Several really great questions! Let me give them a shot and then perhaps you can help me follow up on them or clarify what I say with further questions, comments, and so forth. Because shame is such a central experience it truly stands at the center of sinful existence (the life of the false self) and is critical to understanding redeemed existence (the life of the true self). It colors the way we see all of reality and that means our spirituality as well. In fact, this way of seeing and relating to God lies at the heart of all religious thinking and behavior.

But the texts from Genesis tell us that this is not the way we are meant to see ourselves or reality. It is not the way we are meant to relate to God or to others. Instead, we are reminded that "originally" there was a kind of innocence where we knew ourselves ONLY as God himself sees us. We acted naturally in gratitude to and friendship with God. After the Fall human beings came to see themselves differently. It is the vision of estrangement and shame. This new way of seeing is the real blindness we hear of in the New Testament --- the blindness that causes us to lead one another into the pit without ever being aware we are doing so. Especially then, it is the blindness that allows religious leaders whose lives are often dominated by and lived in terms of categories like worthiness and unworthiness to do this.

Religious Language as Shame Based and Problematical

The language of worthiness and unworthiness has been enshrined in our religious language and praxis. This only makes sense, especially in cultures that find it difficult to deal with paradox. We are each of us sinners who have rejected God's gratuitous love. Doesn't this make us unworthy of it? In human terms which sees everything as either/or, yes, it does. This is also one of the significant ways we stress the fact that God's love is given as unmerited gift. But at the same time this language is theologically incoherent. It falls short when used to speak of our relationship with God precisely because it is the language associated with the state of sin. It causes us to ask the wrong questions (self-centered questions!) and, even worse, to answer them in terms of our own shame. We think, "surely a just God cannot simply disregard our sinfulness" and the conclusion we come to ordinarily plays Divine justice off against Divine mercy. We just can't easily think or speak of a justice which is done in mercy, a mercy which does justice. The same thing happens with God's love. Aware that we are sinners we think we must be unworthy of God's love --- forgetting that it is by loving that God does justice and sets all things right. At the same time we know God's love (or any authentic love!) is not something we are worthy of. Love is not earned or merited. It is a free gift, the very essence of grace.

Our usual ways of thinking and speaking are singularly inadequate here and cause us to believe, "If not worthy then unworthy; if not unworthy then worthy". These ways of thinking and speaking work for many things but not for God or our relationship with God. God is incommensurate with our non-paradoxical categories of thought and speech. He is especially incommensurate with the categories of a fallen humanity pervaded by guilt and shame and yet, these are the categories with and within which we mainly perceive, reflect on, and speak about reality. In some ways, then, it is our religious language which is most especially problematical. And this is truest when we try to accept the complete gratuitousness and justice-creating nature of God's love.

The Cross and the Revelation of the Paradox that Redeems

It is this entire way of seeing and speaking of reality, this life of the false self, that the cross of Christ first confuses with its paradoxes, then disallows with its judgment, and finally frees us from by the remaking of our minds and hearts. The cross opens the way of faith to us and frees us from our tendencies to religiosity; it proclaims we can trust God's unconditional love and know ourselves once again ONLY in light of his love and delight in us. It is entirely antithetical to the language of worthiness and unworthiness. In fact, it reveals these to be absurd when dealing with the love of God. Instead we must come to rest in paradox, the paradox which left Paul speechless with its apparent consequences: "Am I saying we should sin all the more so that grace may abound all the more? Heaven forbid!" But Paul could not and never did answer the question in the either/or terms given. That only led to absurdity. The only alternative for Paul or for us is the paradoxical reality revealed on the cross.

