My thanks to a reader for sending this video on to me. She thought it was a great symbol for some of what I have been writing about during the last two weeks and more. I am struck by the degree of trust the finch in this video achieves (apparently finches are shy and skittish) --- and the joy that comes from that trust.

16 August 2015

Entrusting our weakness to the Love of God

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

9:09 PM

![]()

![]()

Canticle of the Turning

Occasionally Sunday liturgies seem especially tailored for me. It is as though God has sneaked into the places of preparation and hearts of the ministers and whispered in peoples' ears, minds, and hearts what songs to choose, what homilies to give, what prayers of intention to offer. Today there were several things that made me feel that way but this song was one of them. My thanks to Sister Michelle Sherliza, OP for her arrangement in this video. Enjoy.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:12 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Canticle of the Turning, Sister Michelle Sherliza OP

When only Weakness and Incapacity are Enough

[[Hi Sister Laurel, you wrote a paragraph about Jesus recently but I am not sure which post it was in. Would you mind reposting it here all by itself? It was about him being stripped of all his individual gifts and talents so God could be the entire source of his honor, and value. I thought it was excellent --- and was intrigued by the idea that Jesus' miracles were not enough!]]

[[Hi Sister Laurel, you wrote a paragraph about Jesus recently but I am not sure which post it was in. Would you mind reposting it here all by itself? It was about him being stripped of all his individual gifts and talents so God could be the entire source of his honor, and value. I thought it was excellent --- and was intrigued by the idea that Jesus' miracles were not enough!]]

Sure, I think I have only written one paragraph on Jesus in the past week or so; here is the one I remember. It fits what you describe. I have broken it in two to make it a bit easier to read. I have written before about Jesus' miracles (in the NT these are really called "works (or acts) of power") not being enough to bring about the reconciliation of all reality so that God might be all in all. cf Madman or Messiah?

What stands out in light of this paragraph and the events of the cross (and the life of Maximillian Kolbe too) is that the greatest thing we can offer the world is our own emptiness made precious and transfigured by the presence of God. When acts of power aren't enough our own emptiness, weakness, and incapacity can be. Another way of thinking of this is that our own stripping and emptiness are themselves the greatest gift we bring, the basis of anything truly miraculous. God can and does work through these more powerfully and exhaustively than he can through anything else. That's one reason Paul says, "My [God's] grace is sufficient for you. My [God's] power is made perfect in weakness." This is, perhaps the Gospel's greatest paradox and the reason at Easter we sing, "O happy fault".

"The Paragraph" (From On Bringing our Entire Availability)

[[When we think of Jesus we see a man whose tremendous potential and

capacity for ministry, teaching, preaching, simple availability and

community, was stripped away. In part this happened through the

circumstances of his birth because he was shamed in this and was seen as

less capable of honorable contributions or faithfulness. In part it was

because he was a carpenter's son, someone who worked with his hands and

was therefore thought of as less intellectually capable. In part it was

because he was more and more isolated from his own People and Religion

and assumed a peripatetic life with no real roots or sources of honor

--- except of course from the One he called Abba.

And in part it was

because even his miracles and preaching were still insufficient to

achieve the transformation of the world, the reconciliation of all

things with God so that God might one day truly be all in all. Gradually

(or not so gradually once his public ministry began) Jesus was stripped

of every individual gift or talent until, nailed to a cross and too

physically weak and incapable of anything else, when he was a failure as

his world variously measured success, [or shamed and dishonored as his culture variously measured dignity and honor] the ONLY thing he could "do" or

be was open to whatever God would do to redeem the situation. THIS

abject emptiness, which was the measure of his entire availability

to God and also to us (!), was the place and way he became truly and

fully transparent to his Abba. It also made the effectiveness of

his ministry and mission global or even cosmic in scope]] as it fully transformed him from Jesus of Nazareth to being the Christ of Faith.

And in part it was

because even his miracles and preaching were still insufficient to

achieve the transformation of the world, the reconciliation of all

things with God so that God might one day truly be all in all. Gradually

(or not so gradually once his public ministry began) Jesus was stripped

of every individual gift or talent until, nailed to a cross and too

physically weak and incapable of anything else, when he was a failure as

his world variously measured success, [or shamed and dishonored as his culture variously measured dignity and honor] the ONLY thing he could "do" or

be was open to whatever God would do to redeem the situation. THIS

abject emptiness, which was the measure of his entire availability

to God and also to us (!), was the place and way he became truly and

fully transparent to his Abba. It also made the effectiveness of

his ministry and mission global or even cosmic in scope]] as it fully transformed him from Jesus of Nazareth to being the Christ of Faith.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

8:57 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: availability, O Happy Fault!, Power perfected in weakness

14 August 2015

Reflection for the Feast (Memorial) of Maximillian Kolbe

N.B., I gave a version of this reflection at a Liturgy of the Word with Communion service today at my parish. The sections in italics were borrowed from the post I wrote earlier for this Feast day and reprised yesterday.

We may think of our humanity as something we possess, a given which cannot be lost, but Christians recognize that our humanity is more a task entrusted to us than it is a possession or simple given. Most specifically humanity is the living reality that comes to be when God who is a constituent part of our very being shines forth within and through us. We are truly human to the extent we image God, not in the weak and inadequate sense of imitating his love and mercy, but in the strong sense of letting these heal and transfigure us. We are truly human to the extent we ARE a covenant with God. Covenant for us is not a mere agreement or arrangement we have undertaken with God as some sort of business partner but something we embody and come more and more to embody over our lifetimes.

We may think of our humanity as something we possess, a given which cannot be lost, but Christians recognize that our humanity is more a task entrusted to us than it is a possession or simple given. Most specifically humanity is the living reality that comes to be when God who is a constituent part of our very being shines forth within and through us. We are truly human to the extent we image God, not in the weak and inadequate sense of imitating his love and mercy, but in the strong sense of letting these heal and transfigure us. We are truly human to the extent we ARE a covenant with God. Covenant for us is not a mere agreement or arrangement we have undertaken with God as some sort of business partner but something we embody and come more and more to embody over our lifetimes.

In Douglas Steere's Together in Solitude, I read the following passage last night. (Steere is a Quaker who writes marvelously on the topics of solitude and community, as well as on silence, prayer and the challenge and task of becoming human.) Here he writes of a story he heard which illustrates part of the task of becoming our truest selves, selves which allow the fire of God's love to flame through us and bring light and warmth to our world. Steere recounts, [[During WWII, a Quaker artist friend of ours who lived in East Berlin painted a water color of three men standing some distance away but in clear view of Christ on the Cross. Each man was holding a mask in his hands and looking up at the crucified one with a mingled gaze of longing and fear: of longing to follow the way to which Christ beckoned him, and of fear both at the loss of his mask which the sight of Christ on the Cross had struck from him and at the price that following the new way might exact of him.]]

Today is the Feast of St Maximillian Kolbe. As I noted in an earlier post his story is as follows: [[Maximillian Kolbe who died on this day in Auschwitz after

two months there, and two weeks in the bunker of death-by-starvation.

Kolbe had offered to take the place of a prisoner selected for starvation in

reprisal when another prisoner was found missing and thought to have escaped.

