Today is the feast day of Maximillian Kolbe who died on this day in Auschwitz after two months there, and two weeks in the bunker of death-by-starvation. Kolbe had offered to take the place of a prisoner selected for starvation in reprisal when another prisoner was found missing and thought to have escaped. The Kommandant, taken aback by Kolbe's dignity, and perhaps by the unprecedented humanity being shown, stepped back and then granted the request. Father Maximillian sustained his fellow prisoners and assisted them in their dying. He was one of four remaining prisoners who were murdered by an injection of Carbolic Acid when the Nazi's deemed their death by starvation was taking too long. When the bunker was visited by a secretary-interpreter immediately after the injections, he found the three other prisoners lying on the ground, begrimed and showing the ravages of the suffering they had undergone. Maximillian Kolbe sat against the wall, his face serene and radiant. Unlike the others he was clean and bright.

Today is the feast day of Maximillian Kolbe who died on this day in Auschwitz after two months there, and two weeks in the bunker of death-by-starvation. Kolbe had offered to take the place of a prisoner selected for starvation in reprisal when another prisoner was found missing and thought to have escaped. The Kommandant, taken aback by Kolbe's dignity, and perhaps by the unprecedented humanity being shown, stepped back and then granted the request. Father Maximillian sustained his fellow prisoners and assisted them in their dying. He was one of four remaining prisoners who were murdered by an injection of Carbolic Acid when the Nazi's deemed their death by starvation was taking too long. When the bunker was visited by a secretary-interpreter immediately after the injections, he found the three other prisoners lying on the ground, begrimed and showing the ravages of the suffering they had undergone. Maximillian Kolbe sat against the wall, his face serene and radiant. Unlike the others he was clean and bright.14 August 2019

Feast of Saint Maximillian Kolbe (reprised)

Today is the feast day of Maximillian Kolbe who died on this day in Auschwitz after two months there, and two weeks in the bunker of death-by-starvation. Kolbe had offered to take the place of a prisoner selected for starvation in reprisal when another prisoner was found missing and thought to have escaped. The Kommandant, taken aback by Kolbe's dignity, and perhaps by the unprecedented humanity being shown, stepped back and then granted the request. Father Maximillian sustained his fellow prisoners and assisted them in their dying. He was one of four remaining prisoners who were murdered by an injection of Carbolic Acid when the Nazi's deemed their death by starvation was taking too long. When the bunker was visited by a secretary-interpreter immediately after the injections, he found the three other prisoners lying on the ground, begrimed and showing the ravages of the suffering they had undergone. Maximillian Kolbe sat against the wall, his face serene and radiant. Unlike the others he was clean and bright.

Today is the feast day of Maximillian Kolbe who died on this day in Auschwitz after two months there, and two weeks in the bunker of death-by-starvation. Kolbe had offered to take the place of a prisoner selected for starvation in reprisal when another prisoner was found missing and thought to have escaped. The Kommandant, taken aback by Kolbe's dignity, and perhaps by the unprecedented humanity being shown, stepped back and then granted the request. Father Maximillian sustained his fellow prisoners and assisted them in their dying. He was one of four remaining prisoners who were murdered by an injection of Carbolic Acid when the Nazi's deemed their death by starvation was taking too long. When the bunker was visited by a secretary-interpreter immediately after the injections, he found the three other prisoners lying on the ground, begrimed and showing the ravages of the suffering they had undergone. Maximillian Kolbe sat against the wall, his face serene and radiant. Unlike the others he was clean and bright.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:39 AM

![]()

![]()

13 August 2019

Discerning an Eremitical Vocation

[[ Dear Sister, I’m writing to ask you specifically how one

discerns a call to the eremitic life? Are there things one discerns alone and

others one discerns with someone from the diocese?]]

[[ Dear Sister, I’m writing to ask you specifically how one

discerns a call to the eremitic life? Are there things one discerns alone and

others one discerns with someone from the diocese?]]

Thanks for your questions. Let me be more general before getting truly specific. One discerns an eremitical life in the same way one discerns any other vocational path: one evaluates what is happening inside one which seems to call him/her for this particular pathway to 1) contemplative prayer, 2) then to contemplative life itself, 3) and then then to a life of even greater silence, solitude and stricter separation from the world we know as the eremitical life. Beyond this, if one decides one is called to the eremitical life described generally in step three, one will discern which type of eremitical life to which one is called. (These include canonical or consecrated forms with public vows, both solitary eremitical life under c 603, semi-eremitical life in a community of hermits, as well as the possibility of a laura or colony of hermits, and 2) non-canonical forms with no vows or private vows, also known as lay hermits for non-clerics. Lay hermits can also live as solitary hermits or members of a laura or colony of hermits. More below.)

When one reaches the final stage mentioned above (what form of eremitical life?) one may understand oneself as a hermit in an essential sense but not necessarily in a formal sense; one needs to determine the more "formal" context required to be the hermit one is called by God to be. For instance, one will need to discern if one will do this in the lay state or the consecrated state of life. If one feels one might be called to the latter s/he will need to explore profession under canon 603 or life in an eremitical or semi-eremitical community or "institute of consecrated life". It is at this point, whether with a diocese or in the community, that one will need to engage in a mutual discernment process. If one does not wish to explore canonical (that is, a publicly committed or consecrated) life as a hermit, then there is no reason to consult with one's diocese. If one determines one is called to live eremitical life in the lay state (i.e., as a lay person acting in and from the rights and obligations of baptism alone), then one can freely do that without any further permission, admission by the Church to profession or consecration, etc. If, however, one believes one's vocation will be fulfilled as an ecclesial vocation or, that is, that one is called to live as a hermit in the consecrated state, then one must engage in this process of mutual discernment.

Clearly this process takes time. It takes time (usually at least a couple of years) to move from a more typical prayer life to contemplative prayer as a regular practice and then from contemplative prayer itself to a truly contemplative life (again, several years is typically required for this transition). It takes time living this and building in the degree of silence and solitude needed for it before one determines a genuine need for greater silence and solitude; and it takes time (once again, several years is typical here) before one can evaluate all of this and determine one is being called to what the Church recognizes as appropriate to and characteristic of eremitical silence and solitude or, as I have often written here, to a life where the silence of solitude is not only the environment in which one's life in wholeness best grows, but is also the goal of one's life and the gift quality (charism) one will bring to the Church and world with or through one's life.

Generally speaking, one's spiritual director can assist one in all of the steps or stages mentioned here. This is true especially with the specific pieces of adaptation and discernment involved in each step/stage. A director would be able to help the directee or client explore how the various elements of eremitical life "fit" with his/her call to human wholeness and holiness. In the third stage a director can help the person to explore the nature of and reasons for their needs for increased silence and solitude. Not all needs or reasons for these indicate a call to eremitical life and some can be unhealthy or at least unworthy of being chosen; these indicate the need for other kinds of adaptations or changes. When this is the case needs for greater silence or solitude are very unlikely to be indicators of a call to eremitical life. Meanwhile, if you want to bring additional questions, especially given how general I have been here, I will always be happy to answer them.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:25 PM

![]()

![]()

11 August 2019

On Canon 603 and the Chronically Ill and Disabled (follow-up questions)

[[Dear Sister, I have been interested in an article you wrote several years ago about eremitical life as a possible vocation for those who are chronically ill. Do dioceses consider that article when they are discerning whether or not to profess someone as a diocesan hermit? What about canon law that argues that candidates for religious life and priesthood must be in good health? Doesn't what you wrote conflict with these canons or do dioceses determine things on a case-by-case basis? I would think it might be a problem for dioceses to have writers like you seeing canon 603 as a kind of "haven" for those with mental and physical illnesses, wouldn't it? . . . Has anyone ever suggested your article makes it hard for dioceses considering canon 603 vocations?.... Has anyone suggested you are giving false hope to those who are disabled and expect to be admitted to profession when dioceses are really more likely to reject them?]]

