Stillsong Hermitage is a Catholic Hermitage (Canon 603 or Diocesan) in the Camaldolese Benedictine tradition. The name reflects the essential joy and wholeness that comes from a Christ-centered life of prayer in the silence of solitude, and points to the fact that contemplative life -- even that of the hermit -- spills over into witness and proclamation. At the heart of the Church, in the stillness and joy of God's dynamic peace, resonates the song which IS the solitary Catholic hermit.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:50 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Dom Robert Hale -- In Memoriam

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:32 PM

![]()

![]()

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

Thanks for your questions and your very good points. First, let me say I generally agree with you about the ancient hermits you refer to. That is especially true if we are talking about folks like the Desert Mothers and Fathers from @ the 3rd-4th Centuries, the original Carthusians, the Camaldolese, etc. All of these hermits lived eremitical lives of serious asceticism and poverty. The deserts they entered required they make do with what they had at hand and that they live their faith commitments in and through such circumstances. Today the Carthusians continue to live similar lives --- though ordinarily in established Charterhouses with the basic means for healthy lives given to God alone. While people reading the stories of these hermits today might not understand what motivated or motivates them, I think most would find the accounts of their lives and foundations to be powerful witnesses to being driven by something greater than ordinary life seems to provide. One may not understand what moved these hermits but I think most would admire their courage and persistence.

What moves me most when I read or read about these ancient and contemporary hermits is that the hardships they lived, the asceticism they undertook all fade into the background in light of the reasons they undertook these things and their accounts of what they found in their quests. Specifically, the circumstances in which they found themselves did not detract from their eremitical lives, nor were they the focus of these lives; they were a part of the soil in which these lives were fruitful. As a result these hermits (or those who author the accounts we have of their lives) write not primarily about the difficult, even miserable conditions in which they found themselves but about the God who held them securely in spite of these conditions and the struggles they required. More, they do so in ways which are coherent and compelling. In other words, they lived lives faithful to their sense of God's call; they prayed assiduously and worked and grew in their gratefulness to God. They assisted one another, were faithful to a call to solitude and, when a situation was truly unlivable or manifestly unhealthy, they moved on and lived their call elsewhere. So, while asceticism was essential and sometimes simply unavoidable anyway it was the eremitical or "desert life" itself in which one is fulfilled in God which was the focus of their efforts; it is this redemptive content that is the compelling and clear center of their witness --- their living, writing, apothegms, and the accounts of those who write about these hermits.

What moves me most when I read or read about these ancient and contemporary hermits is that the hardships they lived, the asceticism they undertook all fade into the background in light of the reasons they undertook these things and their accounts of what they found in their quests. Specifically, the circumstances in which they found themselves did not detract from their eremitical lives, nor were they the focus of these lives; they were a part of the soil in which these lives were fruitful. As a result these hermits (or those who author the accounts we have of their lives) write not primarily about the difficult, even miserable conditions in which they found themselves but about the God who held them securely in spite of these conditions and the struggles they required. More, they do so in ways which are coherent and compelling. In other words, they lived lives faithful to their sense of God's call; they prayed assiduously and worked and grew in their gratefulness to God. They assisted one another, were faithful to a call to solitude and, when a situation was truly unlivable or manifestly unhealthy, they moved on and lived their call elsewhere. So, while asceticism was essential and sometimes simply unavoidable anyway it was the eremitical or "desert life" itself in which one is fulfilled in God which was the focus of their efforts; it is this redemptive content that is the compelling and clear center of their witness --- their living, writing, apothegms, and the accounts of those who write about these hermits.

The questions I had been asked earlier focused on the role of the diocese in allowing a diocesan (solitary consecrated Catholic) hermit to live in uninhabitable, and even harmful situations or circumstances. What I tried to stress was that a diocese will allow a hermit she has publicly professed to purchase and remodel a house in order to have a hermitage, but that it cannot become a fulltime project which detracts from the hermit's ability to live her Rule or to live a fully and abundantly human life --- especially in the long term. Dioceses can and do allow hermits to build hermitages but they also require prudence in the details. This is only appropriate. Remember that dioceses have to discern the nature and quality of the vocation in front of them; beyond this they must supervise, protect, and nurture such vocations. If an individual is going into substantial debt, living a more and more isolated life, and injuring themselves or exacerbating existing conditions and illnesses needlessly all in the name of creating this "hermitage" then something has gotten skewed, namely, the living of a healthy eremitical life itself has lost its priority and been replaced by concern for one's hermitage itself.