The Kommandant, taken aback by Kolbe's dignity, and perhaps by the unprecedented

humanity being shown, stepped back and then granted the request. Father

Maximillian sustained his fellow prisoners and assisted them in their dying. He

was one of four remaining prisoners who were murdered in Block 13 (see

illustration below) by an injection of Carbolic Acid when the Nazi's deemed

their death by starvation was taking too long. When the bunker was visited by a

secretary-interpreter immediately after the injections, he found the three other

prisoners lying on the ground, begrimed and showing the ravages of the suffering

they had undergone. Maximillian Kolbe sat against the wall, his face serene and

radiant. Unlike the others he was clean and bright. ]]

Together, these two dimensions of true holiness/authentic humanity result in "a life lived for others," as a gift to them in many ways -- self-sacrifice, generosity, kindness, courage, etc. In particular, in Auschwitz it was Maximillian's profound and abiding humanity which allowed others to remember, reclaim, and live out their own humanity in the face of the Nazi's dehumanizing machine. No greater gift could have been imagined in such a hell.]] This was a man with no masks at all, no obstacles to the God who lived within and was mediated by him to others. He was authentically human only to the extent he revealed the God who is Love-in-act to others

In today's readings the accent is on our God, his mercy and what he does with human weakness and the stripping that life brings our way. In Joshua, for instance, the lection is a litany of verbs contrasting human need and the dynamic of Divine mercy: You were captive, lost, hungry, threatened, homeless and childless, and I delivered, fed, gave to, assigned, brought you, led you, planted for you, etc. In every instance God is revealed as the merciful one who gifts us in our weakness and incapacity. The real fruitfulness of our lives is God's work in and through us. The passage comes to a climax in the following reminder: [[I gave you a land that you had not tilled and cities that you had not built, to dwell in; you have eaten of vineyards and olive groves which you did not plant.]] As difficult as some of the examples might be for us Israel struggled to affirm the truth that genuinely fruitful lives are reflections of the unmerited mercy and love of God.

In the gospel lection Matthew speaks of two of the main ways human beings are made increasingly ready and able to image and mediate God's love to others. The first is marriage where to some degree husbands and wives set aside their own agendas and honestly embrace their own strengths and weaknesses for the sake of spouse, of children, of their children's children, the church, the world around us and, of course, for God's own sake (for the sake of Love itself) as well. It is a life demanding profound honesty and sacrifice if it is to be the sacramental reflection of the union between God and the Human Person it is meant to be.

In the gospel lection Matthew speaks of two of the main ways human beings are made increasingly ready and able to image and mediate God's love to others. The first is marriage where to some degree husbands and wives set aside their own agendas and honestly embrace their own strengths and weaknesses for the sake of spouse, of children, of their children's children, the church, the world around us and, of course, for God's own sake (for the sake of Love itself) as well. It is a life demanding profound honesty and sacrifice if it is to be the sacramental reflection of the union between God and the Human Person it is meant to be.The second is religious life where Sisters and Brothers commit to stripping the masks we might adopt and wear otherwise and eschewing the things which might mark us as valuable in ordinary terms: the mask of financial success and wealth, the mask of power and influence, and finally, even the mask of our own will and agenda --- our own identity as director of the course of our own inner and outer worlds, however great or small we perceive these to be. Through this renunciation and a life of prayer we also open ourselves to allowing God to be the sole source of strength and validation in our lives. In this life too we embrace both joy and sacrifice for the sake of Love itself.

In my own vocation, what is true is that the hermit commits to laying aside many of her gifts simply so that she may witness to God's love and who that makes her to be; she commits to being a revelation of the covenant each person is with God, to the completion that we each know in God even when stripped of all of the talents we associate with ourselves and apostolic ministry. And that is really true of each of us as well. Our humanity is our most fundamental vocation and the greatest task of our lives. Whatever the vocational path we take to that union with God we are each called to be, it is humanity itself that is "our" (God's) greatest achievement and the single most important gift we can bring to the inhuman situations still so prevalent in our world. That is one of the lessons of Maximillian Kolbe's life and the real nature of any call to holiness.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

3:17 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A Vocation to Love, humanity -- a task we accept, Humanity as Covenant reality, Maximillian Kolbe, Naming the Communion that is the Human Heart

12 August 2015

Treat them as you would Gentiles and Tax collectors (reprise)

In today's Gospel pericope we hear Jesus telling folks to speak to those who have offended against God one on one and then, if that is ineffective, bring in two more brothers or sisters to talk with the person, and then, if that too is ineffective, to bring matters to the whole community --- again so the offended can be brought back into what we might call "full communion". If even that is ineffective then we are told to treat the person(s) as we treat Gentiles and tax collectors. In every homily I have ever heard about this passage this final dramatic command has been treated as justification for excommunication. Even today our homilist referred to excommunication --- though, significantly, he stressed the medicinal and loving motive for such a dire step. The entire passage is read as a logical, common-sense escalation and intervention: start one on one, try all you can, bring others in as needed, and if that doesn't work (that is, if the person remains recalcitrant) then wash your hands of him or, if stressing the medicinal nature of the act, separate yourselves from him until he comes to his senses and repents! In this reading of the text Matthew is giving us the Scriptural warrant for "tough love."

In today's Gospel pericope we hear Jesus telling folks to speak to those who have offended against God one on one and then, if that is ineffective, bring in two more brothers or sisters to talk with the person, and then, if that too is ineffective, to bring matters to the whole community --- again so the offended can be brought back into what we might call "full communion". If even that is ineffective then we are told to treat the person(s) as we treat Gentiles and tax collectors. In every homily I have ever heard about this passage this final dramatic command has been treated as justification for excommunication. Even today our homilist referred to excommunication --- though, significantly, he stressed the medicinal and loving motive for such a dire step. The entire passage is read as a logical, common-sense escalation and intervention: start one on one, try all you can, bring others in as needed, and if that doesn't work (that is, if the person remains recalcitrant) then wash your hands of him or, if stressing the medicinal nature of the act, separate yourselves from him until he comes to his senses and repents! In this reading of the text Matthew is giving us the Scriptural warrant for "tough love."

But I was struck by a very different reading during my hearing of the Gospel this morning. We think of Jesus turning things on their heads so very often in what he says; more we think about how often he turns things on their head by what he does. With this in mind the question which first occurred to me was, "But what would this have meant in Jesus' day for disciples of this man from Nazareth --- not what would it have meant for hundreds of years of Catholic Christianity!? Is the logic of this reading different, even antithetical to the logical, commonsense escalation outlined above?" And the answer I "heard" was, "Of course it is different! I am asking you to escalate your attempts to bring this person home, not to wash your hands of her. To do that I am suggesting you treat her as you might someone for whom the Gospel is a foreign word now -- someone who needs to hear it as much or more than you ever did yourself." Later I thought in a kind of jumble, "That means to treat her with even greater gentleness and care, even greater love and a different kind of intimacy. Her offense has effectively put her outside the faith community. Jesus is asking that we let ourselves be the "outsider" who stands with her where she is. He is saying we must try to speak in a language she will truly hear. Make of her a neighbor again; meet her in the far place, learn her truth before we try to teach her "ours". After all, what I and others have said thus far has either not been understood or it was not compelling for her."

While I should not have been surprised, I admit I was startled by my initial thoughts! Of course I knew that Jesus associated with tax collectors and with Gentiles. The reading with the Canaanite women last week or the week before makes it clear that Jesus even changed his mind about his own mission in light of the faith he found among Gentiles. Meanwhile, today's reading is taken from a Gospel attributed to Matthew, an Apostle who is identified as a tax collector! Shouldn't we be holding onto our seats in some anticipation while listening for Jesus – as he always does -- to say something that turns conventional wisdom and our entire ecclesiastical and spiritual world on its head? Maybe my thoughts were not really so crazy after all and maybe those homilies I have heard for years have NOT had it right! So I looked again at the Gospel lection from today in its Matthean context. It is sandwiched between passages about humbling ourselves as children (those with no status), not being a source of stumbling and estrangement to others, searching for the one sheep that has gone astray even if it means leaving behind the 99 who have not strayed, and Peter asking how often he should forgive his brother to which Jesus says seven times seventy!