[[Dear Sister, I have been interested in an article you wrote several years ago about eremitical life as a possible vocation for those who are chronically ill. Do dioceses consider that article when they are discerning whether or not to profess someone as a diocesan hermit? What about canon law that argues that candidates for religious life and priesthood must be in good health? Doesn't what you wrote conflict with these canons or do dioceses determine things on a case-by-case basis? I would think it might be a problem for dioceses to have writers like you seeing canon 603 as a kind of "haven" for those with mental and physical illnesses, wouldn't it? . . . Has anyone ever suggested your article makes it hard for dioceses considering canon 603 vocations?.... Has anyone suggested you are giving false hope to those who are disabled and expect to be admitted to profession when dioceses are really more likely to reject them?]]

Wow, good and difficult questions in some ways. Let me give them a shot! First of all, I have no idea if dioceses consider the article I wrote 30 years ago for Review for Religious (cf RFR archives: Volume 48, Number 2, March/April 1989). Certainly, there are copies out and about regarding this even though RFR is no longer, being published; also, I have posted a copy of it here on this blog ( cf, Review For Religious, Chronic Illness as Vocation and Possible Eremitical Vocation) as well as answered questions about it as follow-up. However, I really cannot say how widely read or influential the article is or has been over the years. On the other hand, I hope that at least some dioceses, pastors, and spiritual directors have read and considered the article and that they bear it in mind as they consider candidates for public profession under c 603 or work with those who are chronically ill. Chronic illness prevents many of us from living in community and sometimes (I don't know how often) it may condition us in ways which predispose towards lives of the silence of solitude -- lives in which the isolation occasioned by chronic illness can be redeemed and transfigured into the silence of solitude associated with eremitical life. Dioceses must be able to recognize this dynamic at work in the lives of the chronically ill when it occurs and, when circumstances are right (meaning when many more circumstances than illness per se come together in the relatively clear pattern of a healthy and graced eremitical calling), they must be open to admitting such persons to profession and consecration under canon 603.

Wow, good and difficult questions in some ways. Let me give them a shot! First of all, I have no idea if dioceses consider the article I wrote 30 years ago for Review for Religious (cf RFR archives: Volume 48, Number 2, March/April 1989). Certainly, there are copies out and about regarding this even though RFR is no longer, being published; also, I have posted a copy of it here on this blog ( cf, Review For Religious, Chronic Illness as Vocation and Possible Eremitical Vocation) as well as answered questions about it as follow-up. However, I really cannot say how widely read or influential the article is or has been over the years. On the other hand, I hope that at least some dioceses, pastors, and spiritual directors have read and considered the article and that they bear it in mind as they consider candidates for public profession under c 603 or work with those who are chronically ill. Chronic illness prevents many of us from living in community and sometimes (I don't know how often) it may condition us in ways which predispose towards lives of the silence of solitude -- lives in which the isolation occasioned by chronic illness can be redeemed and transfigured into the silence of solitude associated with eremitical life. Dioceses must be able to recognize this dynamic at work in the lives of the chronically ill when it occurs and, when circumstances are right (meaning when many more circumstances than illness per se come together in the relatively clear pattern of a healthy and graced eremitical calling), they must be open to admitting such persons to profession and consecration under canon 603.

I wrote the article you mentioned because I had come to understand that while I could not live religious life in community (my illness was both too demanding and too disruptive --- though initially we had not thought this would be the case), I could certainly live as a hermit. In fact, I came to understand that the context of eremitical silence and solitude could allow my own life in and with Christ to transform weakness and brokenness into a source and form of strength and essential wellness. I knew Paul's theology, "My grace is sufficient for you, my power is made perfect in weakness," and it seemed to fit the situation perfectly. At the same time, while illness and the isolation it occasioned was one predisposing condition for a life of eremitical solitude, it was not enough of itself to suggest, much less indicate I had an eremitical vocation. On the contrary, it might have suggested that physical isolation was a component of something pathological that must be countered, not given the chance to be transfigured into eremitical solitude via even greater silence and physical separation from others. For that reason, when I wrote the article in RFR I was very careful to indicate chronic illness was something which might indicate such a vocation; it was a possibility dioceses and spiritual directors should consider as they worked with those who were chronically ill or disabled.

No one has ever suggested my article makes it hard for dioceses trying to discern c 603 vocations, though I admit I hoped when I wrote it to introduce a possibility into their discernment processes they might not have considered adequately, namely, that chronic illness might be a source of the grace of an eremitical vocation which itself could contribute to eremitical formation in terms of several different and critical values (pilgrimage, solitude vs isolation, an independence rooted in radical dependence upon God, a paradoxical wholeness, etc). That was completely contrary to the wisdom of the time re religious vocations; but then canon 603 itself was also pretty contrary to what we were used to at that time as well! Again, my article did not argue that chronic illness is a kind of passport to profession. I did not say that illness provides sufficient grounds for professing someone or discerning eremitical vocations; it argued that in some cases there was the possibility that illness might condition one towards such a vocation, might make it easier for such a vocation to be received. At the same time then, I have not heard anyone suggest I am giving folks false hope. I have been clear that discerning an eremitical vocation takes time and serious attention and prayer; I know that some dioceses may not consider chronic illness in the way I would hope they would, but at the same time I think dioceses in general do recognize the flexibility and freedom built into canon 603 even while they recognize the demanding nature of the life codified there.