It is this entire way of seeing and speaking of reality, this life of the false self, that the cross of Christ first confuses with its paradoxes, then disallows with its judgment, and finally frees us from by the remaking of our minds and hearts. The cross opens the way of faith to us and frees us from our tendencies to religiosity; it proclaims we can trust God's unconditional love and know ourselves once again ONLY in light of his love and delight in us. It is entirely antithetical to the language of worthiness and unworthiness. In fact, it reveals these to be absurd when dealing with the love of God. Instead we must come to rest in paradox, the paradox which left Paul speechless with its apparent consequences: "Am I saying we should sin all the more so that grace may abound all the more? Heaven forbid!" But Paul could not and never did answer the question in the either/or terms given. That only led to absurdity. The only alternative for Paul or for us is the paradoxical reality revealed on the cross.On the cross the worst shame imaginable is revealed to be the greatest dignity, the most apparent godlessness is revealed to be the human face and glory of Divinity. These are made to be the place God's love is most fully revealed. In light of all this the categories of worthiness or unworthiness must be relinquished for the categories of paradox and especially for the language of gratitude or ingratitude --- ways of thinking and speaking which not only reflect the inadequacy of the language they replace, but which can assess guilt without so easily leading to shame. Gratitude, what Bro David Steindl-Rast identifies as the heart of prayer, can be cultivated as we learn to respond to God's grace, as, that is, we learn to trust an entirely new way of seeing ourselves and all others and else in light of a Divine gaze that does nothing but delight in us.

This means that, while the tendency to speak in terms of us as nothing and God as ALL is motivated by an admirable need to do justice to God's majesty and love, it is, tragically, also tainted by the sin, guilt, and shame we also know so intimately. It is ironic but true that in spite of our sin we do not do justice to God's greatness by diminishing ourselves even or especially in self-judgment. That is the way of the false self and we do not magnify God by speaking in this way. Saying we are nothing merely reaffirms an untruth --- the untruth which is a reflection of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. It is the same "truth" that leads to shame and all the consequences of a shame-based life and is less about humility than it is about humiliation. God is ineffably great and he has created us with an equally inconceivable dignity. We may and do act against that dignity and betray the love of our Creator, but the truth remains that we are the image of God, the ones he loves with an everlasting love, the ones he delights in nonetheless. God's love includes us; God takes us up in his own life and invites us to stand in (his) love in a way which transcends either worthiness or unworthiness. Humility means knowing ourselves in this way, not as "nothing" or in comparison with God or with anyone else.

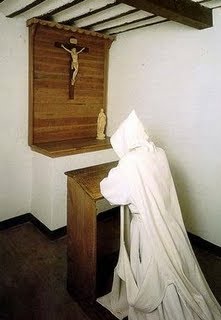

Contemplative prayer and the Gaze of God:

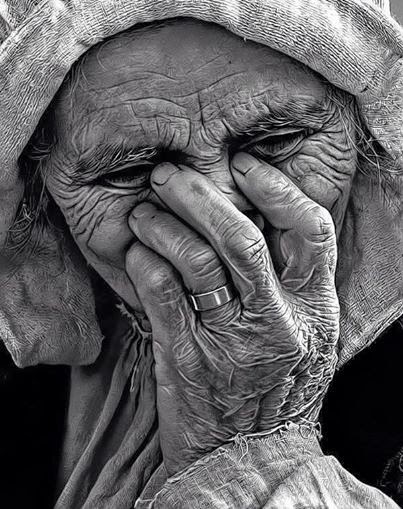

My own sense of all this comes from several places. The first is the texts from Genesis, especially the importance given in those to the gaze of God or to being looked on by God vs being ashamed and hiding from God's gaze. That helps me understand the difference between the true and false selves. The focus on shame and the symptoms of shame (or the defensive attempts to avoid or mitigate these) helps me understand the development of the false self --- the self we are asked to die to in last Friday's Gospel lection. The second and more theologically fundamental source is the theology of the cross. The cross is clear that what we see and judge as shameful is not, that what we call humility means being lifted up by God even in the midst of degradation, and moreover, that even in the midst of the worst we do to one another God loves and forgives us. I'll need to fill this out in future posts. The third and most personal source is my own experience of contemplative prayer where, in spite of my sinfulness (my alienation from self and God), I rest in the gaze of God and know myself to be loved and entirely delighted in. While not every prayer period involves an explicit experience of God gazing at and delighting in me (most do not), the most seminal of these do or have involved such an experience. I have written about one of these here in the past and continue to find it an amazing source of revelation.