While I should not have been surprised, I admit I was startled by my initial thoughts! Of course I knew that Jesus associated with tax collectors and with Gentiles. The reading with the Canaanite women last week or the week before makes it clear that Jesus even changed his mind about his own mission in light of the faith he found among Gentiles. Meanwhile, today's reading is taken from a Gospel attributed to Matthew, an Apostle who is identified as a tax collector! Shouldn't we be holding onto our seats in some anticipation while listening for Jesus – as he always does -- to say something that turns conventional wisdom and our entire ecclesiastical and spiritual world on its head? Maybe my thoughts were not really so crazy after all and maybe those homilies I have heard for years have NOT had it right! So I looked again at the Gospel lection from today in its Matthean context. It is sandwiched between passages about humbling ourselves as children (those with no status), not being a source of stumbling and estrangement to others, searching for the one sheep that has gone astray even if it means leaving behind the 99 who have not strayed, and Peter asking how often he should forgive his brother to which Jesus says seven times seventy!

I think Jesus is reminding us of the difference between a community which is united in and motivated by Christ's own love (a very messy business sometimes) and one which is united in and mainly concerned with discipline (not so messy, but not so fruitful or inspired either). I think too he is reminding us of a Church which is always a missionary Church, always going out to others, always seeking to reconcile the entire world in the power of the Gospel. It is not a fortress which protects its precious patrimony by shutting itself off from those who do not believe, letting them fend for themselves or simply find their own ways to the baptistry or confessional doors; instead it achieves its mission by extending its love, its Word, and even its Sacraments to those who most need them --- the alien and alienated. It is a Church that really believes we hold things as sacred best when we give them away (which is NOT the same thing as giving them up!). Meanwhile Jesus may also be saying, "If your brother or sister has not and will not hear you, perhaps you have not loved them well or effectively enough; find a new way, even a more costly way. After all, my way (the Way I am!) is not the way of conventional wisdom, it is the scandalous, foolish, and sacrificial way of the Kingdom of God!

I had always thought today's reading a "hard one" because it seemed to sanction the excommunication of brothers and sisters in Christ. But now I think it is a hard one for an entirely different reason. It gives us a Church where no one can truly be at home so long as we are not reaching out to those who have not heard the Gospel we have been entrusted with proclaiming. It is a Church of open doors and open table fellowship (open commensality) because it is a church of open and missionary hearts -- just as God's own heart, God's own essential nature, is missionary. Above all it is a church where those who truly belong are the ones who really do not belong anywhere else! We proclaim a Gospel in which we who belong to Christ through baptism are the last and those outside our communion are first and, at least potentially, the Apostles on which the Church is built.

When we treat people like Gentiles and tax collectors we treat them in exactly this way, namely, as those whose truest home is around the table with us, listening to and celebrating the Word with us, ministering to and with us as at least potential brothers and sisters in Christ! We treat them as Gentiles and tax collectors when we take the time to enter their world so that we can speak to them in a way they can truly hear, when we love them (are brothers and sisters to them) as they truly need, not only as we are comfortable doing in our own cultures and families. Paul, after all, spoke of becoming and being all things to all persons --- just as God became man for us. He was not speaking of indifferentism or saying with our lives that Christ doesn't really matter; just the opposite in fact. He was telling us we must be Christians in this truly startling way --- persons who can and do proclaim the Gospel of a crucified and risen Christ wherever we go because we let ourselves be at home and among (potential) brothers and sisters wherever we go. We do as God did for us in Christ; we let go of the prerogatives which are ours and travel to the far place in any and all the ways we need to in order to fulfill the mission of our God to truly be all in all.

When the logic, drama, and tension of today's Gospel lection escalate it is to this conclusion, I think, not to a facile justification of excommunication. In this pericope Jesus does not ask us to progressively enlist more people to increase the force with which we strong arm those who have become alienated, much less to support us as we cut them loose if they are unconvinced and unconverted, but to offer them richer, more diverse and extensive chances to be heard and to hear --- increasing opportunities, that is, to be empowered to change their minds and hearts when we, acting alone, have failed them in this way. This is what it means to forgive; it is what it means to be commissioned as an Apostle of Christ. And if that sounds naive, imprudent, impractical, and even impossible, I suspect Jesus' original hearers felt the same about the pericopes which form this lection's immediate context: becoming as children with no status except that given them by God, leaving the 99 to seek the single lost sheep or forgiving what is effectively a countless number of times. Certainly that's how someone writing under the name of a tax collector-turned-Apostle presents the matter.

When the logic, drama, and tension of today's Gospel lection escalate it is to this conclusion, I think, not to a facile justification of excommunication. In this pericope Jesus does not ask us to progressively enlist more people to increase the force with which we strong arm those who have become alienated, much less to support us as we cut them loose if they are unconvinced and unconverted, but to offer them richer, more diverse and extensive chances to be heard and to hear --- increasing opportunities, that is, to be empowered to change their minds and hearts when we, acting alone, have failed them in this way. This is what it means to forgive; it is what it means to be commissioned as an Apostle of Christ. And if that sounds naive, imprudent, impractical, and even impossible, I suspect Jesus' original hearers felt the same about the pericopes which form this lection's immediate context: becoming as children with no status except that given them by God, leaving the 99 to seek the single lost sheep or forgiving what is effectively a countless number of times. Certainly that's how someone writing under the name of a tax collector-turned-Apostle presents the matter.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:17 AM

![]()

![]()

09 August 2015

On the Question of Selfishness versus Hiddenness lived for Others

[[ Sister Laurel, are you saying it is unnecessary to use our gifts? Aren't hermits called to use their gifts? Also, how can one tell the difference between selfishness and the generous hiddenness of the hermit?]]

[[ Sister Laurel, are you saying it is unnecessary to use our gifts? Aren't hermits called to use their gifts? Also, how can one tell the difference between selfishness and the generous hiddenness of the hermit?]]

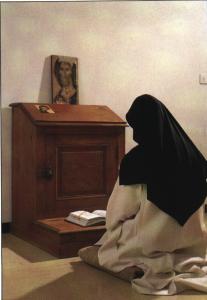

Thanks for your questions. I have been straining to speak of what is primary or most foundational in the hermit's life, what, above all, they witness to for the sake of others. To do this I have had to point to one dimension of the life --- although I think it is most basic, namely, that the hermit in her poverty and emptiness is called to live the relationship with God which is actually at the heart of every genuine act of ministry. Below all the gifts we are given to develop and use stands this relationship; it is, in fact, the very essence of what it means to be human. We ARE this relationship, this covenant with God, or we are simply not human. The hermit commits herself to a life of prayer, to the realization or perfection of this relationship. When we speak of human wholeness or holiness we are speaking of this fundamental covenantal relationship and its fullness and sufficiency in this person's life.

