the eremitical life more and more. I think they can be helpful to others who are looking for ways to do something similar.

On the Phrase "Still work in the world":

Before I move on to your questions though, allow me one quibble with your use of the term "the world" as in "I still work in the world." There are some "hermitages" (or putative hermitages!) that are every bit as much or more "the world" than the region you are describing. Remember that "the world" in the pejorative sense, the sense that canon law primarily refers to with c 603's,"stricter separation from the world" or the sense monastic mainly mean when they refer to fuga mundi (flight from the world), as well as the meaning of the term in the early Greek and/or Desert Fathers, was not the world as a whole (which they saw as God's good creation), nor even the populated world (which was ambiguous though essentially good), but rather, "that which is resistant to Christ."

Before I move on to your questions though, allow me one quibble with your use of the term "the world" as in "I still work in the world." There are some "hermitages" (or putative hermitages!) that are every bit as much or more "the world" than the region you are describing. Remember that "the world" in the pejorative sense, the sense that canon law primarily refers to with c 603's,"stricter separation from the world" or the sense monastic mainly mean when they refer to fuga mundi (flight from the world), as well as the meaning of the term in the early Greek and/or Desert Fathers, was not the world as a whole (which they saw as God's good creation), nor even the populated world (which was ambiguous though essentially good), but rather, "that which is resistant to Christ."

I have written about this before, but let me quote from a commentary on John Climacus' Ladder. Climacus is quite strict in his approach to solitude but he can also be misunderstood when read literally and unhistorically. Thus, Vassilios Papavassiliou writes: "In this sense, 'the world' means all those things that are opposed to Christ and to our salvation. The world in the sense of God's creation is good, and we are all (even those living monastic life) a part of it. However remote monasteries or hermitages may be, all monastics lie beneath the same sun and moon, breathe the same air, and share the soil and the fruits of the earth with all humanity . . . There can be no ascetic life, no true spirituality of we are not willing to break with the world in terms of what we hold dear and what constitutes the focus of our lives. . ." (Thirty Steps to Heaven, The Ladder of Divine Ascent for all Walks of Life, Ancient Faith Publishing, 2013) Canonists reflecting on the canons on religious life say something very similar in the Handbook on Canons 573-746: "'The world' is that which is unredeemed and resistant to Christ."

If you get in the habit of referring to everything outside your own home as "the world" you will be buying into a false dichotomy which idealizes your own physical space and demonizes that which is other while you also neglect the fact that "the world" in the pejorative sense is more primarily a matter of the heart and who has a claim on that than it is a reference to a geographical region. Moreover you will be setting yourself up for a spiritual elitism which is incapable of perceiving the inbreaking of the Kingdom in the unexpected or unacceptable place --- the very thing that happened to the Pharisees and led to Jesus' crucifixion --- or of standing in solidarity with others outside your home.

If you get in the habit of referring to everything outside your own home as "the world" you will be buying into a false dichotomy which idealizes your own physical space and demonizes that which is other while you also neglect the fact that "the world" in the pejorative sense is more primarily a matter of the heart and who has a claim on that than it is a reference to a geographical region. Moreover you will be setting yourself up for a spiritual elitism which is incapable of perceiving the inbreaking of the Kingdom in the unexpected or unacceptable place --- the very thing that happened to the Pharisees and led to Jesus' crucifixion --- or of standing in solidarity with others outside your home.

Similarly you will be viewing a world which is essentially and always potentially sacramental through a lens which prevents us from seeing that clearly. Finally, you will be at least subtly encouraging yourself to refrain from or avoid the conversion necessary to allow God's love to overcome the resistances within your own heart --- the most persistent and dangerous instances of "the world" any of us ever know. While I don't think you are guilty of this (I really can't know this) to shut the door of one's cell and to believe that one has thus effectively shut out "the world" is often merely a pernicious and arrogant deceit --- something that is one of the surest signs of a dangerously destructive worldliness. What is ordinarily much truer is that at best, we shut the door on the world out there so that, through the grace of God, we can do battle with the demons and world within us! Moreover, we do so in order to love our world and all that is precious to God into the wholeness for which it is made.