A hermit can make a hermitage of almost any habitable dwelling place. I am thinking now of a chapter written by a Trappist hermit at the Abbey of Gethsemani in KY. (Paul Quenon, OCSO, In Praise of the Useless Life, A Monk's Memoir) In this section devoted to the "Our Golden Age of Hermits" at the Abbey, the author describes the great variety of hermitages found on the Abbey grounds in the years following Thomas Merton's death. Besides Merton's own cinderblock hermitage, hermitages were built in a variety of places out of a variety of materials. Fr. Flavian's was built of cedarwood and was small and isolated but with large small-paned windows taking up most of a couple of walls; Dom James' hermitage (which was designed and built for him after his years of service as Abbot by one of the brothers) was constructed with three wings constructed of steel and glass and cantilevered from a concrete base. The base contained the kitchen, bedroom, and bath, while one wing was the chapel, another a porch and entrance, and a third a living room. As one approached the hermitage from the Abbey all one could see was a pyramid of stone with a slot for a window. (Dom James retired to this hermitage that was a 30 minute drive from the main abbey buildings. He was notably frugal in terms of heating and other expenses, including food; later he was assaulted by intruders and moved back to the abbey infirmary where he would be safe from additional harm.).

A hermit can make a hermitage of almost any habitable dwelling place. I am thinking now of a chapter written by a Trappist hermit at the Abbey of Gethsemani in KY. (Paul Quenon, OCSO, In Praise of the Useless Life, A Monk's Memoir) In this section devoted to the "Our Golden Age of Hermits" at the Abbey, the author describes the great variety of hermitages found on the Abbey grounds in the years following Thomas Merton's death. Besides Merton's own cinderblock hermitage, hermitages were built in a variety of places out of a variety of materials. Fr. Flavian's was built of cedarwood and was small and isolated but with large small-paned windows taking up most of a couple of walls; Dom James' hermitage (which was designed and built for him after his years of service as Abbot by one of the brothers) was constructed with three wings constructed of steel and glass and cantilevered from a concrete base. The base contained the kitchen, bedroom, and bath, while one wing was the chapel, another a porch and entrance, and a third a living room. As one approached the hermitage from the Abbey all one could see was a pyramid of stone with a slot for a window. (Dom James retired to this hermitage that was a 30 minute drive from the main abbey buildings. He was notably frugal in terms of heating and other expenses, including food; later he was assaulted by intruders and moved back to the abbey infirmary where he would be safe from additional harm.).

Br Odilo built a hermitage from scraps from other projects; some monks lived in trailers, one in an old "pig house"; Brother Rene's 16'X8' hermitage was made from the scraps of wood left over after the abbey monks made cheese boxes and it was roofed with corrugated metal; it had neither electricity nor running water but it provided the place where Br Rene could pray and rest in solitude as his own life required. His regular physical needs were taken care of in the abbey itself so the extreme poverty of the hermitage was not problematical in this way. I am also reminded of a contemporary Camaldolese who, in setting up a solitary hermitage, decided to convert a utility shed of the type used today for tools, etc. He rents living space from another person, but the shed is his hermitage and allows him time and space in privacy and solitude; it is snug and comfortable for this use, but it is not habitable and he will spend no time making it so.

Folks hearing the story of any of these hermits would rightly wonder if that story focused on the details of the hermitage, the struggle to build it, the terrible expense and injuries incurred in its building, the hermit's exacerbated chronic pain and illness occasioned by the conditions of his solitude. The point, of course, is that the hermitage itself was of less concern than the call to the silence of solitude and the life of solitary prayer. People find or build a place they can live such a life, but they do not give over years of their lives building the hermitage at the expense of their health or the life they are committed to live in the process. A diocesan hermit's diocese/bishop would never allow this, nor should they I think.

Simplicity? Sacrifice? Asceticism? Frugality? Yes, of course. But these will necessarily involve limitations on the time and energy spent on the hermitage itself. If versions of these are embraced in a way which detracts from one's ability to live the very life they are committed to living, no diocese would or should permit it. Similarly, I also think it is prudent of dioceses to insist that diocesan hermits have a reliable way to support themselves. Dioceses may (but are not required to) assist in times of emergency and temporary need but it is important that the hermit be responsible for her own support and legal decisions --- not least so dioceses are not to be left liable for expenses, injuries, etc., when something untoward happens.

Simplicity? Sacrifice? Asceticism? Frugality? Yes, of course. But these will necessarily involve limitations on the time and energy spent on the hermitage itself. If versions of these are embraced in a way which detracts from one's ability to live the very life they are committed to living, no diocese would or should permit it. Similarly, I also think it is prudent of dioceses to insist that diocesan hermits have a reliable way to support themselves. Dioceses may (but are not required to) assist in times of emergency and temporary need but it is important that the hermit be responsible for her own support and legal decisions --- not least so dioceses are not to be left liable for expenses, injuries, etc., when something untoward happens.