Of course we are called to use our gifts. I believe we will do that effectively to the extent this relationship with God is really the heart of our lives. Otherwise our "ministry" will be an expression of self-assertion instead of the mission of God. But there are few vocations in the Church which point to this truth in quite the same way as that of contemplatives and especially hermits and recluses. Our lives speak to the primacy of our relationship with God. They especially do that if we are made more fully human in the silence of solitude, if, in fact, we come to greater wholeness, greater capacity to love not only God but ourselves and others.

To sit in prayer is a gift of self to God and it is really something we do for the sake of others (first God, then all human beings). It means giving one's time, energy, attention, hopes, dreams, questions and desires to God so that God might have our lives as a dedicated place of personal presence. To sit in prayer extends the Kingdom of God in our world in ways which transcend our own small lives. It can mean foregoing more obvious gifts of self to others in order 1) to worship the God who deserves our entire attention, and 2) to at least raise the God/Meaning question in others' minds in a way which affirms we truly believe the inescapable love of God is the foundation of and impulse behind everything --- including every gift, ministry, and service we do for others. If we live our lives well then they may effectively invite others to entrust themselves to God similarly --- whatever the individual vocation.

To sit in prayer is a gift of self to God and it is really something we do for the sake of others (first God, then all human beings). It means giving one's time, energy, attention, hopes, dreams, questions and desires to God so that God might have our lives as a dedicated place of personal presence. To sit in prayer extends the Kingdom of God in our world in ways which transcend our own small lives. It can mean foregoing more obvious gifts of self to others in order 1) to worship the God who deserves our entire attention, and 2) to at least raise the God/Meaning question in others' minds in a way which affirms we truly believe the inescapable love of God is the foundation of and impulse behind everything --- including every gift, ministry, and service we do for others. If we live our lives well then they may effectively invite others to entrust themselves to God similarly --- whatever the individual vocation.

On the Distinction Between Selfishness and Generous Hiddenness:

How do we tell the difference between selfishness and a hiddenness which is lived for others? One fundamental way is by the hermit's living of the Rule she has written and the Church has approved canonically. It is important to understand that a Rule is approved with the sincere expectation and hope that it will lead to the generous living of an authentically eremitical life under canon 603. Canonists look at proposed Rules with an eye to their canonical soundness but bishops look at a hermit's Rule for the sense that it is a sound expression of gospel life lived in the silence of solitude. It is a document that reflects a sense of the life defined in the canon as well as the individual hermit's own unique way of embodying that. Moreover, when a Rule is approved the hope it will serve in the anticipated way is often explicitly mentioned in the Bishop's formal document of approval. One of the reasons Rules are rewritten occasionally is to be sure they really serve the hermit in her authentic living of an eremitical life which truly honors the vocation (including the public rights and obligations) the Church has extended to this person.

A second sign of a hiddenness which is lived for others is that the silence of solitude really leads to a more generous, more loving person who is more fully alive and more truly a mediator of the presence of God than was the case in a different context. I think it is easy to find so-called hermits whose lives and language have a coating of piety but who, in general, are unhappy, misanthropic, unfulfilled, and selfish. It is not enough to persevere in fidelity to one's Rule if there is no joy, no more abundant life, no signs of genuine growth and increasing personal and spiritual maturity. Faithfulness to one's Rule is important, even foundational, but it must produce characteristic fruit in the hermit's life or it is much more likely we are dealing with a distorted and crippled individualism disguised as faithfulness and perseverance.

A second sign of a hiddenness which is lived for others is that the silence of solitude really leads to a more generous, more loving person who is more fully alive and more truly a mediator of the presence of God than was the case in a different context. I think it is easy to find so-called hermits whose lives and language have a coating of piety but who, in general, are unhappy, misanthropic, unfulfilled, and selfish. It is not enough to persevere in fidelity to one's Rule if there is no joy, no more abundant life, no signs of genuine growth and increasing personal and spiritual maturity. Faithfulness to one's Rule is important, even foundational, but it must produce characteristic fruit in the hermit's life or it is much more likely we are dealing with a distorted and crippled individualism disguised as faithfulness and perseverance.A third sign that we are not dealing with selfishness is the well-grounded conviction that this person is living this life so that they may witness to the God who meets our emptiness with his fullness.The life leading to this conviction has a number of faces, some more distinct than others, some less developed or explicit. In general though it has two aspects which are central to the hermit's lived commitment: 1) the sense that God can only be God in our world if we are obedient (open and responsive) to God's call; 2) the sense that we can only give what God empowers us to give which requires both prayer and penance (together these lead to an, emptying in preparation for, an opening to, and also a filling with the dynamic power of God). This lived commitment may include an experience of profound emptiness and stripping by the circumstances of life which God makes sense and use of --- not because God wills or "causes these circumstances", but because God transfigures them with his presence. This is certainly the message of the Cross with Jesus' descent into hell and subsequent bodily resurrection.

For the person of faith, suffering leads to obedience not because it breaks us down and makes us do the will of God rather than our own, but because it opens us to the profoundest weakness, incapacity, and emptiness and therefore, to the most fundamental and neuralgic questions of meaning. Suffering opens us to the "answer" we know as God. When we are empty and incomplete we can be open to being filled and completed by the One who bears witness to Himself within us. We cannot actually be open to being completed by God if we already know ourselves as complete, nor to the answer God is if we refuse to pose the question of our own existence in as radical a way as is possible. I see hermits, therefore, as people who pose the question(s) of God and meaning as radically as possible.

This also leads us to a sense that our very emptiness and the things which cause them open us to the greatest gift others need as well. We must come to know our own pain and need as a miniscule fraction of the pain and need of a suffering world and thus we know that our own consolation and redemption point to something the world needs. Our lives, redeemed and transfigured, empty perhaps of usable gifts, strength, worldly wisdom or expertise, and the opportunities to use these as apostolic religious do, reveal the God who freely completes and empowers us nonetheless --- if we will only entrust our lives to him.

This also leads us to a sense that our very emptiness and the things which cause them open us to the greatest gift others need as well. We must come to know our own pain and need as a miniscule fraction of the pain and need of a suffering world and thus we know that our own consolation and redemption point to something the world needs. Our lives, redeemed and transfigured, empty perhaps of usable gifts, strength, worldly wisdom or expertise, and the opportunities to use these as apostolic religious do, reveal the God who freely completes and empowers us nonetheless --- if we will only entrust our lives to him.The focus here, however, is God. If the hermit or hermit candidate focuses instead on her own suffering, her own pain and yearning for meaning, or if she begins instead to distract herself from these and thus from the God who reveals Godself in such circumstances, she has shifted from the authentic dynamic of the eremitical life and substituted an ungenerous self centeredness in its place. I should note that this is the primary reason essential healing and personal work needs to be done before one retires to solitude. It is also a central reason this vocation is recognized as a second-half-of-life vocation. One needs to have experienced the kinds of stripping and maturing that ordinarily occur in adulthood --- and especially in the demands of life with others --- to become open to God in the radical way eremitical life represents. One then needs to learn over time in solitude to truly turn to God, truly open to God in ways which allow his ever fuller indwelling and one's own transfiguration.

The fact is that there are some hermits whose lives do not immediately reflect one or the other of these aspects of the dynamic outlined. Some have not been stripped by the circumstances of life; generally, these hermits will open to God more slowly as the rigor of the life with its tedium and routine do as they are meant. But there are others who have been stripped of many things by the exigencies of life but, for instance, whose spirituality does not allow them to really open to the transfiguring presence of God. They may, for instance, resent and grieve the various forms of stripping and emptying life has required or occasioned but never commit to or undertake the work associated with healing these. When this is true such persons find it difficult indeed to open (or let God open them) to the even greater stripping and self-emptying involved in giving their whole selves over to God. In such situations the "hermitage" is a refuge from change and "the world out there" while in truth the hermit carries "the world" she is meant to separate herself from so deeply in her heart that genuine transfiguration becomes nearly impossible. Because of its pious veneer and the self-delusion at its core such a life can actually become an instance of the sin against the Holy Spirit rather than an authentic eremitical LIFE which is more and more wholly given over to that Spirit --- and thus lived for others.