My own sense of all this comes from several places. The first is the texts from Genesis, especially the importance given in those to the gaze of God or to being looked on by God vs being ashamed and hiding from God's gaze. That helps me understand the difference between the true and false selves. The focus on shame and the symptoms of shame (or the defensive attempts to avoid or mitigate these) helps me understand the development of the false self --- the self we are asked to die to in last Friday's Gospel lection. The second and more theologically fundamental source is the theology of the cross. The cross is clear that what we see and judge as shameful is not, that what we call humility means being lifted up by God even in the midst of degradation, and moreover, that even in the midst of the worst we do to one another God loves and forgives us. I'll need to fill this out in future posts. The third and most personal source is my own experience of contemplative prayer where, in spite of my sinfulness (my alienation from self and God), I rest in the gaze of God and know myself to be loved and entirely delighted in. While not every prayer period involves an explicit experience of God gazing at and delighting in me (most do not), the most seminal of these do or have involved such an experience. I have written about one of these here in the past and continue to find it an amazing source of revelation.In that prayer I experienced God looking at me in great delight as I "heard" how glad he was that I was "finally" here. I had absolutely no sense of worthiness or unworthiness, simply that of being a delight to God and loved in an exhaustive way. The entire focus of that prayer was on God and the kind of experience prayer (time with me in this case) was for him. At another point, I experienced Christ gazing at me with delight and love as we danced. I was aware at the same time that every person was loved in the same way; I have noted this here before but without reflecting specifically on the place of the Divine gaze in raising me to humility. In more usual prayer periods I simply rest in God's presence and sight. I allow him, as best I am able, access to my heart, including those places of darkness and distortion caused by my own sin, guilt, woundedness, and shame. Ordinarily I think in terms of letting God touch and heal those places, but because of that seminal prayer experience I also use the image of being gazed at by God and being seen for who I truly am. That "seeing", like God's speech is an effective, real-making, creative act. As I entrust myself to God I become more and more the one God knows me truly to be.

What continues to be most important about that prayer experience is the focus on God and what God "experiences", sees, communicates. In all of that there was simply no room for my own feelings of worthiness or unworthiness. These were simply irrelevant to the relationship and intimacy we shared. Similarly important was the sense that God loved every person in the very same way. There was no room for elitism or arrogance nor for the shame in which these and so many other things are rooted. I could not think of my own sinfulness or brokenness; I did not come with armfuls of academic achievements, published articles, or professional successes nor was this a concern. I came with myself alone and my entire awareness was filled with a sense of God's love for me and every other person existing; there was simply no room for anything else.

Over time a commitment to contemplative prayer allows God's gaze to conform me to the truth I am most deeply, most really. Especially it is God's loving gaze which heals me of any shame or sense of inadequacy that might hold me in bondage and allows my true self to emerge. Over time I relinquish the vision of reality of the false self and embrace that of the true self. I let go of my tendency to judge "good and evil". Over time God heals my blindness and, in contrast to what happened after the eating of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, my eyes are truly opened! This means not only being raised from humiliation to humility but being converted from self-consciousness to genuine self-awareness. In the remaking of my mind and heart these changes are a portrait of what it means to move from guilt and shame to grace.

So, again, the sources of my conviction about the calculus of worthiness and unworthiness and the transformative and healing power of God's' gaze comes from several places including: 1) Scripture (OT and NT), Theology (especially Jesus' own teaching and the theologies of the cross of Paul and Mark as well as the paradoxical theology of glorification in shame of John's gospel), 2) the work of sociologists and psychologists on shame as the "master emotion", and 3) contemplative prayer. I suspect that another source is my Franciscanism (especially St Clare's reflections on the mirror of the self God's gaze represents) but this is something I will have to look at further.

.jpg)