Again, this is all about living and protecting a vocation which is a gift of God. Not all historical forms of asceticism have been edifying, nor have all forms of suffering or isolation. It seems to me that we are more sensitive today to what are healthy forms of these, or what are forms which speak primarily of redemption rather than of sin/brokenness; it also seems to me that the Church, in approving certain eremitical vocations and disapproving others demonstrates this sensitivity and insists that canonical or public eremitical vocations witness to the redemption that comes to each of us through and in Christ. I hope this is of assistance to you.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:10 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: asceticism, Canon 603 - false solitude

At the end of about a year (the groom's Father makes sure his Son does not do a haphazard job on the new addition just so he can get to his bride sooner!), on a day and at an hour the bride does not know, the groom comes with his friends. They bear torches, blow the shofar, and announce, "The Bridegroom comes" --- just as we hear in Friday's Gospel. The bride's attendants come forth with their own lamps and, with the entire town, accompany her to her new home. The marriage of this bride and groom symbolizes (in the strongest sense of that term) the marriage of God to his people achieved on Sinai. Thus, the service the bridesmaids and groomsmen do for these friends is also a service they do for Israel and a witness to God's ineffable mercy and covenant faithfulness.

At the end of about a year (the groom's Father makes sure his Son does not do a haphazard job on the new addition just so he can get to his bride sooner!), on a day and at an hour the bride does not know, the groom comes with his friends. They bear torches, blow the shofar, and announce, "The Bridegroom comes" --- just as we hear in Friday's Gospel. The bride's attendants come forth with their own lamps and, with the entire town, accompany her to her new home. The marriage of this bride and groom symbolizes (in the strongest sense of that term) the marriage of God to his people achieved on Sinai. Thus, the service the bridesmaids and groomsmen do for these friends is also a service they do for Israel and a witness to God's ineffable mercy and covenant faithfulness. Similarly waiting on others is not always easy either. Wait staff in restaurants sometimes resent the very guests they are meant to serve; work keeps them from their "real lives". And some of these wait staff take it out on those they are meant to serve. Whether this means allowing some to go unserved while waiters talk on cell phones, or arguing with and blaming customers, or actually doctoring the dishes served at the table, putting nasty comments on the bill, etc. waiting on others can be challenging and demanding; our own inability to wait on God is an important reason we fail to pray as we are called to. We may fail at this out of ignorance; we may not know prayer is about putting ourselves at God's disposal rather than expecting God to be at ours. We may be unwilling or resistant to putting ourselves at God's disposal or to order our lives around this relationship as fully as we know we ought.

Similarly waiting on others is not always easy either. Wait staff in restaurants sometimes resent the very guests they are meant to serve; work keeps them from their "real lives". And some of these wait staff take it out on those they are meant to serve. Whether this means allowing some to go unserved while waiters talk on cell phones, or arguing with and blaming customers, or actually doctoring the dishes served at the table, putting nasty comments on the bill, etc. waiting on others can be challenging and demanding; our own inability to wait on God is an important reason we fail to pray as we are called to. We may fail at this out of ignorance; we may not know prayer is about putting ourselves at God's disposal rather than expecting God to be at ours. We may be unwilling or resistant to putting ourselves at God's disposal or to order our lives around this relationship as fully as we know we ought.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:43 PM

![]()

![]()