The fact is that there are some hermits whose lives do not immediately reflect one or the other of these aspects of the dynamic outlined. Some have not been stripped by the circumstances of life; generally, these hermits will open to God more slowly as the rigor of the life with its tedium and routine do as they are meant. But there are others who have been stripped of many things by the exigencies of life but, for instance, whose spirituality does not allow them to really open to the transfiguring presence of God. They may, for instance, resent and grieve the various forms of stripping and emptying life has required or occasioned but never commit to or undertake the work associated with healing these. When this is true such persons find it difficult indeed to open (or let God open them) to the even greater stripping and self-emptying involved in giving their whole selves over to God. In such situations the "hermitage" is a refuge from change and "the world out there" while in truth the hermit carries "the world" she is meant to separate herself from so deeply in her heart that genuine transfiguration becomes nearly impossible. Because of its pious veneer and the self-delusion at its core such a life can actually become an instance of the sin against the Holy Spirit rather than an authentic eremitical LIFE which is more and more wholly given over to that Spirit --- and thus lived for others.A Postscript on the place of canonical standing in regard to your question:

To reiterate, the Church is responsible for publicly professing hermits who live lives of generous hiddenness, not lives of selfish indulgence and individualism. This is because truly generous eremitical lives serve God and others precisely in their profound emptinesses and stripping --- when God is allowed to meet these with his fullness. There is, for the hermit, no middle ground here I think. Either one commits to live for God and those precious to God by one's openness to being redeemed and transfigured or one fails to do so. For instance, there is little or no apostolic ministry to attenuate the starkness of the choice here. Nor does one retire from being a hermit whose entire life poses (and is given over to posing) this fundamental choice as radically as possible. Canonical standing not only attests to the authenticity of the vocation but the graced state (the consecrated state of life), the relationships (legitimate superiors, diocesan stability, etc), and the public accountability such standing both indicates and helps insure but it supports one in living this out exhaustively with and for the whole of one's life. Again, canonical standing in this matter serves love on a number of levels.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:13 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: canonical standing --- relational standing, Eremitical Hiddenness, Reasons for seeking canonical standing, self-centeredness, Sin against the Holy Spirit

08 August 2015

On the Problem with Long-Winded Prayers

[[Dear Sister, why would Jesus prohibit long prayers with many words? And if God knows what we need before we pray, why do we pray at all? Do you have a favorite prayer you use every day?]]

[[Dear Sister, why would Jesus prohibit long prayers with many words? And if God knows what we need before we pray, why do we pray at all? Do you have a favorite prayer you use every day?]]

I think you are referring to Matthew's instruction on prayer, no? The answer, I think has several aspects. The first is a matter of history and especially of the concern with idolatry. You see when Matthew's gospel was written belief in the power of prayer was tenuous. Folks did believe if they called on God by name God would be forced to answer but this was a far cry from turning oneself over to God in trusting submission. As a result however, people developed lists of all of the names of gods (or God) known. These "magic papyri" were then taken and someone would stand on the equivalent of the street corner and read off all the names believing that a prayer would be answered of the correct name was used; to know and call upon one's name indicated power over that person. This long-winded usage is more that of incantation than it is one of genuine invocation because one was not really calling upon God by name in trust and intimacy! In any case, the first reason for Matthew-Jesus' instructions was a way of weaning folks from this magical or superstitious and idolatrous approach to prayer and the use of God's name. (And of course this was buttressed by the invocation of the prayer which allowed us to call upon God as Abba --- the name of God Jesus used in a unique sense.)

The second reason has to do with distraction and focus. When we go on and on in our prayers, when, that is, we talk and talk it is a good deal harder to stay in touch with our deepest feelings and sense of neediness. (Partly this is because these may well be beyond words. Partly it is because naming specific aspects of this neediness can cause other aspects to be excluded from consciousness and our prayer.) Moreover, we may simply become enamored of hearing our own prayer and in a related vein, we may be more focused on our own piety, etc., than we actually are on God. If you pay attention to yourself and your own inner situation in prayer sometime, note how reading a long rote prayer or waxing on with your own prayer becomes less about God and more about yourself, your concerns with whether you have said it all, said it well enough, impressed God with your need or your devotion or your eloquence, etc. Note also how diffused or weakened your sense of profound need has become, how other things take the place of the one overarching concern that caused you to turn to God in the first place.

I used the picture of the Prodigal Son and Father above here because one thing that is really striking to me in light of this conversation is how the Father cuts off the son's long and rehearsed speech of "repentance". It is not that the Father does not listen, but that he really accepts the son more fully and profoundly than the son's proposal would have allowed for. You see when I read the proposed speech I hear the Son distancing himself further and further from the deep and complete sense of sorrow, contrition, and unworthiness he feels (or felt initially!).

I used the picture of the Prodigal Son and Father above here because one thing that is really striking to me in light of this conversation is how the Father cuts off the son's long and rehearsed speech of "repentance". It is not that the Father does not listen, but that he really accepts the son more fully and profoundly than the son's proposal would have allowed for. You see when I read the proposed speech I hear the Son distancing himself further and further from the deep and complete sense of sorrow, contrition, and unworthiness he feels (or felt initially!).

He begins to propose solutions in that speech, mitigations, equivocations, compromises, and a final surrendering of his actual identity and dignity. He says he can be a servant rather than a son and heir, and though there is a statement of unworthiness included, the chances that he might be raised to the dignity of true humility rather than admitted to a kind of softened and tolerable humiliation is taken out of his Father's hands. But in prayer the point is to put our whole selves into our Father's hands and allow him to dispose of us as he will. After all, God knows what we truly need! The purpose of prayer is to allow God to do what only God can do, to raise us to a genuine humility --- to the truth of who we are in light of God's love --- not to propose a tolerable but punishing shamefulness in its place. Again and again this is the message of Jesus' encounter with sinners and the larger culture. I guess that generally I see long-winded prayers as following the pattern of the prodigal son's speech; more often than not they involve our own attempt to control things, our own tendency to substitute human wisdom and justice for divine, and thus, our failure to radically trust the depth of God's love or the scope and wisdom of his mercy. By the way, it may well be that one of the real mercies of God, one of the ways God demonstrates knowing what we really need long before we do --- much less long before we put this into words --- is precisely in cutting off our long-winded, often well-rehearsed prayers!

In any case, generally speaking, if one can go on and on in a relatively eloquent prayer, one has distracted oneself from the starkness of one's concerns and need for God. One has ceased to be a poor person seeking only what God desires to give. One has also distracted oneself from the difficult work of waiting on God and discerning the way God is working. The really classic example of a prayer that "says it all" and allows for our entire submission of self to God's creative and redemptive love without distraction or attenuation is the Jesus Prayer, "O God (Lord Jesus Christ), have mercy on me a sinner!" God is praised in the very giving of ourselves and in our allowing him to gift us as he will. To my mind there is no greater praise of God than this. Meanwhile, to answer your second question, we pray in order to pose the question we are so that God might be the answer he is, the answer we need, the answer we cannot supply or be on our own. We are not giving God information when we pray; we are giving God ourselves in an attitude or posture of openness and vulnerability. God has already given himself to us. Our prayer lets that gift be accepted and received.