On the Way you are Praying, Strengths and Weaknesses:

Now, regarding the way you are praying, I think it has significant strengths and some weaknesses as well. At this point I think the strengths far outweigh the weaknesses, but you should be aware that could change in time, especially as your life in solitude matures, and you will need to be open to that. One primary rule in prayer is always to pray as you can, not as you can't and you are doing that. You are creating and living a rhythm which will structure your entire life in time, and you are integrating lectio (or at least you have allowed for the opportunity to integrate lectio) into your prayer. Within your praxis of LOH you are combining psalmody, intercession and contemplative prayer in what will become an effective invitation to transition from one to another in the whole of your life. Finally, you are finding practical ways to center your prayer life on Scripture. My evaluation of all of this is very favorable. You show you have spent time thinking about this and the fact that you are attending to your feelings as well is significant and positive.

The weaknesses I mentioned are the result of the lack of variation in your office. You see, the official LOH re-enacts the rhythm from creation to death to resurrection and recreation. It does this again and again every day, every week, and over the space of the liturgical year. The hymns change, the antiphons do the same so that they can serve to highlight the main themes of the hours and tie them together with the readings and the season as well. The psalms are chosen for their themes and their relation to the time of day, season, etc. Ordinarily the entire psalm is not used at a given hour because the entire psalm tends to reflect different moods, tones, and themes. (There is similar point to the way readings are chosen, not only to highlight a particular theme but to choose a pericope which is conducive to lectio --- something whole chapters may not do or be.)

The purpose of the LOH is not simply to get us through all 150 psalms each day or week as early approaches to the Work of God did in their effort to pray without ceasing and sanctify the day, but to sanctify and celebrate (make prayer of) all of the moments and moods of human life in light of the rhythm of God's history among us

as we mark that each day and over longer periods via the liturgical calendar. The emphasis differs. If you continue to pray the stripped down Office you have described

without eventually participating more and more in the official LOH (or in a version of that adopted by the Camaldolese, Franciscans, Dominicans, etc which also use several week cycles, varying hymns and antiphons, and include Night prayer which can be sung and memorized easily) you miss many opportunities for making the whole of your life a prayer which resonates with the Church's official prayer. While this is not apt to be a matter of obedience in the narrow sense of someone in authority telling you to do this or refusing to profess you, it is likely to be a matter of obedience in the broader and more profound sense of hearkening to God's voice as it comes to us in the Church's liturgical life.

It is true the LOH is not easy to learn, especially on one's own. A large part of learning to pray it has to do with aural memory and an inculcation of its various rhythms (sound, gesture, etc) all of which are best experienced in choir and in community. Though I regularly sing Office I miss praying it in community and am still reminded of that every time I pray it. Even so its complexities are indicative of its richness and its ability to speak to, console, challenge, and convert us in every moment and mood of our life. I suspect your director knows this and may be coming from this POV rather than another more superficial one.

At this point in time you do not necessarily need to change the way you are praying, but I would seriously suggest you find a 1 volume copy of the Office (a book called Christian Prayer which has very little flipping back and forth) to supplement your current praxis. (If and when you decide to do this your director can assist you in doing so in a way which respects both your preferences and the important diversity and richness of the LOH. In learning the use of the LOH you may find it challenges temperamental tendencies or strengths within you so be aware that your preferences may be rooted both in your response to God as well as in your personal insecurities and resistance to the movement of the Holy Spirit.) Remember that the diocesan hermit's prayer is not only personal but ecclesial and a participation in the Church's own prayer. The LOH is a formative reality, that is, it is one of the major ways the Church forms herself as a People at prayer by forming individuals in the rhythms and themes of her liturgical and Christocentric life.