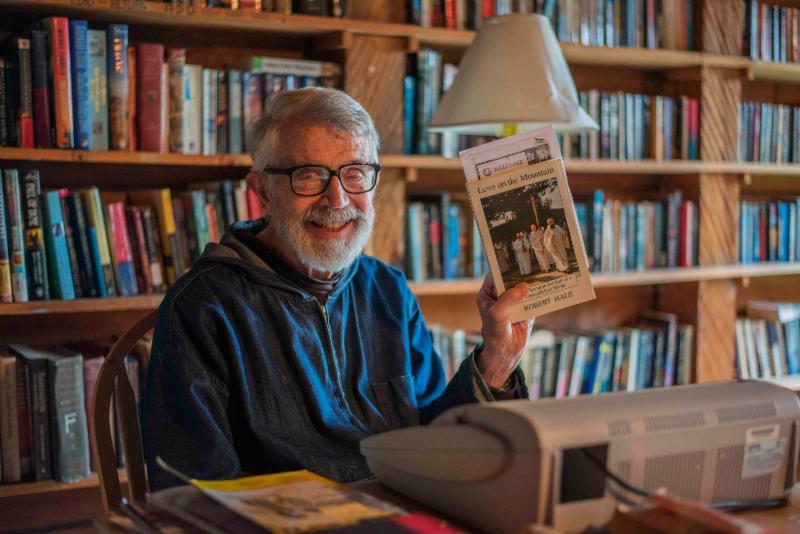

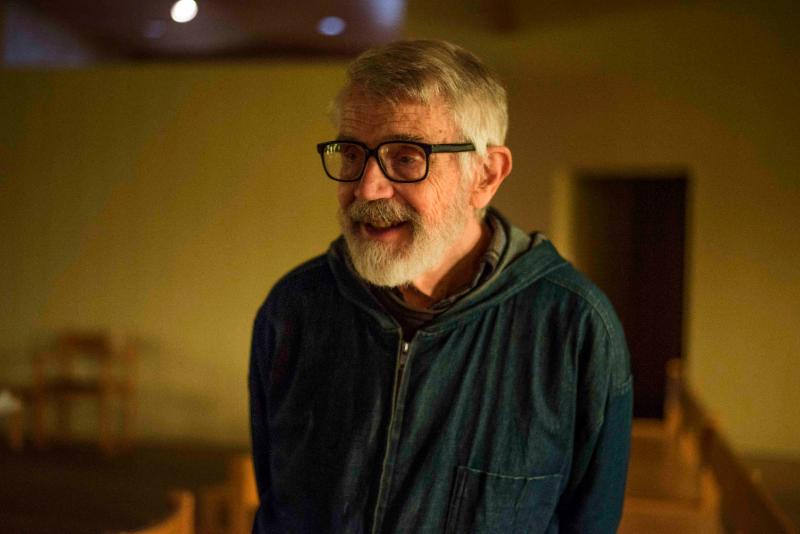

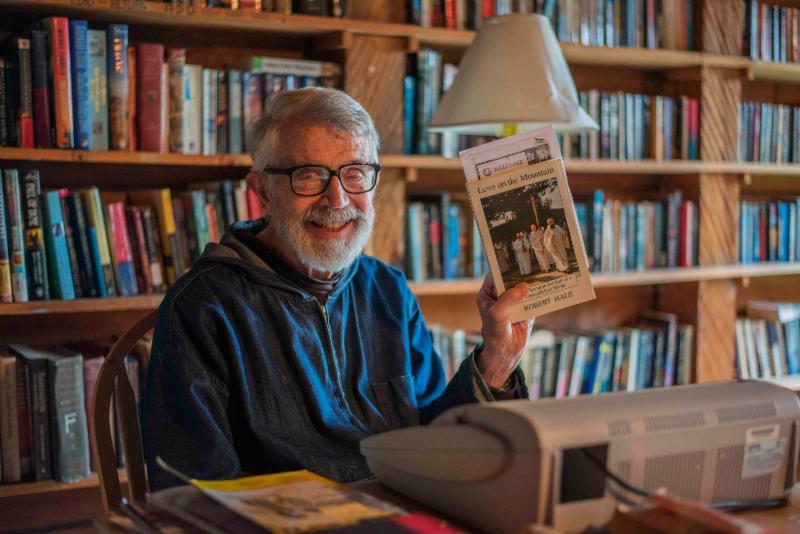

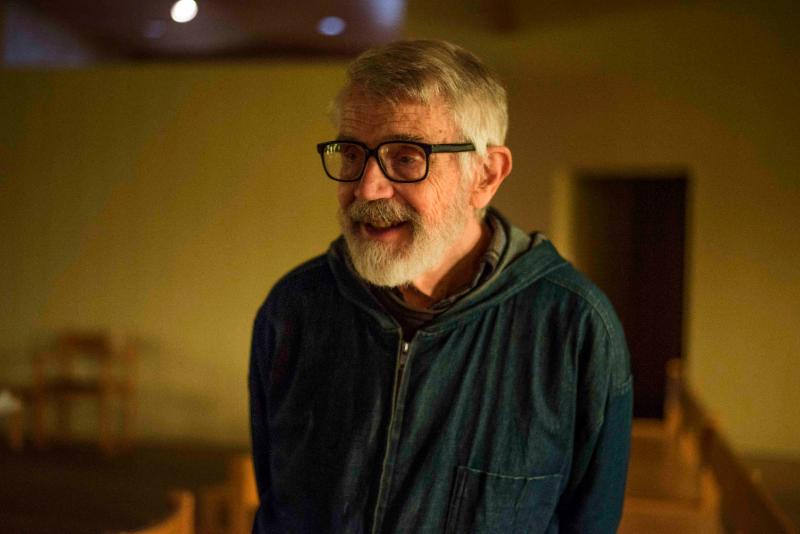

When I was first becoming a diocesan hermit Father Robert read my proposed Rule and gave me suggestions --- mainly an encouragement that I build in enough time for rest. For those who have not already done so I recommend reading Dom Robert's, Love on the Mountain, the Chronicle Journal of a Camaldolese Monk. Written while Robert was Prior it is a touching, often humorous autobiographical account of his community's life as Camaldolese in Big Sur. I have mentioned this before but do so again since I am rereading it as part of keeping Dom Robert in prayer.