No one has ever suggested my article makes it hard for dioceses trying to discern c 603 vocations, though I admit I hoped when I wrote it to introduce a possibility into their discernment processes they might not have considered adequately, namely, that chronic illness might be a source of the grace of an eremitical vocation which itself could contribute to eremitical formation in terms of several different and critical values (pilgrimage, solitude vs isolation, an independence rooted in radical dependence upon God, a paradoxical wholeness, etc). That was completely contrary to the wisdom of the time re religious vocations; but then canon 603 itself was also pretty contrary to what we were used to at that time as well! Again, my article did not argue that chronic illness is a kind of passport to profession. I did not say that illness provides sufficient grounds for professing someone or discerning eremitical vocations; it argued that in some cases there was the possibility that illness might condition one towards such a vocation, might make it easier for such a vocation to be received. At the same time then, I have not heard anyone suggest I am giving folks false hope. I have been clear that discerning an eremitical vocation takes time and serious attention and prayer; I know that some dioceses may not consider chronic illness in the way I would hope they would, but at the same time I think dioceses in general do recognize the flexibility and freedom built into canon 603 even while they recognize the demanding nature of the life codified there.It is the case that I hear occasionally from someone who is chronically ill or disabled and who read my article all those years ago (or more recently for that matter!) and have subsequently been profoundly disappointed by a diocese who will not admit them to profession. Those communications are some of the most difficult I receive; they cause me pain because my article did have a place in encouraging their imagination about and discernment of a vocation; I feel particularly sorry for the individuals involved and empathize with their disappointment. The difficulty of balancing the nature of a public vocation (consecrated life is always a matter of public commitments and obligations) and discerning a call in someone whose life does not fit all the standard criteria or who embody the grace of God in a new and unexpected way, is very difficult for dioceses as well as for the individuals petitioning for admission to profession and consecration. Sometimes the answer is living eremitical life with a private commitment rather than as a consecrated hermit or anchorite. Sometimes the person needs to transition from the isolation occasioned by their illness to solitude-as-healing, and then to life in society. Sometimes (especially in these kinds of cases I think) both the individual and the diocese need to take more time together in their discernment. Canon 603, because it does not codify any specific time frames, certainly allows for this kind of time if dioceses take both its traditional elements and its uniqueness seriously.

What must be certain is that the person advanced to profession (public vows) and eventually to consecration can live c 603 in an exemplary (that is, an edifying) way which helps dispel the stereotypes which so accrued to eremitical life throughout history. This person MUST say to the whole Church that eremitical solitude is not about isolation but is instead about the redemption of isolation into a unique and often obscure but very real form of community lived in and with Christ for the sake of others. This is why I have written those admitted to profession must have experienced eremitical solitude as redemptive and be able to witness to that clearly with their lives. The witness given depends upon the authenticity and depth of the hermit's experience and ecclesial rootedness. This presence of a redemptive element is something I have put forward as a central element in discerning an eremitical vocation under c 603 and it is something I am more clear about now than when I first affirmed it. Still, if dioceses are to demand the presence of such an element they also MUST, for their part, be open to discerning its presence which builds on chronic illness and/or disability. The process leading to c 603 profession and consecration is meant be truly mutual.

What must be certain is that the person advanced to profession (public vows) and eventually to consecration can live c 603 in an exemplary (that is, an edifying) way which helps dispel the stereotypes which so accrued to eremitical life throughout history. This person MUST say to the whole Church that eremitical solitude is not about isolation but is instead about the redemption of isolation into a unique and often obscure but very real form of community lived in and with Christ for the sake of others. This is why I have written those admitted to profession must have experienced eremitical solitude as redemptive and be able to witness to that clearly with their lives. The witness given depends upon the authenticity and depth of the hermit's experience and ecclesial rootedness. This presence of a redemptive element is something I have put forward as a central element in discerning an eremitical vocation under c 603 and it is something I am more clear about now than when I first affirmed it. Still, if dioceses are to demand the presence of such an element they also MUST, for their part, be open to discerning its presence which builds on chronic illness and/or disability. The process leading to c 603 profession and consecration is meant be truly mutual.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:45 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: chronic illness and disability as vocation, chronic illness and eremitical life, disability as vocation, discernment of eremitical vocations, Silence as Redemptive, Validation vs redemption of Isolation

09 August 2019

Feast of Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

At today's service I read the Gospel from today's daily readings. It was the very familiar, " Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me." (Matt 16:24-28). It was not the optional readings for the Feast but certainly suited the day given who Sister Teresa Benedicta was and is. I think it is easy for us to think of taking up our crosses as an exhortation simply to embrace suffering. It certainly means that but it means more besides, namely, it calls us to grow in what some call cruciformity as we adopt an attitude of vulnerability and love towards all we meet in our world. It asks that we open ours arms and our hearts to embrace those we meet with the love of God that empowers us. In short we allow the love of and our love for others to shape us in a cruciform way. Two elements brought this home to me this week besides the fact of our Feast.

At today's service I read the Gospel from today's daily readings. It was the very familiar, " Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me." (Matt 16:24-28). It was not the optional readings for the Feast but certainly suited the day given who Sister Teresa Benedicta was and is. I think it is easy for us to think of taking up our crosses as an exhortation simply to embrace suffering. It certainly means that but it means more besides, namely, it calls us to grow in what some call cruciformity as we adopt an attitude of vulnerability and love towards all we meet in our world. It asks that we open ours arms and our hearts to embrace those we meet with the love of God that empowers us. In short we allow the love of and our love for others to shape us in a cruciform way. Two elements brought this home to me this week besides the fact of our Feast.

Last week and this I reread several novels by Chaim Potok. One of these was My Name is Asher Lev. Asher Lev is a Hasidic Jew growing up in the earlier to mid 1900's. His devoutly religious family are Ladover Hasidim who seek to counter the murderous anti-Semitism so prevalent in Europe in the 1930's and 1940's by establishing Ladover communities, synagogues and yeshivas. They have lost dearly-loved relatives in pogroms and the holocaust and have heard again and again that anti-Semitism is a justifiable result of the supposed fact that "It was Jews that killed Jesus". (It must be said that this is an undeniable, and unutterably shameful piece of our Christian history which has blasphemously victimized the innocent in the name of the greatest act of selfless love we know.) So these people too are marked by the Cross of Christ; it is linked for them to the senseless and hate-filled deaths of brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, aunts, uncles, and cousins --- and yet, at great risk to himself Asher's father travels in faithfulness to the Master of the Universe to support Jews and extend Ladover Hasidism throughout Europe.

That is one part of the story. The other is that Asher Lev has a prodigious gift; he is an artist, a young man with an irresistible and insatiable desire/need to draw and paint. As he grows up in this fundamentalist Ladover community, his family is torn between dealing with Asher's gift (which, his father, especially, thinks is demonic in origin) and the desire to honor one another and Ladover Hasidism. Asher's Mother stands torn between her love for her Son and his gift, her love for her husband, her God and the Ladover tradition; she is a buffer for everyone's pain.

Eventually Asher is led to paint the story of his family's anguish. When Asher's Father travels Rivkeh, his wife, waits for his return and stands looking out the living room window, sometimes for hours; this becomes the basis for Asher's greatest paintings, two crucifixions. Each has his Mother framed in the living room window, tied there with the ties from the venetian blinds and stretched between her husband returning from his travels and her son (whose paint brush represents a spear which penetrates her heart). All are held together by love, but of course it is not an easy thing. It is an anguished, tortured love. Asher has drawn on crucifixion because it is the only aesthetic frame he knows as an artist which is sufficient to "hold" and express the torment, pain, and passion of his life. His family are bewildered by his art, offended, betrayed, torn by his gift and profoundly saddened by the way in which Asher has hurt them with it. Asher is exiled from the Brooklyn Ladover community. Cruciformity marks every life in this story. As Christians we know the profound anguish and today, to a lesser degree, the offense of the cross but for us it has primary notes of joy and triumph as well.