In any case, generally speaking, if one can go on and on in a relatively eloquent prayer, one has distracted oneself from the starkness of one's concerns and need for God. One has ceased to be a poor person seeking only what God desires to give. One has also distracted oneself from the difficult work of waiting on God and discerning the way God is working. The really classic example of a prayer that "says it all" and allows for our entire submission of self to God's creative and redemptive love without distraction or attenuation is the Jesus Prayer, "O God (Lord Jesus Christ), have mercy on me a sinner!" God is praised in the very giving of ourselves and in our allowing him to gift us as he will. To my mind there is no greater praise of God than this. Meanwhile, to answer your second question, we pray in order to pose the question we are so that God might be the answer he is, the answer we need, the answer we cannot supply or be on our own. We are not giving God information when we pray; we are giving God ourselves in an attitude or posture of openness and vulnerability. God has already given himself to us. Our prayer lets that gift be accepted and received.

Personally my own favorite brief prayer, and the one I use all the time is "O God come to my assistance, O Lord make haste to help me!" It stresses the urgency of my prayer, and it helps me be patient. It also reflects my own certainty that God knows what I need and will assist as is best; thus, for me it combines need with faith. Nor does it distance me from the deep feelings involved here. For both praise and plea I tend to go back to my Franciscan roots, My God and my all! This also articulates my greatest needs and aspirations, the goal and ground of any eremitical life. When, we stay in touch with the deep feelings associated with our prayer, we are ready to receive the answer to our prayer whenever and how ever that comes to us. It is essential to "hearing" the answer God's presence will be for us. We can only receive God to the extent we pose the question we are. If we have distracted ourselves from the depths and keenness of our feelings, we have made it impossible for God to be the answer we need to the extent we need him to be that.

Besides the prayer, "O Lord make haste . . ." my favorite prayer is the "Lord's Prayer". While I say it at Mass, Communion services, and during Office, I don't usually recite it otherwise. Instead I tend to break it up into individual focuses, petitions, or thought units, and meditate on those --- usually for a number of days or weeks. My favorite prayer at night is the "nunc dimittis" but for a short prayer I like and use, "Protect us as we stay awake, watch over us as we sleep" either with or without the continuing "that awake we may keep watch with Christ and asleep rest in his peace." Both of these are from the office of Night Prayer. The latter is something I find especially helpful when I am unwell.

Besides the prayer, "O Lord make haste . . ." my favorite prayer is the "Lord's Prayer". While I say it at Mass, Communion services, and during Office, I don't usually recite it otherwise. Instead I tend to break it up into individual focuses, petitions, or thought units, and meditate on those --- usually for a number of days or weeks. My favorite prayer at night is the "nunc dimittis" but for a short prayer I like and use, "Protect us as we stay awake, watch over us as we sleep" either with or without the continuing "that awake we may keep watch with Christ and asleep rest in his peace." Both of these are from the office of Night Prayer. The latter is something I find especially helpful when I am unwell.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:04 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: humbling vs humiliation, Lord's Prayer, Parable of the Merciful Father, parable of the prodigal son, Prayer, prayer_long-winded, raised to humility

04 August 2015

Followup Questions on the notion of Bringing "One's Entire Availability"

[[Sister Laurel, Can it be that simple - that God just wants me to live "on friendly terms" with him? (It brings tears to my eyes to just write this sentence.) Is that what the "abyss" is all about? Just to live with him even when I don't feel him present and only know by faith he has promised to be there - "on friendly terms?" To do all the mundane things "with him" - not even "for him" - because I can't bring anything worth having except my being entirely available to him? So where, then, does the "doing" fit in -- the seeking/seeing him in others, serving him by serving others? Since I am not a hermit, how does this translate to the active life - because I think it must. How do I "spend myself" if I bring nothing worth having to him? ]]

[[Sister Laurel, Can it be that simple - that God just wants me to live "on friendly terms" with him? (It brings tears to my eyes to just write this sentence.) Is that what the "abyss" is all about? Just to live with him even when I don't feel him present and only know by faith he has promised to be there - "on friendly terms?" To do all the mundane things "with him" - not even "for him" - because I can't bring anything worth having except my being entirely available to him? So where, then, does the "doing" fit in -- the seeking/seeing him in others, serving him by serving others? Since I am not a hermit, how does this translate to the active life - because I think it must. How do I "spend myself" if I bring nothing worth having to him? ]]

Thanks for your questions and the chance to reflect on all this further. My own thought is coming together in new ways in all of this so I offer this response with that in mind. Here is a place where words are really critical. First, yes, it is that simple but no one ever said simple meant easy or without substantial cost. Neither does simple mean that we get there all at once. This is simple like God is simple, like union with God is simple, like faith is simple. In other words it speaks as much of a goal we will spend our whole lives attaining as it does the simplicity of our immediate actions. That quotation (from The Hermitage Within regarding bringing one's entire availability and living on friendly terms with God) is something I read first in 1984 some months after first reading canon 603. I posted it in the sidebar of this blog in 2007 as I prepared for solemn profession. And now I have returned to it yet again only from a new place, a deeper perspective. It represents one of those spiral experiences, the kind of thing T.S. Eliot writes about when he says: [[We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.]]

Secondly, the quotation referred to bringing " my entire availability" not just to "being entirely available". While these two realities are profoundly related and overlap, I hear the first as including the second but therefore as committing to something more as well. I think bringing one's entire availability means bringing one's whole self for God's own sake so that God might really be God in all the ways that is so. As you say, it implies being available to God, doing things with God, being open to awareness of God and God's will, but more, it says "I bring you all my gifts, all my neediness and deficits, myself and all the things that allow you to be God. I open myself to your love, your recreation, your healing, your sovereignty, your judgment; I bring myself in all the ways which might allow you to be God in my life and world." It means, I think, that I allow myself to be one whose entire purpose and meaning is in the mediation of God's presence and purposes. And this, I think, is a commitment to being entirely emptied and remade so that my whole life becomes transparent to God.

Secondly, the quotation referred to bringing " my entire availability" not just to "being entirely available". While these two realities are profoundly related and overlap, I hear the first as including the second but therefore as committing to something more as well. I think bringing one's entire availability means bringing one's whole self for God's own sake so that God might really be God in all the ways that is so. As you say, it implies being available to God, doing things with God, being open to awareness of God and God's will, but more, it says "I bring you all my gifts, all my neediness and deficits, myself and all the things that allow you to be God. I open myself to your love, your recreation, your healing, your sovereignty, your judgment; I bring myself in all the ways which might allow you to be God in my life and world." It means, I think, that I allow myself to be one whose entire purpose and meaning is in the mediation of God's presence and purposes. And this, I think, is a commitment to being entirely emptied and remade so that my whole life becomes transparent to God.

As I think more about this it seems to me "my entire availability" is something we can only offer God. "My entire availability" seems to me to mean bringing myself to God in ways which would possibly be an imposition, unsafe (for them and for me), and pastorally unwise or simply unloving in the case of others. "Being entirely available," on the other hand, sounds to me like bringing myself as I am and allowing God to share in my activities and life as it is but, for instance, not necessarily giving God my entire future and past, my entire self -- body and soul, physically, mentally and spiritually. It also sounds like the focus is on gifts, but not on emptiness and need. Our world is certainly familiar with the idea of bringing one's gifts, but to bring one's "weakness," "shame", and inabilities is rarely recognized as something we are called to sign up for at church (or wherever) to offer to others. Despite the importance of vulnerability in pastoral ministry bringing one's "weakness," "shame", deficits, and inabilities is rarely recognized as something we must offer to God if we are to bring others the Gospel as something whose truth we know intimately.

