[[Hi Sister Laurel! Happy Easter!!! I wondered if you go home for Easter or what you do? If you are with your family or friends I wondered how that works. Do you just talk God-talk or do you talk about other things? Do you have to pretend not to be a hermit or need to "live a double life"? I'm asking because I heard someone saying they had to do that with her family --- I guess she is not Catholic. Is your family Catholic? Does being a hermit mean you only talk about "spiritual things"? You can tell I don't have any idea about this kind of thing so could you tell me a little bit about how you spend holidays and visits with friends and family?]]

[[Hi Sister Laurel! Happy Easter!!! I wondered if you go home for Easter or what you do? If you are with your family or friends I wondered how that works. Do you just talk God-talk or do you talk about other things? Do you have to pretend not to be a hermit or need to "live a double life"? I'm asking because I heard someone saying they had to do that with her family --- I guess she is not Catholic. Is your family Catholic? Does being a hermit mean you only talk about "spiritual things"? You can tell I don't have any idea about this kind of thing so could you tell me a little bit about how you spend holidays and visits with friends and family?]]

Hi there and Happy Easter to you as well! Good to hear from you again. Christ is risen, Alleluia!!

I know I have answered similar questions before so while I will write a new answer for you I hope you will look at On Family Visits and Visits With Friends and perhaps Visiting Family and friends: Followup Question. There are a couple of other posts under the label "Family Visits" which might be edifying, especially as they distinguish being an authentic hermit (that is, being oneself) versus being a stereotype or some sort of imagined "hermit" type. But to answer your questions directly, I don't ordinarily go home for Easter. My liturgical life is centered on my parish and I need to be able to participate there for the sake of my prayer life more generally. Moreover the parish is my faith family so sharing with them to the extent I feel called to do that during any given year is important for the quality of my eremitical life. I might choose to go on retreat during Holy Week and the Triduum, but a home visit is not usually something I would do during this specific time.

But during home visits the one thing I do not do is pretend not to be a hermit. While my family is not Catholic, I do not live a double life at such times --- or at any other time for that matter. I am myself and while I don't expect my family (or my friends) to accommodate me in terms of prayer, liturgy, silence, solitude, meals, etc., I am myself and do not pretend otherwise. To do so is contrary to my vocation and to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. It is contrary to God's reconciling love and will to being and doing the truth within and through me. But consider that neither does this mean I play at some sort of role or adopt the pretense of this or that eremitical character. I am a hermit; I do not play at being one. This means I bring the silence of solitude and eremitical prayer to whatever situation I find myself in. Sometimes (rarely with family) that may mean explicit God-talk (good term, by the way; one I also use) --- as when I am with certain high school friends or Sister friends. But most times it will mean talking about the profoundly human in thoroughly human and everyday terms. After all, that is the way the Spirit works to sanctify any reality, no?

But during home visits the one thing I do not do is pretend not to be a hermit. While my family is not Catholic, I do not live a double life at such times --- or at any other time for that matter. I am myself and while I don't expect my family (or my friends) to accommodate me in terms of prayer, liturgy, silence, solitude, meals, etc., I am myself and do not pretend otherwise. To do so is contrary to my vocation and to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. It is contrary to God's reconciling love and will to being and doing the truth within and through me. But consider that neither does this mean I play at some sort of role or adopt the pretense of this or that eremitical character. I am a hermit; I do not play at being one. This means I bring the silence of solitude and eremitical prayer to whatever situation I find myself in. Sometimes (rarely with family) that may mean explicit God-talk (good term, by the way; one I also use) --- as when I am with certain high school friends or Sister friends. But most times it will mean talking about the profoundly human in thoroughly human and everyday terms. After all, that is the way the Spirit works to sanctify any reality, no?

So, during infrequent home visits or time away with friends, conversations revolve around our lives, our dreams, those we love, and those we struggle to love, the work and relationships which gives our lives meaning, failures, successes, memories, and (sometimes explicitly) the grace of God in all of this. There are walks and shared meals (including grace), remembered past times together, sightseeing, window shopping, and exclamations over shared experiences of beauty and the talent of artisans, lots of laughter, and often serious conversations as well. Is any of this "profane" (outside the precincts of the sacred)? Does any of it fall outside the realm or movement of the Holy Spirit? I don't think so. The compartmentalization of reality (and conversations about reality) into spiritual things and non-spiritual or profane things, especially in light of the Incarnate Christ who tore asunder any veil distinguishing the sacred from the profane, shows a profound misunderstanding of what an authentic spirituality looks like.