The second element which brought this dimension home to me especially was the fact that this is August, the month associated with entrance to religious life for many of us, the month of professions and jubilees, the month when we celebrate the commitments we and our Brothers and Sisters have made to life in Christ. It is the month when the appropriate refrain I have heard several times is: He is faithful and so are we!! This year is my pastor's 50th jubilee and I entered 50 years ago this month as well. All over the world stories of jubilees are shared: one I heard was about an IHM Sister who is 102 yo and celebrated her 85th jubilee last week; she processed into liturgy determined to walk the distance on her own two feet. She did it and was joyful and triumphant when she reached the altar as were those celebrating with her. This too was a symbol of her long and faithfully-formed cruciform life. Another Jubilarian at the same liturgy processed in with her niece, a young Sister who had just made her first profession. The two walked in hand in hand, the younger supporting the elder, both radiant with joy. When I shared this story with another Sister I was reminded then of a Franciscan from her congregation who died at 107 yo and who also celebrated 85 years of religious life; her niece is also a Franciscan (same congregation) and is alive, though quite elderly, today. Stories of lives dedicated to Christ and shaped over years in vulnerability to and in the service of Incarnate Love. Cruciformity. The shape of the faithful, sometimes anguished, joy-filled and persevering discipleship Jesus calls each of us to today.

The third element, of course, the element which brings all of this together for me, is the life and witness of St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross whose feast we celebrate today. Edith Stein was a brilliant Jewish philosopher who studied for her doctorate under Edmund Hussurl. As a youth she ceased believing in God but as a young adult she read St Teresa of Avila's autobiography and recognized it as truth. She became Catholic. As her life experience and spirituality broadened she wrote a dissertation on Empathy. Prevented from taking a professorship first because she was a woman, and later because of her Jewishness, she continued her reading in philosophy and theology and eventually became a Carmelite Nun. At the center of her life was the cross; she called it "our only hope". Sister Teresa Benedicta's last significant work was on St John of the Cross.

The third element, of course, the element which brings all of this together for me, is the life and witness of St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross whose feast we celebrate today. Edith Stein was a brilliant Jewish philosopher who studied for her doctorate under Edmund Hussurl. As a youth she ceased believing in God but as a young adult she read St Teresa of Avila's autobiography and recognized it as truth. She became Catholic. As her life experience and spirituality broadened she wrote a dissertation on Empathy. Prevented from taking a professorship first because she was a woman, and later because of her Jewishness, she continued her reading in philosophy and theology and eventually became a Carmelite Nun. At the center of her life was the cross; she called it "our only hope". Sister Teresa Benedicta's last significant work was on St John of the Cross.

That same year, on 02 August 1942, the Gestapo came to her convent to arrest Sister Teresa and her blood sister, Rosa, also a Catholic who served at the convent. They were moved to a transit camp, Westerborc, and on 07. August, were transported to Auschwitz. She and Rosa were gassed there two days later on 09. August. 1942. As she left the convent with her sister, she said, [[Come, we are going for our people.]] Meanwhile, a good friend said of Edith: [[She is a witness to God's presence in a world where God is absent.]] In the seemingly godless world of Nazi death camps, in the face of meaningless slaughter Sister Teresa Benedicta showed others the face of Love incarnate. Cruciformity, Jesus' call to embrace the cross with our lives was modeled by Edith Stein as John Paul II noted at her canonization, a "daughter of Israel" and a "daughter of Carmel."

Whether in anguish, joy, triumph, or all three at once and more besides --- we celebrate that we and our Brothers and Sisters in Christ are called to embrace a life of vulnerability and love empowered by our trust in the God who will be there both for and with us in the unexpected and even the unacceptable place. That is what it means to take up our cross, to live truly in Christ. We are not victims but victors in him for the sake of creation. This is the shape of discipleship and all authentic humanity --- a life of transforming generosity, where self-centeredness is replaced by self-emptying, and our hearts are opened to others in compassion; a life of cruciformity.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:26 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Cruciformity, Edith Stein, Sister Teresa Benedicta, Theology of the Cross

07 August 2019

Jesus and the Canaanite Woman

If we're looking for a Gospel lection that breaks all stereotypes today's is one of these! This reading is sometimes categorized among the "difficult sayings of Jesus" because it has Jesus characterizing a Gentile woman as a dog (a typical epithet of his day when referring to Gentiles) and refusing to extend healing to her daughter because HIS mission is first of all to the lost of Israel, not to the Gentiles. And so, the woman, who has already silenced Jesus with a terrific act of faith, "Have pity on me, Lord, Son of David," answers Jesus' instruction on this point with a bit of instruction of her own: [[ Yes, but even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from the Master's table!]] Jesus, already silenced and now thoughtful, seems even to reconsider and expand the scope of his own ministry in light of it. If Jesus' can grow in grace and stature in this way, through the mediation of a completely disenfranchised woman, then is anyone in the Church really beyond being instructed by the women standing (at best) on the margins of power and authority or the Christ standing as their Master? I don't think so.

If we're looking for a Gospel lection that breaks all stereotypes today's is one of these! This reading is sometimes categorized among the "difficult sayings of Jesus" because it has Jesus characterizing a Gentile woman as a dog (a typical epithet of his day when referring to Gentiles) and refusing to extend healing to her daughter because HIS mission is first of all to the lost of Israel, not to the Gentiles. And so, the woman, who has already silenced Jesus with a terrific act of faith, "Have pity on me, Lord, Son of David," answers Jesus' instruction on this point with a bit of instruction of her own: [[ Yes, but even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from the Master's table!]] Jesus, already silenced and now thoughtful, seems even to reconsider and expand the scope of his own ministry in light of it. If Jesus' can grow in grace and stature in this way, through the mediation of a completely disenfranchised woman, then is anyone in the Church really beyond being instructed by the women standing (at best) on the margins of power and authority or the Christ standing as their Master? I don't think so.But Jesus' example condemns such an approach. In this lection one of the lowest and the least becomes the One by which Jesus truly hears the voice of his Father and comes to modify his own understanding of his mission. After his silence at her first words to him Jesus rehearses the standard Jewish arguments for her and for his disciples, arguments that make sense in THIS worldly terms and in terms of an Israel threatened by outsiders, but not in terms of the Kingdom of God: "I was sent only to the children of Israel; It is not just (right or fair) to take the food from the children (Israel) and throw it to the dogs (Gentiles)." (We might hear common arguments for excluding folks from Eucharist today --- arguments that make good sense in worldly terms: "We cannot pretend there is a unity that doesn't really exist. We cannot defile the Eucharist by giving it to public and obstinate sinners. It wouldn't be just to do these things!") But in Matthew's telling of the Gospel story, Jesus has already fed the five thousand (apparently mainly Jews) and found there was plenty left over. He has also just preached that it is what comes out of us that defiles, but to eat with unwashed hands does NOT defile. . . The Canaanite women's response is a reminder of Jesus' great Eucharistic miracle as well as the infinite value and power to heal of even the smallest crumb that comes to the most unworthy from God.