When I was first becoming a diocesan hermit Father Robert read my proposed Rule and gave me suggestions --- mainly an encouragement that I build in enough time for rest. For those who have not already done so I recommend reading Dom Robert's, Love on the Mountain, the Chronicle Journal of a Camaldolese Monk. Written while Robert was Prior it is a touching, often humorous autobiographical account of his community's life as Camaldolese in Big Sur. I have mentioned this before but do so again since I am rereading it as part of keeping Dom Robert in prayer.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:58 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Dom Robert Hale, Love on the Mountain

Today's Gospel is one of my all-time favorite parables, that of the laborers in the vineyard. The story is simple --- deceptively so in fact: workers come to work in the vineyard at various parts of the day all having contracted with the master of the vineyard to work for a day's wages. Some therefore work the whole day, some are brought in to work only half a day, and some are hired only when the master comes for them at the end of the day. When time comes to pay everyone what they are owed those who came in to work last are paid first and receive a full day's wages. Those who came in to work first expect to be paid more than these, but are disappointed and begin complaining when they are given the same wage as those paid first. The response of the master reminds them that he has paid them what they contracted for, nothing less, and then asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own money. A saying is added: [in the Kingdom of God] the first shall be last and the last first.

Today's Gospel is one of my all-time favorite parables, that of the laborers in the vineyard. The story is simple --- deceptively so in fact: workers come to work in the vineyard at various parts of the day all having contracted with the master of the vineyard to work for a day's wages. Some therefore work the whole day, some are brought in to work only half a day, and some are hired only when the master comes for them at the end of the day. When time comes to pay everyone what they are owed those who came in to work last are paid first and receive a full day's wages. Those who came in to work first expect to be paid more than these, but are disappointed and begin complaining when they are given the same wage as those paid first. The response of the master reminds them that he has paid them what they contracted for, nothing less, and then asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own money. A saying is added: [in the Kingdom of God] the first shall be last and the last first.

Now, it is important to remember what the word parable means in appreciating what Jesus is actually doing with this story and seeing how it challenges us today. The word parable, as I have written before, comes from two Greek words, para meaning alongside of and balein, meaning to throw down. What Jesus does is to throw down first one set of values -- one well-understood or common-perspective --- and allow people to get comfortable with that. (It is one they understand best so often Jesus merely needs to suggest it while his hearers fill in the rest. For instance he mentions a sower, or a vineyard and people fill in the details. Today he might well speak of a a CEO in an office, or a mother on a run to pick up kids from a swim meet or soccer practice.) Then, he throws down a second set of values or a second way of seeing reality which disorients and gets his hearers off-balance.

This second set of values or new perspective is that of the Kingdom of God. Those who listen have to make a decision. (The purpose of the parable is not only to present the choice, but to engage the reader/hearer and shake them up or disorient them a bit so that a choice for something new can (and hopefully will) be made.) Either Jesus' hearers will reaffirm the common values or perspective or they will choose the values and perspective of the Kingdom of God. The second perspective, that of the Kingdom is often counterintuitive, ostensibly foolish or offensive, and never a matter of "common sense". To choose it --- and therefore to choose Jesus and the God he reveals --- ordinarily puts one in a place which is countercultural and often apparently ridiculous.

So what happens in today's Gospel? Again, Jesus tells a story about a vineyard and a master hiring workers. His readers know this world well and despite Jesus stating specifically that each man hired contracts for the same wage, common sense says that is unfair and the master MUST pay the later workers less than he pays those who came early to the fields and worked through the heat of the noonday sun. And of course, this is precisely what the early workers complain about to the master. It is precisely what most of US would complain about in our own workplaces if someone hired after us got more money, for instance, or if someone with a high school diploma got the same pay and benefit package as someone with a doctorate --- never mind that we agreed to this package! The same is true in terms of religion: "I spent my WHOLE life serving the Lord. I was baptized as an infant and went to Catholic schools from grade school through college and this upstart convert who has never done anything at all at the parish gets the Pastoral Associate job? No Way!! No FAIR!!" From our everyday perspective this would be a cogent objection and Jesus' insistence that all receive the same wage, not to mention that he seems to rub it in by calling the last hired to be paid first (i.e., the normal order of the Kingdom), is simply shocking.