Thus, I think, that "entire availability" means that I also bring my deficits and deficiencies and that I do so trusting that God can make even these bits of emptiness something infinitely valuable and even fruitful to others. To be available to God and to bring one's entire availability may indeed be the same thing but they sound different to me --- overlapping, yes, but different. Whether I am correct or not in this, the formulation in the passage quoted from The Hermitage Within pushes me to envision something much more total and dynamic than the other formulation. Other things push me to this as well, not least Paul and Mark's theologies of the cross, Jesus' kenosis even unto godless death and descent into hell, and the conviction I have that every hermit must be open to being called to greater reclusion.

Entire Availability for Jesus and for the Hermit:

In light of these, I think for the hermit "my entire availability" means bringing (and maybe relinquishing or actually being stripped of) precisely those discrete gifts which might be used for others, for ministry, for being fruitful in the world. Gifts are the very way we are available to others. Alternately, those ways we are available to others are our truest gifts (including --- when transfigured to mediate the love and mercy of God --- our emptiness and incapacity). This is why a person claiming to be a hermit as a way of refusing to use her gifts or simply failing to be available to others, a way of being selfish and misanthropic, is one of the greatest blasphemies I can think of. But to be stripped of gifts or talents in solitude so that God's redemption is all we "have" is an entirely different thing indeed --- and one which absolutely requires careful and relatively lengthy mutual discernment. In any case, the eremitical life means bringing to God every gift, every potentiality and deficiency one has so that God may do whatever God wishes with them. Eremitical solitude is not about time away so one becomes a better minister (though that may also happen), nor greater degrees of prayer so one's service of others is better grounded (though it will surely do that as well). For those called to these eremitical solitude and commitment to eremitical hiddenness reflect an act of blind trust that affirms whatever God does with one --- even if every individual gift is left unused --- will be ultimately significant in the coming of the Kingdom because in this way God is allowed to be God exhaustively in these lives.

In light of these, I think for the hermit "my entire availability" means bringing (and maybe relinquishing or actually being stripped of) precisely those discrete gifts which might be used for others, for ministry, for being fruitful in the world. Gifts are the very way we are available to others. Alternately, those ways we are available to others are our truest gifts (including --- when transfigured to mediate the love and mercy of God --- our emptiness and incapacity). This is why a person claiming to be a hermit as a way of refusing to use her gifts or simply failing to be available to others, a way of being selfish and misanthropic, is one of the greatest blasphemies I can think of. But to be stripped of gifts or talents in solitude so that God's redemption is all we "have" is an entirely different thing indeed --- and one which absolutely requires careful and relatively lengthy mutual discernment. In any case, the eremitical life means bringing to God every gift, every potentiality and deficiency one has so that God may do whatever God wishes with them. Eremitical solitude is not about time away so one becomes a better minister (though that may also happen), nor greater degrees of prayer so one's service of others is better grounded (though it will surely do that as well). For those called to these eremitical solitude and commitment to eremitical hiddenness reflect an act of blind trust that affirms whatever God does with one --- even if every individual gift is left unused --- will be ultimately significant in the coming of the Kingdom because in this way God is allowed to be God exhaustively in these lives.

When we think of Jesus we see a man whose tremendous potential and capacity for ministry, teaching, preaching, simple availability and community, was stripped away. In part this happened through the circumstances of his birth because he was shamed in this and was seen as less capable of honorable contributions or faithfulness. In part it was because he was a carpenter's son, someone who worked with his hands and was therefore thought of as less intellectually capable. In part it was because he was more and more isolated from his own People and Religion and assumed a peripatetic life with no real roots or sources of honor --- except of course from the One he called Abba. And in part it was because even his miracles and preaching were still insufficient to achieve the transformation of the world, the reconciliation of all things with God so that God might one day truly be all in all. Gradually (or not so gradually once his public ministry began) Jesus was stripped of every individual gift or talent until, nailed to a cross and too physically weak and incapable of anything else, when he was a failure as his world variously measured success, the ONLY thing he could "do" or be was open to whatever God would do to redeem the situation. THIS abject emptiness, which was the measure of his entire availability to God and also to us(!), was the place and way he became truly and fully transparent to his Abba. It also made the effectiveness of his ministry and mission global or even cosmic in scope.

This, it seems to me is really the model of the hermit's life. I believe it is what is called for when The Hermitage Within speaks of the hermit's "entire availability." One traditionalist theology of the cross suggests that Jesus raised himself from godless death to show he was God. The priest I heard arguing this actually claimed there was no other reason for the resurrection! But Paul's and Mark's theologies of the cross say something very different; namely, when all the props are kicked out, when we have nothing left but abject emptiness, when life strips us of every strength and talent and potential, God can and will use this very emptiness as the source of the redemption of all of reality --- if only we give that too to God. Hermits, but especially recluses, are called by God to embrace a similar commitment to kenosis and faith in God. We witness to the power of God at work when perhaps all we can bring is emptiness and "non-accomplishment".

Questions on Active Ministry:

Nothing in this means the non-hermit is not called to use her gifts as best she can. Of course she is called to minister with God, through God, and in God. Her availability to others is meant to be an availability to God and all that is precious to God. We all must spend ourselves in all the ways God calls us to. But old age, illness and other circumstances make some forms of this impossible. When that is true we are called to a greater and different kind of self-emptying, a different kind of availability. We are called to allow God to make of us whatever he wills to do in our incapacity. We are called to witness to the profoundest truth of the Gospel, namely, that not only does our God bring more abundant life out of life and move us from faith to faith but he will bring life out of death, meaning out of absurdity and senselessness, and hope out of the desperate and hopeless situations we each know.

Nothing in this means the non-hermit is not called to use her gifts as best she can. Of course she is called to minister with God, through God, and in God. Her availability to others is meant to be an availability to God and all that is precious to God. We all must spend ourselves in all the ways God calls us to. But old age, illness and other circumstances make some forms of this impossible. When that is true we are called to a greater and different kind of self-emptying, a different kind of availability. We are called to allow God to make of us whatever he wills to do in our incapacity. We are called to witness to the profoundest truth of the Gospel, namely, that not only does our God bring more abundant life out of life and move us from faith to faith but he will bring life out of death, meaning out of absurdity and senselessness, and hope out of the desperate and hopeless situations we each know.

All we can bring to these situations is our entire availability whether measured in talents or incapacity. For Christians our human emptiness is really the greatest form of potential precisely because our God is not only the one who creates out of chaos, but out of nothing at all. Our gifts are wonderful and are to be esteemed and used to serve God and his creation, but what is also true is that our emptiness can actually give God greater scope to be God --- if only we make a gift of it to God for God's own sake. (Remember that whenever we act so that God might be God, which is what I mean by "for God's own sake," there is no limit to who ultimately benefits.) The chronically ill and disabled have an opportunity to witness to this foundational truth with the gift of their lives to God. Hermits, who freely choose the hiddenness of the silence of solitude, I think, witness even more radically to this truth by accepting being freely stripped of every gift --- something they do especially on behalf of all those who are touched by weakness, incapacity, and emptiness --- whenever and for whatever reason these occur.