But it reminds us of much more as well. For those, for instance, who object that women cannot teach, we have an example of a Gentile woman teaching Jesus about the will of God and helping to reshape his mission. In so doing she reminds Jesus of a different "justice" in which all are therefore welcome at Christ's table; similarly she reveals that the way Israel is first may not be precisely the way the world (or Israel herself) sees or has seen such matters. Israel is to be first in including, ministering to, and serving the outsider and the unworthy, not in excluding them until some other day of the Lord is at hand. That day is here, NOW, and, with the Canaanite woman's intervention, Jesus too comes to see this more clearly and embrace it more fully. In some ways this shift in vision, a shift the Church herself is called upon to make, parallels the two different ways we have of understanding the term Catholic: the Latin sense of universalis which means universal and draws a huge circle representing the universal but inevitably leaves some outside the circle however large it is drawn, and the Greek sense of Katholicos which is universal in the sense of leaven in bread where no one and nothing is left excluded or untouched, unchanged, and no one is left unfed.

But it reminds us of much more as well. For those, for instance, who object that women cannot teach, we have an example of a Gentile woman teaching Jesus about the will of God and helping to reshape his mission. In so doing she reminds Jesus of a different "justice" in which all are therefore welcome at Christ's table; similarly she reveals that the way Israel is first may not be precisely the way the world (or Israel herself) sees or has seen such matters. Israel is to be first in including, ministering to, and serving the outsider and the unworthy, not in excluding them until some other day of the Lord is at hand. That day is here, NOW, and, with the Canaanite woman's intervention, Jesus too comes to see this more clearly and embrace it more fully. In some ways this shift in vision, a shift the Church herself is called upon to make, parallels the two different ways we have of understanding the term Catholic: the Latin sense of universalis which means universal and draws a huge circle representing the universal but inevitably leaves some outside the circle however large it is drawn, and the Greek sense of Katholicos which is universal in the sense of leaven in bread where no one and nothing is left excluded or untouched, unchanged, and no one is left unfed. So, through the intervention of the faith of a woman and "outsider" or alien, Jesus' understanding of God's will and perhaps too, the nature of the People of God continues to grow; Jesus continues to grow in grace and stature. A couple of years ago a friend gave me a card which read, Ït takes courage to grow up and become who you are called to be." So it was for Jesus; so it is for each of us. When we muster even the smallest bit of faith or courage we will be astounded at what comes from the seeds we plant. This courage and openness to growing is called obedience. But we must speak our own truth, more and more truly, more and more courageously. Only in this way will our church and world become the realities God calls them to be.

So, through the intervention of the faith of a woman and "outsider" or alien, Jesus' understanding of God's will and perhaps too, the nature of the People of God continues to grow; Jesus continues to grow in grace and stature. A couple of years ago a friend gave me a card which read, Ït takes courage to grow up and become who you are called to be." So it was for Jesus; so it is for each of us. When we muster even the smallest bit of faith or courage we will be astounded at what comes from the seeds we plant. This courage and openness to growing is called obedience. But we must speak our own truth, more and more truly, more and more courageously. Only in this way will our church and world become the realities God calls them to be.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

9:55 AM

![]()

![]()

06 August 2019

Feast of the Transfiguration (Reprised)

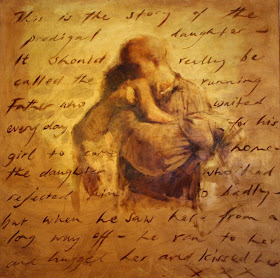

Transfiguration by Lewis Bowman

|

(N.B. the Transfiguration story today is taken from Luke's gospel but my remarks which are reprised below depend on Matthew's version.) It is in the face of these situations that we hear today's Gospel of the Transfiguration. Jesus takes Peter, James, and John up on a mountain apart. He takes them away from the world they know (or believe they know) so well, away from peers, away from their ordinary perspective, and he invites them to see who he really is. In the Gospel of Luke Jesus' is at prayer --- attending to the most fundamental relationship of his life --- when the Transfiguration occurs. Matthew does not structure his account in the same way. Instead he shows Jesus as the one whose life is a profound dialogue with God's law and prophets, who is in fact the culmination and fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets, the culmination of the Divine-Human dialogue we call covenant. He is God-with-us in the unexpected and even unacceptable place. This is what the disciples see --- not so much a foretelling of Jesus' future glory as the reality which stands right in front of them --- if only they had the eyes to see.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

9:30 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Feast of the Transfiguration

03 August 2019

Follow-up on Why Canon 603?

[[ Dear Sister, thank you for answering my question on Canon 603. I had read the following passage which seems to disagree with some of what you wrote: "What was it that made people, possibly hermits themselves, in the early 1980's, entreat a Church law to designate and recognize a category? That was an interesting decade following upon two previous interesting decades. Laws are made to stop abuses or to introduce something that people want." Could you clarify whether it was to curb abuses or to beg for something hermits wanted that caused the Church to create canon 603? Also, did this entreaty happen in the 1980's or at another time?]]

[[ Dear Sister, thank you for answering my question on Canon 603. I had read the following passage which seems to disagree with some of what you wrote: "What was it that made people, possibly hermits themselves, in the early 1980's, entreat a Church law to designate and recognize a category? That was an interesting decade following upon two previous interesting decades. Laws are made to stop abuses or to introduce something that people want." Could you clarify whether it was to curb abuses or to beg for something hermits wanted that caused the Church to create canon 603? Also, did this entreaty happen in the 1980's or at another time?]]

Thank you for continuing the discussion. I'm not sure where you locate the disagreement. However, to be clear, I don't know if the hermits under Bishop de Roo's protection asked him to intervene at Vatican II, but it would make sense if their discussions with him --- especially in light of the anguish they had had to go through in order to leave their monasteries and establish themselves as hermits apart from monastic life --- had included the possibility of a genuine appreciation of the eremitical life by the universal Church. Even so, the intervention at Vatican II occurred in the mid- sixties, not in the 1980's and was informed primarily by Bishop de Roo's appreciation of the eremitical life as he came to know it through a dozen or so hermits living in a laura in British Columbia. Neither can just anyone in the Church simply ask in an effective way for the Church hierarchy to create a law/canon.

Again, Bp de Roo's intervention listed at least a half dozen reasons for recognizing the eremitical life as a gift of God to the Church with significant prophetic and evangelical elements. He did not, so far as I can find, speak of abuses of eremitical life, nor would he have asked for recognition for a vocation for such a reason. It is far more effective to allow a lifestyle to remain unrecognized and thus too, relatively unknown if one wants to deal with abuses. Further, the solitary eremitical life had largely died out in the Western Church; again, abuses were not an issue until after canon 603 was promulgated and at that point they became an issue mainly for dioceses and candidates who did not really understand the distinction between a lone individual and a hermit. From the failure to draw this significant distinction come instances of inauthentic "hermits" and premature or unwise professions which do not last or edify. Such unwise and premature professions also lead to a fundamental distrust of the canon and the tendency of dioceses to refuse to profess even really strong candidates. (There is a refusal to truly discern vocations on a case-by-case basis; discernment is never entered into and the canon is dismissed as speaking of "stopgap" or "fallback" vocations rather than being recognized as creating the norm for authentic solitary eremitical life.)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:20 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Bishop Remi De Roo

31 July 2019

Why Canon 603?

[[ Dear Sister, is it true that Canon 603 was formulated or published in order to prevent abuses of eremitical life by hermits? Is Canon 603 important for other reasons than this? Also, has there been a history of problems with hermits and if so, why would the Church institutionalize such a vocation?]]