That said though, let me point out that

only priests are canonically required to pray the LOH. Religious (who are not clerics) are canonically obliged to pray the LOH

according to proper law, that is according to the constitutions of their congregation (or in the hermit's case, the Rule approved by her Bishop). Some hermits I know (I know one presently) do not pray the Office at all (though I admit I do not personally understand how this can be the case). Others, myself included, use the Office book of a specific congregation. I use the Camaldolese office book (consisting mainly of Lauds and Vespers, though it also has Compline); I do so because it is entirely geared to singing the hours and the psalm tones used are both simple and musically interesting (unlike something like the Mundelein office book which I tried a few years ago and found musically tedious). For Vigils, however, I use the four volume LOH, as I do for Scripture readings. Others use Franciscan office books or those of some other tradition. They may supplement their Office book with collections of readings for Vigils like those books (Augustinian Press I think) used by the Camaldolese, etc.

Becoming a Hermit, some Nuts and Bolts:

[[

(2) Is this how a rule is crafted and the embrace of this

life takes place? I think that it would be very hard to go cold turkey and

become a hermit overnight. I'm finding that my immersion into this life and the

crafting of a rule is gradual process. Slowly I'm spending more days alone in

prayer. I'm not being weird about it. I still have life giving friendships and

I'm involved with my family and my parish but the putting on of this life is

happening slowly. I'm 38 years old and I imagine as I discern more and more and

live this life that there will come a time where I naturally embrace this life

full time. I already see it happening by ensuring my weekends and holidays are

"hermit days".

From this I see a rhythm emerging. I like to keep my

prayer life/devotional life very simple (hence my simple prayer office). I think

it was St. Benedict who lauded short and simple prayer. Is this how a

rule is developed? And is this how the call to eremitic life discerned? More insights, thoughts and advice are greatly appreciated. Thank you so very much for your help. Your insights are gold as I try to

figure out this thing the Lord may be calling me to. ]]

Yes, I think generally this is how a Rule comes to be crafted. Over time we pay attention to the things which are lifegiving for us, the ways in which God comes to us, the ways in which we truly give ourselves and allow our hearts to be opened and formed in the love of Christ, etc as well as to those things which are traditionally part of the eremitical life; we build those into our life or otherwise make provision for them in ways which are most advantageous for our growth and an integral obedience to God. As you probably already know, a Rule is not merely a list of do's and don'ts, nor a system of abstract principles or values. It is, in the language of canon 603, a Plan of Life, a plan for the way we can best live our God-given, God-willed lives in the fullest and most integral way possible. You seem to me to be approaching this in just the right way no matter what form of life it leads you to or eventually best expresses (the more definitive Rule or plan of life you eventually write --- for you will probably write several in the next years --- may or may not be an eremitical one).

At this point I would not say you are discerning an eremitical vocation so much as you are discerning the place of prayer and some (perhaps a significant amount of) solitude and silence in your life. Your "hermit" days are what are usually called "desert days" or "days of recollection" and active religious will also take such days. However, at some point you may well make a relatively complete break with the life you live now and embrace one of the silence of solitude. But whether this is as a hermit or a contemplative religious or monastic, a dedicated lay person who enjoys the kind of non-eremitical solitude so many older and retired adults live today, etc, is still unclear, undecided, and untried. While it may be hard to go "cold turkey" and while one can and will certainly grow into this vocation, until one is living fulltime silence and solitude and has undertaken the renunciations and, to some extent, the obligations associated with an eremitical life, until, that is, one has spent time testing the true extent to which solitude has opened the door to one as a way to be one's truest and best self, I don't think one can speak of discerning an eremitical vocation per se.

You may have noticed the post on the new Lifetime series, "The Sisterhood". It has been billed as being about women discerning religious life. In actual fact they are discerning WHETHER to enter a congregation

and mutually discern such a vocation with them. While one can see to what extent one feels immediately drawn to or repulsed by such a life by such experiences, until one actually enters the life, one is discerning something other than the life itself.

Until one risks losing oneself in a radical way on this solitary (or any other vocational) path neither will one be able to discover if it is what God is calling one to and thus, to 'find oneself' there. As you well know yourself, one can take education courses, work as a classroom aide and even substitute teach from time to time but unless and until one takes a fulltime job teaching for both discernment and critical formation, one does not know if one is truly called to it. Eventually one has to put it all on the line and take that job to see. Still, I do think you are preparing and preparing well for eventually embracing the more radical break and risk required to enter into that particular discernment process at some point in time.