And yet the master brings up two points which turn everything around: 1) he has paid everyone exactly what they contracted for --- a point which stops the complaints for the time being, and 2) he asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own gifts or money. He then reminds his hearers that the first shall be last, and the last first in the Kingdom of God. If someone was making these remarks to you in response to cries of "unfair" it would bring you up short, wouldn't it? If you were already a bit disoriented by a pay master who changed the rules of commonsense this would no doubt underscore the situation. It might also cause you to take a long look at yourself and the values by which you live your life. You might ask yourself if the values and standards of the Kingdom are really SO different than those you operate by everyday of your life, not to mention, do you really want to "buy into" this Kingdom if the rewards are really parcelled out in this way, even for people less "gifted" and less "committed" than you consider yourself! Of course, you might not phrase things so bluntly. If you are honest, you will begin to see more than your own brilliance, giftedness, or commitedness; You might begin to see these along with a deep neediness, a persistent and genuine fear at the cost involved in accepting this "Kingdom" instead of the world you know and have accommodated yourself to so well.

And yet the master brings up two points which turn everything around: 1) he has paid everyone exactly what they contracted for --- a point which stops the complaints for the time being, and 2) he asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own gifts or money. He then reminds his hearers that the first shall be last, and the last first in the Kingdom of God. If someone was making these remarks to you in response to cries of "unfair" it would bring you up short, wouldn't it? If you were already a bit disoriented by a pay master who changed the rules of commonsense this would no doubt underscore the situation. It might also cause you to take a long look at yourself and the values by which you live your life. You might ask yourself if the values and standards of the Kingdom are really SO different than those you operate by everyday of your life, not to mention, do you really want to "buy into" this Kingdom if the rewards are really parcelled out in this way, even for people less "gifted" and less "committed" than you consider yourself! Of course, you might not phrase things so bluntly. If you are honest, you will begin to see more than your own brilliance, giftedness, or commitedness; You might begin to see these along with a deep neediness, a persistent and genuine fear at the cost involved in accepting this "Kingdom" instead of the world you know and have accommodated yourself to so well.

You might consider too, and carefully, that the Kingdom is not an otherwordly heaven, but that it is the realm of God's sovereignty which, especially in Christ, interpenetrates this world, and is actually the goal and perfection of this world; when you do, the dilemma before you gets even sharper. There is no real room for opting for this world's values now in the hope that those "other Kingdomly values" only kick in after death! All that render to Caesar stuff is actually a bit of a joke if we think we can divvy things up neatly and comfortably (I am sure Jesus was asking for the gift of one's whole self and nothing less when he made this statement!), because after all, what REALLY belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God? No, no compromises are really allowed with today's parable, no easy blending of the vast discrepancy between the realm of God's sovereignty and the world which is ordered to greed, competition, self-aggrandizement and hypocrisy, nor therefore, to the choice Jesus puts before us.

So, what side will we come down on after all this disorientation and shaking up? I know that every time I hear this parable it touches a place in me (yet another one!!) that resents the values and standards of the Kingdom and that desires I measure things VERY differently indeed. (Today after Mass, one friend said he thought the reading was contrary to his sense of social justice, so I am not alone here!) It may be a part of me that resists the idea that everything I have and am is God's gift, even if I worked hard in cooperating with that (my very capacity and willingness to cooperate are ALSO gifts of God!). It may be a part of me that looks down my nose at this person or that and considers myself better in some way (smarter, more gifted, a harder worker, stronger, more faithful, born to a better class of parents, etc, etc). It may be part of me that resents another's wage or benefits despite the fact that I am not really in need of more myself. It may even be a part of me that resents my own weakness and inabilities, my own illness and incapacities which lead me to despise the preciousness and value of my life and his own way of valuing it which is God's gift to me and to the world. I am socialized in this first-world-culture and there is no doubt that it resides deeply and pervasively within me contending always for the Kingdom of God's sovereignty in my heart and living. I suspect this is true for most of us, and that today's Gospel challenges us to make a renewed choice for the Kingdom in yet another way or to another more profound or extensive degree.

For Christians every day is gift and we are given precisely what we need to live fully and with real integrity if only we will choose to accept it (and I say this as someone who has known certain kinds of severe deprivation as I grew up, it is not a naïve or Pollyannaish kind of statement but one rooted in faith in what God has revealed to me during the past years.). We are precious to God, and this is often hard to really accept, but neither more nor less precious than the person standing in the grocery store line ahead of us or folded dirty and disheveled behind a begging sign on the street corner near our bank or outside our favorite coffee shop. The wage we have agreed to (or been offered) is the gift of God's very self along with his judgment that we are indeed precious, and so, the free and abundant but cruciform life of a shared history and destiny with that same God whose characteristic way of being is kenotic. He pours himself out with equal abandon for each of us whether we have served him our whole lives or only just met him this afternoon. He does so whether we are well and whole, or broken and feeble. And he asks us to do the same, to pour ourselves out similarly both for his own sake and for the sake of his creation-made-to-be God's Kingdom.