[[ Dear Sister, is it true that Canon 603 was formulated or published in order to prevent abuses of eremitical life by hermits? Is Canon 603 important for other reasons than this? Also, has there been a history of problems with hermits and if so, why would the Church institutionalize such a vocation?]]

Thanks for your questions. I have answered these in the past so let me refer you to past answers. One article you might find helpful in this regard is Fraudulent Hermits Throughout History from November 2015. This article notes there is a history in the Church of dealing with fraudulent hermits (though more fundamentally these were attempts to create norms for authentic eremitical life) and also outlines how canon 603 differs from these attempts, not only in scope but in nature and origin. There are earlier articles on the origin and history of canon 603 (cf label Canon 603 - history), most particularly which outline the positive reasons Bp Remi De Roo intervened at Vatican II in order to get the Church Fathers to recognize eremitical life as a "state of perfection" (a vocation to the consecrated state of life). (See especially, Followup on Visibility and Betrayal of Canon 603 for the first article I wrote here in which I remember listing the positive reasons given by Bishop De Roo.)

To answer your questions very briefly here, canon 603 was created because Bp Remi de Roo had experienced eremitical life as Bishop Protector of about a dozen hermits who had come together after leaving their solemn vows as monks. Their monasteries did not allow for eremitical life in their proper law so these monks had to leave their monasteries, their vows, and be secularized in order to pursue life as hermits. It was a big sacrifice but eventually they founded a laura and did so under Bp De Roo. He saw the significant contributions to the Church these vocations represented and wrote an intervention as Vatican II to support making this vocation part of those allowing for public profession and consecration. Almost 20 years later canon 603 was the result. Thirty-six years later c 603 is still a relatively unknown and less understood vocation.

I would argue the vocation is important for all the reasons Bp De Roo enumerated, but above all I would argue the vocation is important because it establishes solitude as antithetical to isolation or a selfish individualism; it also, therefore, gives an important example to isolated elderly and the chronically ill and disabled regarding the completion that is possible in God alone and so too, to the meaningfulness of any life rooted in God. Bp De Roo listed at least a half dozen positive reasons for the recognition of this vocation by the Church. Abuses, though sometimes problematical throughout the history of the vocation, were not listed as part of the origin of canon 603. The Church is not unaware of the problems with hermits in her history, but what is more compelling are the prophetic and witness values of this vocation. Hermits proclaim the Gospel of Christ with a peculiar vividness. As noted recently, in the lives of hermits we hear of (and see) a God whose power is perfected in weakness, who alone completes us in our authentic humanity, who loves us with an everlasting love, and who calls us to a radically countercultural life as Christians.

While we can't avoid speaking of the stereotypes, fraudulent versions, and distortions of eremitical life, the positive reasons for institutionalizing the vocation are much more important. At bottom the Church recognizes this life as a gift of God given/entrusted to the Church for her own life and edification.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:14 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Canon 603 - history

28 July 2019

Followup Question on Lay Hermits and Their Potential Capacity to Speak Better to the Laity

[[Hi Sister, I remember where you once said you were surprised to find that in some ways being a lay hermit might have been able to speak better to laity than being a consecrated hermit under c 603. I wondered if you could explain how it is this might be so.]]

[[Hi Sister, I remember where you once said you were surprised to find that in some ways being a lay hermit might have been able to speak better to laity than being a consecrated hermit under c 603. I wondered if you could explain how it is this might be so.]]

Good question and not one I can recall following up on before this. Thanks for asking. One of the problems we still deal with despite Vatican II is the sense many of the laity (in the vocational sense of that word) still seem to have is that a call to deep prayer lives and exhaustive holiness is somehow the purview of religious. That said it seems at least equally true that living such a life (of exhaustive holiness) but as a hermit, when it is considered at all, is considered the purview of religious. While many lay persons feel called to live lives of solitude and consider themselves to be hermits, the call to a life of "assiduous prayer and penance", stricter separation from the world, and "the silence of solitude" --- which is far more than a life of silence and solitude, still most often seems to be considered the purview of religious. A too-distinct line is drawn between the life of the religious and that of the lay person (using lay here in the vocational rather than hierarchical sense).

Eremitical life, as it is defined in c 603, then, is rightly seen as giving us a vocation which is vastly different than simply going off and living in silence and solitude, or even of loving solitude. Part 2 of the canon makes clear that a consecrated form of this life is lived by making a public commitment in the hands of one's local bishop. However, part 1 of the canon simply defines the nature of eremitical life per se as this is understood in the Roman Catholic Church. The problem is that very few lay persons I have read or spoken to seem to think Part 1 of canon 603 can describe a vocation suited to lay persons, because it specifically defines a desert vocation. Sometimes this becomes clearer as lay persons express comfort calling themselves solitaries or "lovers of solitude" but eschew the description hermit because they cannot see themselves embracing a desert spirituality; I have seen this reflected even in popular publications like Raven's Bread, a newsletter for hermits and other lovers of solitude.

A desert vocation is profoundly dependent upon God in the silence of solitude for one's completion as a human being; it is relatively and even absolutely rare for a person to be called to human wholeness in this way. As a result many lay persons embrace a less demanding form of life where some degree of prayer, silence, and solitude matches their temperaments, perhaps, but risking everything on the fulfillment which comes from a solitary relationship with God is simply not their desire or their actual vocation. The Episcopal Church recognizes solitaries who are not hermits --- vowed religious who are neither members of congregations or institutes of consecrated life nor who embrace a true desert vocation. Their lives, though of undoubted value, do not speak to others in the same way a hermit's might, nor do these people necessarily desire to live that same witness. Neither do those who choose to live a kind of "part-time" eremitism where solitude is a kind of luxury and assiduous prayer and penance are less ways of life than they are significant additions to one's way of life. (More about this another time, I think.)

And yet, it is my opinion that lay persons who do embrace all the elements of canon 603 apart from its Section 2 (the provision for public vows under the supervision of the diocesan bishop), and do live as hermits, also have the capacity to say to every person that we are called, without exception, to live the values of assiduous prayer lives with some degree of silence and solitude and an essential separation from the world (that is from that which is contrary to God or promises fulfillment apart from God). Moreover, these hermits can say to isolated elderly, and the chronically ill, that eremitical life itself (as described in canon 603) can be a perfect means of contextualizing their lives and serving others in an incredibly meaningful way, whether or not these persons experience a call to consecration under canon 603 --- and (perhaps especially) even if they do not precisely because they are less well recognized by the Church than are consecrated vocations. Again, the Church must do better in encouraging and recognizing lay vocations generally, but lay eremitical vocations specifically.