Overall then, I believe you are proceeding in just the right way

and in the way you need to do for now. I am impressed with the way you are working on your prayer and penitential life and coming to know yourself (prayer, journaling, creation of a simple version of the LOH, commitment to spiritual direction, etc). More, I am very grateful that you would share this part of your journey here and allow me to comment on it. Thank you again.

[[Dear Sister Laurel, When you write about the inner work you have been doing and the healing it has caused it makes me wonder if you are thinking of leaving your vows as a hermit. I am not quite sure how to ask this but you have written that hermits need to be well to make vows. Do you still hold this? Were you well when you made your vows or did you become a hermit because you were not well? (Please don't get me wrong. I love your blog and I wouldn't have thought of asking about this except for your raising the issue yourself!!!) You have also said that with this inner work you have come to stand in a place where you have never been before (I think I got that right) so could this mean you might be happier doing active ministry and not living as a hermit?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, When you write about the inner work you have been doing and the healing it has caused it makes me wonder if you are thinking of leaving your vows as a hermit. I am not quite sure how to ask this but you have written that hermits need to be well to make vows. Do you still hold this? Were you well when you made your vows or did you become a hermit because you were not well? (Please don't get me wrong. I love your blog and I wouldn't have thought of asking about this except for your raising the issue yourself!!!) You have also said that with this inner work you have come to stand in a place where you have never been before (I think I got that right) so could this mean you might be happier doing active ministry and not living as a hermit?]] One of the reasons eremitical vocations must be carefully discerned over a period of time and require recommendations by longtime spiritual directors, Vicars for Religious, pastors and others, sometimes including psychologists and physicians, has to do not only with the eccentricity of the vocation and the rarity of someone being meant to live a fully human life in the silence of solitude, but with the need to be sure the person's capacity for living this vocation in a healthy and fruitful way is certain. This was one of the first questions my own diocese and Vicar had to ask when they began considering professing me or anyone else under canon 603. Sister Susan Blomstad, OSF (Vicar for Religious and Director of Vocations at the time) travelled to New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur with another Sister to question the prior about this particular question: What did the Camaldolese look for in discerning candidates who could live healthy eremitical lives? Every diocese that has proposed to profess anyone under c 603 has had to deal directly with the same question, not because eremitical life is unhealthy but because it is extremely rare and eccentric.

One of the reasons eremitical vocations must be carefully discerned over a period of time and require recommendations by longtime spiritual directors, Vicars for Religious, pastors and others, sometimes including psychologists and physicians, has to do not only with the eccentricity of the vocation and the rarity of someone being meant to live a fully human life in the silence of solitude, but with the need to be sure the person's capacity for living this vocation in a healthy and fruitful way is certain. This was one of the first questions my own diocese and Vicar had to ask when they began considering professing me or anyone else under canon 603. Sister Susan Blomstad, OSF (Vicar for Religious and Director of Vocations at the time) travelled to New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur with another Sister to question the prior about this particular question: What did the Camaldolese look for in discerning candidates who could live healthy eremitical lives? Every diocese that has proposed to profess anyone under c 603 has had to deal directly with the same question, not because eremitical life is unhealthy but because it is extremely rare and eccentric. I think I have answered all of your questions. If I missed something, or if my responses raise more questions for you please get back to me. Your questions were really excellent and drew from several of my posts or positions written over a period of time; I enjoy responding to those kinds of queries and usually see no reason at all to take offense. For the most part they help me come to greater clarity on things I might never consider directly on my own, so again, thank you. I really want you to feel free to follow up if that is necessary.

I think I have answered all of your questions. If I missed something, or if my responses raise more questions for you please get back to me. Your questions were really excellent and drew from several of my posts or positions written over a period of time; I enjoy responding to those kinds of queries and usually see no reason at all to take offense. For the most part they help me come to greater clarity on things I might never consider directly on my own, so again, thank you. I really want you to feel free to follow up if that is necessary.