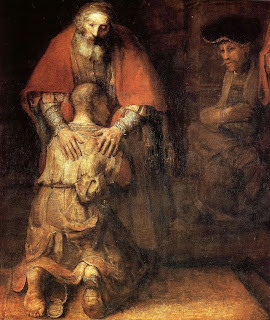

If someone you read claims to be a hermit and said they would only talk about spiritual things with relatives or friends I would suggest the following are true: 1) they are not truly a hermit -- though they may well be an isolated individual playing at being a hermit, 2) they are not possessed of a genuine or at least a mature spirituality, and 3) they are not particularly loving or open in the way they relate to others! Imagine demanding relatives and friends only talk about football, or politics because those dominate your life, or, more specifically, that they never mention the things which really move or excite or concern them because it does not fall within your own narrowly defined "spiritual" bailiwick? This demand limiting what folks can talk about with one is a false attempt to control reality while pointing to one's own supposed "spiritual status" or expertise; it is an implicit and illicit judgment on those whose spirituality may actually be more wholesome and integral than one's own. It certainly seems less pharisaical than a supposed "hermit" who can tolerate nothing but specifically "spiritual" conversation. Hermits live in and towards the silence of solitude but they are not hot house plants that cannot tolerate a more ordinary environment. To the extent they are authentic hermits I think just the opposite is true; they see and hear God everywhere and locate the Divine presence in almost every conversation or relationship even when that presence is not made explicit. After all, the Incarnation reveals how profoundly the ordinary belongs to and mediates the extraordinary reality we call God. Hermits should be capable of perceiving this Presence even in obscurity and profound brokenness.

If someone you read claims to be a hermit and said they would only talk about spiritual things with relatives or friends I would suggest the following are true: 1) they are not truly a hermit -- though they may well be an isolated individual playing at being a hermit, 2) they are not possessed of a genuine or at least a mature spirituality, and 3) they are not particularly loving or open in the way they relate to others! Imagine demanding relatives and friends only talk about football, or politics because those dominate your life, or, more specifically, that they never mention the things which really move or excite or concern them because it does not fall within your own narrowly defined "spiritual" bailiwick? This demand limiting what folks can talk about with one is a false attempt to control reality while pointing to one's own supposed "spiritual status" or expertise; it is an implicit and illicit judgment on those whose spirituality may actually be more wholesome and integral than one's own. It certainly seems less pharisaical than a supposed "hermit" who can tolerate nothing but specifically "spiritual" conversation. Hermits live in and towards the silence of solitude but they are not hot house plants that cannot tolerate a more ordinary environment. To the extent they are authentic hermits I think just the opposite is true; they see and hear God everywhere and locate the Divine presence in almost every conversation or relationship even when that presence is not made explicit. After all, the Incarnation reveals how profoundly the ordinary belongs to and mediates the extraordinary reality we call God. Hermits should be capable of perceiving this Presence even in obscurity and profound brokenness.

One of the things we grow in as we grow spiritually is in our sense of how profoundly like as well as unlike others we are. Though our lifestyles, life experiences, and vocations may differ one from another, we come to see that we have the same yearnings, dreams, desires, needs, failings, limitations, potentials, etc., as the persons all around us. We also come to be able to hear the deep questions, concerns, and doubts, and perceive the transcendent potential living deep within each person. In all of this are the roots of authentic spirituality and a compassion and love which marks such a spirituality. None of these need be dressed up in pious language --- though sometimes specifically theological language can be helpful in expressing these deep realities. Still, the authentically spiritual is profoundly human just as it is profoundly divine.

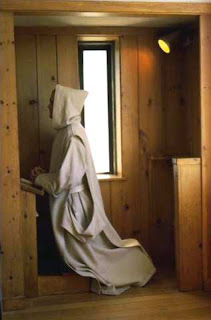

Thus, it seems to me that a hermit should certainly be able to negotiate the real world without the compartmentalization described in your question or a similar fragmentation which seems to me to be more typical of sinfulness (alienation) than human wholeness and relatedness! After all, eremitical life humanizes us; it strips us of pretense and allows us to stand secure as our truest selves in the love of God. If a "hermit" cannot relate to others without the pious role-playing described in your question, then better she have nothing to do with family and friends! If she cannot relate to them in genuine love, sincere interest, empathy, and compassion without playing a role or donning some sort of silly stereotype as the "character" friends and family are supposed to indulge, then she had best stay in her "hermitage" without contact with others --- and I say this not only for the sake of these same others, but for the sake of the eremitical vocation this "hermit" claims to represent!

|

| Sister Rachel Denton, Er Dio |

I hope this is helpful. It's clearly something I feel passionately about!