My point in the article you referred to was that, surprisingly, my very consecration separated me somewhat from those who neither seek nor are called to live as consecrated hermits and it may have made it harder for them to consider eremitical life as a vocation for lay persons. Given the importance of eremitical life as a particularly meaningful context and even a potential vocation which can assist isolated elderly and chronically ill (et al.) to appreciate the value of their lives when other standards (work, productivity, social activity, etc) fall away, I found this problematical. I wanted to witness to a way of life that allowed the chronically ill and isolated elderly to discover a new and marked value to their lives, particularly as a privileged way to proclaim the gospel of the God whose power is perfected in weakness. To find my own vocation was mainly seen as only appropriate for religious and was not considered as defining a life appropriate for lay persons (in the vocational, not hierarchical sense) was surprising and disappointing to me.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:28 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: importance of lay eremitical vocations, Lay hermits vs diocesan hermits

27 July 2019

On denying Chronic Illness in Order to be Admitted to Profession under Canon 603

[[Dear Sister, have you heard of dioceses that refuse to profess hermits because they have a chronic illness? I am concerned my diocese will not agree to profess me because I am chronically ill so I am thinking about not telling them about this until after profession.. What do you think of this idea?]]

[[Dear Sister, have you heard of dioceses that refuse to profess hermits because they have a chronic illness? I am concerned my diocese will not agree to profess me because I am chronically ill so I am thinking about not telling them about this until after profession.. What do you think of this idea?]]

Thank you for writing. I have to say frankly that I think this specific idea is really terrible. While I understand the fear you are experiencing, it makes no sense to approach your diocese with a petition to admit you to eremitical profession while considering withholding important (in this case critical) personal information from them. Canonically I believe your diocese could determine your profession to be invalid in such circumstances but I would need to check that out. (Addendum: see the following passage regarding malice in the making of a vow, The emboldened portion does indicate that a lie in a matter of external forum of the kind you are envisioning would lead to the invalidity of vows: [[Malice (dolus) in the context of this canon is the deliberate act of lying or of concealing the truth in order to get another person to make a vow which he or she would not do if the truth were known, or in order for oneself to get permission to make a vow, which would not be permitted if the truth were known. For example, a novice conceals from her superiors some external forum fact that, if known, would result in her not being admitted to profession of vows. Such malice invalidates the profession of vows (cf. C. 656, 4)]] I think a diocese could decide that they would have professed you in any case and not act on c 656.4, but the possibility of invalidating your vows clearly exists.

Canonical matters aside please consider the wisdom and import of approaching public profession while withholding such a significant piece of personal information. Your chronic illness is not something peripheral to your life, whether as a hermit or not, but central to it and to the witness you are called to give to the Gospel. Is there a dimension of your life which is not touched by your illness and its requirements? In light of this, how will you write a Rule of life that binds you in law if you do not include the fact of chronic illness? How will you be bound in obedience to legitimate superiors who do not know this important truth about you? (In this matter consider how they would exercise a ministry of authority --- which is a ministry of love --- if they know you so incompletely or partially and in such a significant matter.) Whom do you expect to be for others who suffer from chronic illness or various forms of isolation? (I know you said you would let folks know the truth after profession, but consider if this is really the model of dealing with chronic illness you want to set for others in their own lives?) What is your relationship with the God of truth whose power is made perfect in weakness?

Finally, please consider that many diocesan hermits have chronic illnesses while others are aging and becoming more or less disabled in this way. We are finding our way in this as in many things. In my experience dioceses do not usually refuse to profess a person simply because of a chronic illness if that person can live the central elements and spirit of eremitical life at the same time. Some illnesses will not allow this (nor will some vocations), but since a major part of eremitical solitude is its distinction from isolation, most of us find that chronic illness is something eremitical life can redeem in ways which allow illness to be a significant witness to the individual's true value even (and maybe especially) when eremitical life does not occasion healing from the illness itself. If one cannot risk being truthful in this matter it may suggest that one is simply not suited to the risk of eremitical life itself or the radical honesty it demands --- at least not at this point in time. On the other hand, if one's diocese is talking about making a blanket rejection of a chronically ill hermit, perhaps it is time for candidates to educate them, at least generally, re the place of chronically ill hermits in c 603 vocations.

To achieve such education, however, means living the truth in a transparent way, and doing so long and faithfully enough that you can articulate it clearly for your diocese. Eremitical life itself is edifying; the eremitical life of one who is chronically ill or disabled is meant to be doubly so. The basic question your own query raises and which one must answer convincingly will always be, which does one desire more, to live eremitical life and serve the merciful God of truth in this way or to be professed canonically? Canonical profession can and does serve our living out of eremitical life, especially as an ecclesial vocation, but it is a means to the journey of radical truthfulness, authentic selfhood and holiness; it is not the end in itself.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:03 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: chronic illness and disability as vocation, chronic illness and eremitical life, Profession under c 603

23 July 2019

On Writing a Rule as a Formative Process

Good questions. I think that using the exercise of writing several Rules (or rewriting significant parts of Rules, depending on the situation) over a period of several years can work very well for you or anyone whether or not they are seeking to become a diocesan (solitary canonical) hermit. One of the things that is true about writing is it allows us not only to express what we know but also to learn as we write or to bring to conscious awareness insights which were unconscious and largely hidden from us. Struggling to find the right words in a particular context often allows us to make connections with other parts of our writing (and life) we might otherwise not have made. I believe writing a Rule is one of the most important formative experiences a hermit can have. One consolidates what one has learned about living in the silence of solitude and what one has learned about the silence of solitude as a goal of human being. One learns as one writes about who one is with and in terms of God, how God has worked in one's life, how God is present in solitude, what kind of prayer one's relationship with God necessitates, when and how one does this (or allows God to do this!), what work one needs to do, what study, lectio, recreation, rest, and community one must have to be a healthy hermit, and so forth. Until one puts these kinds of things in words, until one articulates how one lives and will protect or foster them, one is not fully aware of them -- or of oneself.

At the same time one will discover where one has no words at all for something which is central to eremitical life. Sometimes we assume we are living all the elements of canon 603 until we attempt to say how and why we live them. Then we may find we have not given sufficient time or thought to a given element. For instance, in my first Rule I completely omitted "stricter separation from the world" because I was really unsure of the validity of the term. I didn't fully understand it and I wasn't sure I could commit to living what I thought it meant! It took me some years to work through the meaning of this term and to formulate what I understood in a way I could commit canonically (publicly) to. Thus, I kept it in mind, read about it, prayed and thought about it, studied the way it might fit in terms of the Gospel and my own vocation and well-being, and generally worked out what I was committing myself to (and what I was NOT committing myself to since there are serious misunderstandings of this term associated with some expressions of monastic life). The difference between silence and solitude and "the silence of solitude" was also something it took me time to understand. Writing allows for consolidation of all of this while planning to eventually write allows one to ponder and pray over what one is being asked to write and commit oneself to. This is helpful not only in formation but discernment as well.

I believe it is imperative to use the elements of canon 603 to guide one's writing and one's life as a hermit even if one is going to be a lay or non-canonical hermit. These elements define the very nature of eremitical life as it is recognized in the Church. Of course if one desires to be professed by the Church and enter the consecrated state of life one clearly has to be living these elements; they are normative for the diocesan hermit. I think, though, that, with the exception of the vows of religious obedience and chastity in celibacy, they are important for the lay hermit living eremitical life in the Catholic Church as well. In all of this they are important points for reflection, study, discussion with others, and for prayer. Your director should be able to assist you in learning about each element and in building them into your life in a way which, more and more, defines that life as eremitical. Journaling or keeping a notebook about them will also be of assistance and help prepare you for writing your own Rule of life and one that is adequate for guiding you for years to come.