The Abyss:

You and I have spoken about the "leap into the abyss" in the past and you ask about it specifically so let me add this. For those not part of that conversation let me remind you that I noted that while leaping into the abyss is a fearful thing (i.e., while, for instance, it is an awesome, frightening, exhilarating thing), we don't have to hope God will eventually come to find us there; God is already there. God is the very One who maintains and sustains us in our emptiness and transforms that emptiness into fullness. That is the lesson of Jesus' death, descent, resurrection and ascension. There is no absolutely godless place as a result of Jesus' own exhaustive obedience (openness and responsiveness) to God.

You and I have spoken about the "leap into the abyss" in the past and you ask about it specifically so let me add this. For those not part of that conversation let me remind you that I noted that while leaping into the abyss is a fearful thing (i.e., while, for instance, it is an awesome, frightening, exhilarating thing), we don't have to hope God will eventually come to find us there; God is already there. God is the very One who maintains and sustains us in our emptiness and transforms that emptiness into fullness. That is the lesson of Jesus' death, descent, resurrection and ascension. There is no absolutely godless place as a result of Jesus' own exhaustive obedience (openness and responsiveness) to God.

Yes, I believe the emptiness I have spoken of through this and earlier posts is precisely the abyss which Merton and others speak of. Kenosis is the way we make the leap. The notion of "entire availability" involves a leap (a commitment to self-emptying and stripping) into the depths of that abyss we know as both void (even a relatively godless void) and divine pleroma. (In Jesus' case his consent to enter the abyss of sinful death was consent to enter an absolutely godless void which would be transformed into the fullness of life in and of God). It is first of all the abyss of our own hearts and then (eventually) the abyss of death itself. We ordinarily prepare for the abyss of death to the degree we commit to entering the abyss of our own hearts. Whether we experience mainly profound darkness or the glorious light of Tabor, through our own self-emptying in life and in death we leap securely into God's hands and take up our abode in God's own heart.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:07 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: abyss, chronic illness and disability as vocation, Contemplation and action, Emptiness, kenosis, theology of eremitic life, Theology of the Cross

03 August 2015

A Contemplative Moment: Our Entire Availability

You will always remember how privileged you are that God should love your soul, and as time goes on you will appreciate this all the more. . . . Humble and detached, go into the desert. For God awaiting you there, you bring nothing worth having, except your entire availability. . . .He is calling you to live on friendly terms with him, nothing else.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

9:26 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: A Contemplative Moment

02 August 2015

if everything happens that can't be done (or One Times One)

Forty-five years ago I did a presentation for an English class. As a result I also published my first article in the journal, The Explicator. (That the journal sent me five copies addressed to "Professor Laurel M O'Neal, Department of English" when I had merely been a Sophomore at the college was a real thrill for me!) The presentation involved two poems by e.e. cummings. One of these was "What if a Much of a Which of a Wind". The second was "1 X 1".

Forty-five years ago I did a presentation for an English class. As a result I also published my first article in the journal, The Explicator. (That the journal sent me five copies addressed to "Professor Laurel M O'Neal, Department of English" when I had merely been a Sophomore at the college was a real thrill for me!) The presentation involved two poems by e.e. cummings. One of these was "What if a Much of a Which of a Wind". The second was "1 X 1".

It never occurred to me at that point in my life that this poem might be a description of my vocation much less an explication of what I have been writing about the hiddenness and gift of eremitical life. Still, when I spoke about the sacramental "We" the hermit is to become and witness to in the silence of solitude, I realized I was thinking of this e.e. cummings' poem. It must have resonated with me far more deeply than I realized. Cummings was writing about romantic, erotic love in 1 X 1, but I think it is a wonderful celebration and explication of what I have been struggling to say about union with God, the silence of solitude, and the hiddenness of the eremitical life. After all, sexual love is a reflection of this more fundamental and transcendent union/love.

if everything happens that can't be done

(and anything's righter

than books

could plan)

the stupidest teacher will almost guess

(with a run

skip

around we go yes)

there's nothing as something as one

one hasn't a why or because or although

(and buds know better

than books

don't grow)

one's anything old being everytthing new

(with a what

which

around we come who)

one's everyanything so

so world is a leaf so tree is a bough

(and birds sing sweeter

than books

tell how)

so here is away so your is a my

(with a down

up

around again fly)

forever was never til now

now i love you and you love me

(and books are shuter

than books

can be)

and deep in the high that does nothing but fall

(with a shout

each

around we go all)

there's somebody calling who's we

we're anything brighter than even the sun

(we're everything greater

than books

might mean)

we're everyanything more than believe

(with a spin

leap

alive we're alive)

we're wonderful one times one

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:44 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: e e cummings, Eremitical Hiddenness, if everything happens. . ., One times One

Witnessing to the God who Saves: On Eremitical Hiddenness and Interiority

[[Sister Laurel, when you write, "in every person's life God works

silently in incredible hiddenness," I wonder. Is this what the followers

of Francis de Sales mean by "interiority?" I spoke with [a Sister friend] a

few months ago - and she asked me "How is that interiority coming?" I

didn't know how to answer her, but I thought it might be something like

this.]] (There were other questions included in this email about the

distinction between being the gift and using gifts. Some reflected on the idea of merely being present to others and being gift in that way. I focus on those

here as well.)

[[Sister Laurel, when you write, "in every person's life God works

silently in incredible hiddenness," I wonder. Is this what the followers

of Francis de Sales mean by "interiority?" I spoke with [a Sister friend] a

few months ago - and she asked me "How is that interiority coming?" I

didn't know how to answer her, but I thought it might be something like

this.]] (There were other questions included in this email about the

distinction between being the gift and using gifts. Some reflected on the idea of merely being present to others and being gift in that way. I focus on those

here as well.)Extending this to you and all others it means that should you (or they) never take another person shopping, never make another person smile, never use the gift you are in any way except to allow the God who is faithfulness itself to be faithful to you, THAT is the hiddenness and the gift I am mainly talking about. Yes, it involves the hiddenness of God at work in us but that is the very reason we are gift. We witness to the presence of God in the silence of solitude, in the darkness, in the depths of aloneness, etc. We do that by becoming whole, by becoming loving (something that requires an Other to love us and call us to love), by not going off the rails in solitude and by not becoming narcissists or unbalanced cynics merely turned in on self and dissipated in distraction. We do it by relating to God, by allowing God to be God.

As I noted here recently, I once thought contemplative life and especially eremitic life was a waste

and incredibly selfish. For those authentic hermits the Church professes

and consecrates, and for those authentic lay hermits who live in a hiddenness

only God can and does make sense of, the very thing that made this life

look selfish to me is its gift or charism. It is the solitude of the hermit's life, the absence of others, and even her inability to minister actively to others or use her gifts which God transforms into an ultimate gift. Of course, in coming to understand this, it is terribly

important that we see the "I" of the hermit as the "We" symbolized by

the term "the silence of solitude". It is equally important that we never profess anyone who does not thrive as a human being in this very specific environment. In other words, my life, I think, is meant to

witness starkly and exclusively to the God who makes of an entirely

impoverished "me" a sacramental "We" when I could do nothing at all but allow this to be done in me.

As I noted here recently, I once thought contemplative life and especially eremitic life was a waste

and incredibly selfish. For those authentic hermits the Church professes

and consecrates, and for those authentic lay hermits who live in a hiddenness

only God can and does make sense of, the very thing that made this life