To do so means to decide for his reign now and tomorrow and the day after that; it means to accept his gift of Self as fully as he wills to give it, and it therefore means to listen to him and his Word so that we MAY be able to decide and order our lives appropriately in his gratuitous love and mercy. The parable in today's Gospel is a gift which makes this possible --- if only we would allow it to work as Jesus empowers and wills it!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:27 AM

![]()

![]()

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I was reading Catholic Hermit: Time to Praise among other related posts on this blog, and I wondered how a diocese could allow a hermit to live in substandard living conditions for years at a time. I also wondered how they could let a consecrated Catholic hermit spend the majority of her time re-habbing an old farmhouse to use as a hermitage and then to just move on to somewhere else (she says in another post that place may have to be a shelter!) when the rehab is finished. What raised questions for me is this hermit's description of living an essentially unbalanced eremitical life of physical labor she is ill-equipped for and which increased her own chronic pain, led to or worsened unnecessary injuries and unanticipated expenses --- all without assistance or support of any kind from her diocese. Is this typical? It seems unconscionable that a diocese could treat a hermit this way --- without guidance or assistance in housing even to the point of allowing the hermit to write about maybe needing to go to a shelter lest they be "homeless" and out on the streets. How could a diocese allow this? It all reflects badly on them -- the Church I mean. What am I missing?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I was reading Catholic Hermit: Time to Praise among other related posts on this blog, and I wondered how a diocese could allow a hermit to live in substandard living conditions for years at a time. I also wondered how they could let a consecrated Catholic hermit spend the majority of her time re-habbing an old farmhouse to use as a hermitage and then to just move on to somewhere else (she says in another post that place may have to be a shelter!) when the rehab is finished. What raised questions for me is this hermit's description of living an essentially unbalanced eremitical life of physical labor she is ill-equipped for and which increased her own chronic pain, led to or worsened unnecessary injuries and unanticipated expenses --- all without assistance or support of any kind from her diocese. Is this typical? It seems unconscionable that a diocese could treat a hermit this way --- without guidance or assistance in housing even to the point of allowing the hermit to write about maybe needing to go to a shelter lest they be "homeless" and out on the streets. How could a diocese allow this? It all reflects badly on them -- the Church I mean. What am I missing?]]

Introduction, Continuing Questions Regarding the Blog/Blogger Cited

Thank you for your questions. I will not pull punches here. I am more than a little frustrated by similar questions and by the situation which prompts them because again and again this particular blogger is responsible for confusing those who come to her blog after googling, "Catholic hermit". How ever good her reasons or motivations are, she is misrepresenting a significant vocation with her own eccentric way of living and inaccurate way of describing herself.

Thank you for your questions. I will not pull punches here. I am more than a little frustrated by similar questions and by the situation which prompts them because again and again this particular blogger is responsible for confusing those who come to her blog after googling, "Catholic hermit". How ever good her reasons or motivations are, she is misrepresenting a significant vocation with her own eccentric way of living and inaccurate way of describing herself.

However, also according to her own blogging she is not a consecrated Catholic hermit when these terms are used in the way the Roman Catholic Church uses them. So, before I answer the questions you have asked about hermits and the responsibility of dioceses let me say once again, the author of the blog you cited is a Catholic laywoman and hermit with private vows. Her lay vocation is to be esteemed but she is responsible for her life in the way any other lay person is; the Church has not initiated her into the consecrated state and for this reason the local Church/bishop, et al, are not responsible for her in the limited way the church/bishop would be for a publicly professed/consecrated hermit.

The Real Question: The Church's Exercise of Responsibility in Regard to Those She Consecrates

Your questions, while triggered by this person's situation, are more about the Church's exercise of responsibility in regard to those she consecrates as hermits, so let me speak more specifically to these. My own sense is a Catholic (specifically a c 603) hermit's living circumstances are overseen by her bishop and delegate. (Hermits who belong to canonical institutes live their lives under the supervision of leadership in that institute.) My own delegate, for instance, understands her role as helping ensure that the life I live is a healthy one, one leading to human wholeness, holiness, and representing the best eremitical life calls for and calls forth from me for the sake of the Church and world. I keep her apprised of my spiritual life, of course, but it also means that generally speaking she is aware of my physical health and the way I live my life both in this hermitage and in my parish. She is similarly aware of my significant relationships (friendships and professional), work, intellectual pursuits, the things I do for recreation or creative outlets, and the contents of the Rule by which I live my life. (All of these concerns are my own responsibility but my delegate assists me as needed both for my own sake, and for the sake of the vocation to eremitical life itself. She does this on my behalf as well as on behalf of the local and universal Church.)