My suggestions for writing may differ depending upon whether you are trying to become a diocesan hermit or not (you ask about writing a Rule your diocese will accept but otherwise this is not clear). If you are participating in a mutual discernment process with your diocese you will need to share each version and discuss what growth (formation) each represents when contrasted with the last one and take into account what the Vicar for Religious has to say about the process and your own suitability for eremitical life; beyond this it can be used to help your diocese to gauge your own readiness for vows. Otherwise (if this is a private matter involving private vows or no vows at all) you will need to discuss matters with your SD (spiritual director) and evaluate your growth and possible focuses for the future. Generally I would suggest you begin by writing a summary of what prayer, recreation, study, work, and rest is important in your daily life with God in solitude. Write, for instance, how you maintain the silence of solitude and stricter separation from the world. Write how you serve others, whether in the silence of solitude or in other forms of ministry, what your prayer life looks like, how you understand the penance of eremitical life, religious poverty, etc.

My suggestions for writing may differ depending upon whether you are trying to become a diocesan hermit or not (you ask about writing a Rule your diocese will accept but otherwise this is not clear). If you are participating in a mutual discernment process with your diocese you will need to share each version and discuss what growth (formation) each represents when contrasted with the last one and take into account what the Vicar for Religious has to say about the process and your own suitability for eremitical life; beyond this it can be used to help your diocese to gauge your own readiness for vows. Otherwise (if this is a private matter involving private vows or no vows at all) you will need to discuss matters with your SD (spiritual director) and evaluate your growth and possible focuses for the future. Generally I would suggest you begin by writing a summary of what prayer, recreation, study, work, and rest is important in your daily life with God in solitude. Write, for instance, how you maintain the silence of solitude and stricter separation from the world. Write how you serve others, whether in the silence of solitude or in other forms of ministry, what your prayer life looks like, how you understand the penance of eremitical life, religious poverty, etc.You may not be including all of these elements at present and that's okay. Again, this first document is not so much a Rule as it is a summary of what you are currently living. Start then with this summary; use it as a guide for an eventual Rule and then, with the help of your director, discuss and build in the missing elements over time. At the same time and with an eye on canon 603, be aware of what you are not prepared to write about at all or what does not seem to be working well for you. Discuss these elements (e.g., not enough lectio or study time, silence is problematical somehow, dealing with friends and family, relating with your parish community, supporting yourself from work undertaken within a hermitage, etc) with your director and make adjustments with her assistance. (You can also contact hermits and ask for their input on various topics.) Make notes from time to time on the elements you have not yet included or are unready to write about, read about them, discuss them with any others you might know who do live them (other Religious and even other hermits).

At the end of a year or two during which you will have made changes with the aid of your director, consider whether you are ready to write a Rule which you could commit to live for a year or so. If you are working with a diocese and moving toward public profession this Rule should largely reflect the central elements of canon 603; again, have a discussion with the Vicar for Religious of what you are doing and why; writing in this way can provide your diocese with a significant and substantial means to discern your vocation with you. The Rule you write at this point would be your first draft of an actual Rule, so to speak, and it would be your first attempt to write a plan of eremitical living which meets your own needs and gifts. As you attempt to live it, again attend to what works and what does not, what changing circumstances need to be accommodated in some way, and what dimensions of canon 603 still seem to be beyond your vision of the life; with your director's aid make what changes are necessary. At the end of the year evaluate 1) how well your life and Rule reflect the vision of eremitical life made normative in c 603, and 2) how ready are you to make vows of the evangelical counsels? Usually you will need at least another year or two to learn about and begin to consciously live the evangelical counsels. At the same time you may need to make more changes in your life to accommodate additional elements of c 603.

I believe it is only at the end of this time (so, several years) that you would you even be potentially ready to write a Rule which would be binding in law for profession under canon 603 and it might be wise to write another temporary Rule in the meantime as a means of reflection on and guide to continuing growth. If you are not going to be a candidate for canonical profession, then use the general process of writing a livable Rule every couple of years or so until you have something which really works for you and reflects all the ways you have grown as well as reflecting c 603 as an informal guide to eremitical life as understood by the Church. While I have said "Every couple of years or so" you are, of course, free to use the general process with whatever time units work for you. The basic idea is that writing is helpful in learning and growing to be truly attentive and aware. It also binds you in a conscious way to a way of living and being you desire to do well. If you are not preparing for profession (or if you have already been publicly professed in an institute of consecrated life) you may not need as many "drafts" or temporary Rules. The vows will be familiar to you --- though you will still need to adapt the vow of religious poverty since you will be self-supporting under c 603. Again, writing in this way is meant to provide a means of formation for someone who is self-directed in the way a hermit must be, and the way you indicate desiring to be.

I believe it is only at the end of this time (so, several years) that you would you even be potentially ready to write a Rule which would be binding in law for profession under canon 603 and it might be wise to write another temporary Rule in the meantime as a means of reflection on and guide to continuing growth. If you are not going to be a candidate for canonical profession, then use the general process of writing a livable Rule every couple of years or so until you have something which really works for you and reflects all the ways you have grown as well as reflecting c 603 as an informal guide to eremitical life as understood by the Church. While I have said "Every couple of years or so" you are, of course, free to use the general process with whatever time units work for you. The basic idea is that writing is helpful in learning and growing to be truly attentive and aware. It also binds you in a conscious way to a way of living and being you desire to do well. If you are not preparing for profession (or if you have already been publicly professed in an institute of consecrated life) you may not need as many "drafts" or temporary Rules. The vows will be familiar to you --- though you will still need to adapt the vow of religious poverty since you will be self-supporting under c 603. Again, writing in this way is meant to provide a means of formation for someone who is self-directed in the way a hermit must be, and the way you indicate desiring to be.Please check other posts on this idea of using the writing of a Rule as a formative process. They may be clearer in some ways or add points I have omitted here. Regarding your last two questions, if you write a Rule which is 1) livable, 2) adequate in terms of experience and knowledge of c 603 and solitary eremitical life, and 3) clearly reflects who you are, your commitment to the Gospel, and how you live that out, there is no reason for a diocese to withhold permission for profession or make you write another Rule at this point. However, yes, you need to work at it until your Rule meets these requirements until and unless the diocese indicates they do not believe there is sufficient reason for you to continue in this way. If your diocese ultimately refuses to profess you at some point along the way, the process of formation which writing this Rule has helped shape (and which has helped shape you!!) will still stand you in good stead. I don't think you will fail to realize and appreciate that. In that case you will be able to live your commitment as a lay hermit with or without private vows and with a Rule which can guide your vocation well even if you need to amend or redact it every few years or so. (Occasional amendment or redaction is ordinarily necessary for diocesan hermits as well. I have rewritten my own Rule once since perpetual profession in 2007. I may do so again this year because of significant changes in the way I serve my parish, and the place of increased personal growth work, for instance.)

I wish you well in your project. Feel free to write again if I can be of assistance.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:50 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Formation of a Diocesan or Lay Hermit, Rule and formation, Rule of Life -- writing a rule of life, writing a rule of life, writing to learn

.jpg)