[[Dear Sister O'Neal, I thought your reference to forms of "personal noisiness" in your post on the destructiveness of physical solitude was intriguing. You said, [[ The personal "noisiness" (physical, emotional, and spiritual) of your isolation is NOT what canon 603 is talking about when it refers to the silence of solitude.]] Could you please say more about this? I am used to thinking of external and inner silence and solitude but I have never thought in terms of "personal noisiness" as being contrary to the solitude of a hermit. Makes sense though.]]

[[Dear Sister O'Neal, I thought your reference to forms of "personal noisiness" in your post on the destructiveness of physical solitude was intriguing. You said, [[ The personal "noisiness" (physical, emotional, and spiritual) of your isolation is NOT what canon 603 is talking about when it refers to the silence of solitude.]] Could you please say more about this? I am used to thinking of external and inner silence and solitude but I have never thought in terms of "personal noisiness" as being contrary to the solitude of a hermit. Makes sense though.]]

I have written here before about human beings as language events and I may once have referred to times in our lives when we are screams of anguish rather than articulate words. I have also written in the past about not only the Word becoming flesh, but flesh becoming word in Christ. (When this occurs a person becomes authentically human and a living embodiment of the Gospel of God.) When I wrote the comment you cited I was thinking about someone I experience or perceive as a scream of anguish and often, one of outright despair. A person who has reached such a place in their lives seems to me to be "noisy" rather in the way Pigpen carries a ubiquitous cloud of dust around himself. Their pain and whatever else is part of the anguished "scream" they are oozes out of them no matter what they do. Even sitting silently in prayer or other pious practices may be about or at least involve calling attention to themselves and their needs. The problem with a scream is that it cannot be tolerated by others for long; it calls attention to one's pain and anguish and people will initially try to assist the anguished person in some way but it also pushes people away --- not only because they cannot communicate with the one in pain to determine what is needed, but because it leaves them truly helpless to resolve this in any meaningful way.

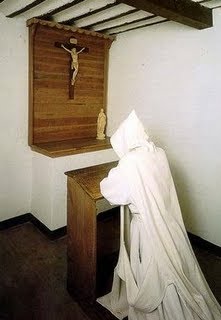

When I write, therefore, about "the silence of solitude" I am speaking first of all of the physical environment of the hermitage. The normal "air" a hermit breathes is first of all that of the physical silence of being alone. But it is far more than this as well. On another level it involves being silent with God, listening to and for God, learning to attune oneself to the voice of God both within one's heart and in the various other ways that voice comes to one in solitude.

When I write, therefore, about "the silence of solitude" I am speaking first of all of the physical environment of the hermitage. The normal "air" a hermit breathes is first of all that of the physical silence of being alone. But it is far more than this as well. On another level it involves being silent with God, listening to and for God, learning to attune oneself to the voice of God both within one's heart and in the various other ways that voice comes to one in solitude.

Scripture, Eucharist, silent prayer, spiritual direction, friends and parishioners at Mass and those special times when the hermit socializes or recreates with these important people in her life --- all of these are ways God speaks to the hermit in her solitude; the silence of solitude here refers to the absence of distractions from this dialogue between oneself and God as well as to one's commitment to refrain from unnecessary distractions (some recreation is necessary to the vitality of the dialogue). On a final level then, the silence of solitude refers to what is created within the hermit, or better put perhaps, it refers to the person (hermit) who is created by the dialogue with God in the hermitage. This is what I referred to when I spoke of shalom, or the wholeness, peace, and joy that is the fruit of an eremitical life. Much of the "noisiness" of human yearning and striving is silenced; so is the scream of self-centeredness and the inability to listen to or hear others. One is at peace with God and with oneself; one is at home with God wherever one goes.

In the past I have also said that the silence of solitude is the environment, the goal, and the charism of eremitical life. What I have just described in the above paragraph is what I mean by environment and goal. When a person is made whole in solitude, when their life breathes (sings!) a resultant sense of peace and the security, joy, and rich meaning of communion with God, then that life is also a gift to the Church and world. This gift (charisma) is what canon 603 calls the silence of solitude; it contrasts radically with the personal noisiness that is linked to the alienation and brokenness of sin. It reminds us all of the completeness we are called to in God. But this is not achieved in the hermit's cell for one not called to eremitical solitude. Instead the personal disintegration which is already present is exacerbated and the scream of anguish one was (if in fact that was the case!) becomes either more explicit or more strident, more expressive of neediness and greater self-centeredness, as well as becoming even less edifying for others. In such a case flesh (sinful existence) remains scream and never rises to the level of Word (graced and articulate existence); that is, one never effectively proclaims the Gospel with one's very life nor reaches the goal of the silence of solitude (the silent dialogical reality we are in union with God) either. Instead the false self and one's own woundedness remain the center of one's life and the content of one's putative 'message'.

I hope this serves as a beginning to explaining my reference to "personal noisiness."

Rilke’s Book of Hours, I, 17

She who reconciles the ill-matched threads

of her life, and weaves them gratefully

into a single cloth-

it’s she who drives the loudmouths from the hall

and clears it for a different celebration

where the one guest is you.

In the softness of evening

it’s you she receives.

You are the partner of her loneliness,

the unspeaking center of her monologues.

With each disclosure you encompass more

and she stretches beyond what limits her,

to hold you.

~Rainer Maria Rilke,

translated by Anita Barrows & Joanna Macy