Temporary situations may cause a certain imbalance in a hermit's life. Medical situations may mean she needs assistance with personal care, trips to the doctor's, etc, for a period of several weeks or even a few months. However, living situations which are substandard as described on the "Catholic Hermit" blog and cannot be rectified in a reasonable time (several months) at an expense the hermit can truly afford would not be allowed, not least because both the hermit's health and vocation are threatened by them.

Temporary situations may cause a certain imbalance in a hermit's life. Medical situations may mean she needs assistance with personal care, trips to the doctor's, etc, for a period of several weeks or even a few months. However, living situations which are substandard as described on the "Catholic Hermit" blog and cannot be rectified in a reasonable time (several months) at an expense the hermit can truly afford would not be allowed, not least because both the hermit's health and vocation are threatened by them.

While a diocese does not subsidize any hermitage a diocesan hermit buys, the diocese does have the right to expect the canonical hermit to make prudent investments of time, money, and energy with the help of knowledgeable professionals (realtors, attorneys, bankers, etc). Should the diocesan hermit make a bad financial investment and be caught in a situation like that described in the blog you cited (inadequate medical care, insufficient hygiene and access to personal necessities like toilets and showers, dangerous vermin-ridden living conditions, inadequate conditions for food preparation and storage, insufficient financial resources, etc.) they would have the right to expect the hermit to find a way out of the situation within a reasonable period of time. If she needed assistance in this a diocese could be expected to try to find people (or help the hermit locate people) who can offer some assistance but the overall responsibility remains the hermit's own. However, let it be noted, a hermit's extended inability to live his/her Rule of life might well mean, for example, the diocese will eventually need to dispense the hermit's vows.

I don't believe any diocese would allow a publicly professed hermit to buy a house to fix up as a hermitage if that project was going to take five years and more of apparently full-time effort by the hermit herself; they would especially not allow it if the hermit was merely going to sell the property at the end of that time and had nowhere to go after this. (Dioceses of course can (and do) allow a hermit to build or remodel a hermitage, but they have a right and even an obligation to set limits in terms of finances, time frames, living conditions, and so forth. The life is a contemplative one, after all; it is a healthy one and needs to be stably established. A diocese might also put off admittance to new stages of the life until a person is finished with the project and can truly live their eremitical life consistently and fully. If such a project was approved or allowed and was projected to take a year or two, a diocese might wait until its completion to admit one to perpetual profession and consecration, for instance.)

A fulltime long-term building situation would become even more objectionable if those five years involved insufficient professional assistance (skilled carpenters, licensed plumbers, electricians, etc) or skill which led to numerous injuries linked to accidents with power tools the hermit was incompetent to wield skillfully. After all, the prudential witness value of such a life is dubious; going it entirely alone when this leads to personal harm is not really typical of eremitical life nor does it witness to a stable state of life lived under a vow of religious poverty. Moreover, since it means the long-term suspension of the hermit's Rule for insufficient reasons, it lacks integrity. While dioceses allow hermits to choose and finance their own living arrangements according to what is allowed by religious poverty and their own budgets, and while manual labor is certainly permissible and even essential to the life, that hermit must be able to live her Rule in the midst of any building and re-habilitating. Some temporary adjustments in this can be made, just as may occur in times of illness or injury, of course, but these are worked out under the supervision of directors, delegates, and (sometimes) the hermit's bishop.

Most of your questions about the diocese's behavior presume the author of the blog you cited is really a Catholic hermit who is publicly admitted to the consecrated state of life and all the rights and obligations thereto. Most of them also dissolve once it is made clear this person is NOT publicly professed or consecrated and has not been entrusted with nor accepted the rights and obligations of living eremitical life in the name of the Church. Still, no, this situation is not typical!

Most of your questions about the diocese's behavior presume the author of the blog you cited is really a Catholic hermit who is publicly admitted to the consecrated state of life and all the rights and obligations thereto. Most of them also dissolve once it is made clear this person is NOT publicly professed or consecrated and has not been entrusted with nor accepted the rights and obligations of living eremitical life in the name of the Church. Still, no, this situation is not typical!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:23 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Catholic Hermit blogger, disability as vocation, Joyful hermit speaks

Please note, the readings referenced below differ from today's but I hope this reprise is still of value!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:35 PM

![]()

![]()

|

| Transfiguration by Lewis Bowman |

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:29 AM

![]()

![]()

|

|