Today's Gospel brought us face to face with who we are called to be, and with the results of the idolatry that occurs whenever we refuse that vocation. Both issues, vocation and true worship are rooted in the Scriptural notion of obedience, that is in the obligation which is our very nature, to hearken --- to listen and respond to God appropriately with our whole selves. When we are empowered to and respond with such obedience our very lives proclaim the Kingdom of God, not as some distant reality we are still merely waiting for, but as something at work in us here and now. In fact, when our lives are marked by this profound dynamic of obedience, today's readings remind us the reign of God cannot be hidden from others --- though its presence will be seen only with the eyes of faith.

Today's Gospel brought us face to face with who we are called to be, and with the results of the idolatry that occurs whenever we refuse that vocation. Both issues, vocation and true worship are rooted in the Scriptural notion of obedience, that is in the obligation which is our very nature, to hearken --- to listen and respond to God appropriately with our whole selves. When we are empowered to and respond with such obedience our very lives proclaim the Kingdom of God, not as some distant reality we are still merely waiting for, but as something at work in us here and now. In fact, when our lives are marked by this profound dynamic of obedience, today's readings remind us the reign of God cannot be hidden from others --- though its presence will be seen only with the eyes of faith.

In the Gospel, (Mark 7:31-37) A man who is deaf and also has a resultant speech impediment is brought by friends to Jesus; Jesus is begged to heal him. In what is an unusual process for Mark (or for any of the Gospel writers) in its crude physicality, Jesus puts his fingers in the man's ears, and then, spitting on his fingers, touches the man's tongue. He looks up to heaven, groans, and says in Aramaic, "ephphatha!" (that is, "Be opened!"). Immediately the man is healed and "speaks plainly." Those who brought him to Jesus are astonished, joyful, and could not contain their need to proclaim Jesus and what he had done: "He has done all things well. He makes the deaf hear and the mute speak."

I am convinced that the deaf and "mute" man (for he is not really mute, but impeded from clear speech by his inability to hear) is a type of each of us, a symbol for the persons we are and for the vocation we are each called to. Theologians speak of human beings as "language events." We are called to be by God, conceived from and an expression of the love of two people for one another, named so that we have the capacity for personal presence in the world and may be personally addressed by others; we are shaped for good or ill, for wholeness or woundedness, by every word which is addressed to us. Language is the means and symbol of our capacity for relationship and transcendence.

Consider how it is that vocabulary of all sorts opens various worlds to us and makes the whole of the cosmos our own to understand, wonder at, and render more or less articulate; consider how a lack of vocabulary whether affective, theological, scientific, mathematical, musical, psychological, etc, can cripple us and distance us from effectively relating to various dimensions of human life including our own heart. Note, for instance that physicians have found that in any form of mental illness there is a corresponding dimension of difficulty with or dysfunction of language. Consider the very young child's wonderful (and often really annoying!) incessant questioning. There, with every single question and answer, language mediates transcendence (a veritable explosion of transcendence in fact!) and initiates the child further and further into the world of human community, knowledge, understanding, reflection, celebration, and commitment. Language marks us as essentially communal, fundamentally dependent upon others to call us beyond ourselves, essentially temporal AND transcendent, and, by virtue of our being imago dei, responsive and responsible (obedient) at the core of our existence.

One theologian (Gerhard Ebeling), in fact, notes that the most truly human thing about us is our addressiblity and our ability to address others. Addressibility includes and empowers responsiveness; that is, it has both receptive and expressive dimensions. It is the characteristically human form of language which creates community. It marks us as those whose coming to be is dependent upon the dynamic of obedience --- but also on the generosity of those who would address us and give us a place to stand as persons --- places we cannot assume on our own. We spend our lives responsively -- coming (and often struggling) to attend to and embody or express more fully the deepest potentials within us in myriad ways and means and doing so as an answer to the invitation of God's very personal call and other's love for us.

But a lot can hinder this most foundational vocational accomplishment. Sometimes our own woundedness prevents the achievement of this goal to greater degrees. Sometimes we are not given the tools or education we need to develop this capacity. Sometimes, we are badly or ineffectually loved and rendered relatively deaf and "mute" in the process. Oftentimes we muddle the clarity of that expression through cowardice, ignorance, or even willful disregard. Our hearts, as I have noted here before, are dialogical realities. That is, they are the place where God bears witness to himself, the event marked in a defining way by God's continuing and creative address and our own embodied response. In every way our lives are either an expression of the Word or logos of God which glorifies (him), or they are, to whatever extent, a dishonoring evasion, distortion, or even an outright lie.

And so, faced with a man who is crippled in so many fundamental ways --- one, that is, for whom the world of community, knowledge, and celebration is largely closed by disability, Jesus prays to God, touches, and addresses the man directly, "Ephphatha!" ---Be thou opened!" It is the essence of what Christians refer to as salvation, the event in which a word of command and power heals the brokennesses which cripple and isolate, and which, by empowering obedience reconciles the man to himself, his God, his people and world. As a result of Jesus' Word, and in response, the man speaks plainly --- for the first time (potentially) transparent to himself and to those who know him; he is more truly a revelatory or language event, authentically human and capable through the grace of God of bringing others to the same humanity through direct response and address.

And so, faced with a man who is crippled in so many fundamental ways --- one, that is, for whom the world of community, knowledge, and celebration is largely closed by disability, Jesus prays to God, touches, and addresses the man directly, "Ephphatha!" ---Be thou opened!" It is the essence of what Christians refer to as salvation, the event in which a word of command and power heals the brokennesses which cripple and isolate, and which, by empowering obedience reconciles the man to himself, his God, his people and world. As a result of Jesus' Word, and in response, the man speaks plainly --- for the first time (potentially) transparent to himself and to those who know him; he is more truly a revelatory or language event, authentically human and capable through the grace of God of bringing others to the same humanity through direct response and address.

Our own coming to wholeness, to a full and clear articulation of our truest selves is a communal achievement. Even (or even especially) in the lives of hermits this has always been true insofar as solitude is NOT isolation but is instead a form of communion marked by profound dependence on the Word of God and lived specifically for the salvation of others. In today's gospel friends bring the man to Jesus, Jesus prays to God before acting to heal him. The presence of friends is another sign not only of the man's nature as made-for-communion and the fact that none of us come to language (or, that is, to the essentially human capacity for responsiveness or obedience) alone, but similarly, of the deaf man's total inability to approach Jesus on his own. At the same time, Jesus takes the man aside and what happens to him in this encounter is thus signaled to be profoundly personal, intimate, and beyond the merely-evident. Friends are necessary, but at bottom, the ultimate healing and humanizing encounter can only happen between the deaf man and Christ.

In each of our lives there is deafness and "muteness" or inarticulateness. So many things are unheard by us, fail to touch or resonate in our hearts. So many things call forth embittered and cynical reactions which wound and isolate when what is needed is a response of genuine compassion and welcoming. Similarly, so many things render us speechless or relatively inarticulate as we hold ourselves apart and defended: bereavement, illness, ignorance, personal woundedness, etc. As a result we live our commitments half-heartedly, our loves guardedly, our joys tentatively, our pains self-consciously and noisily --- but helplessly and without meaning in ways which do not edify --- and in all these ways therefore, we are less human, less articulate, less the obedient or responsive language event we are called to be. To each of us, then, and in whatever way or degree we need, Jesus says, "EPHPHATHA!" "Be thou opened!" He sighs in compassion and desire, unites himself with his Father in the power of the Holy Spirit, and touches us with his own hands and spittle.

May we each allow ourselves to be brought to Jesus for healing. May we be broken open and rendered responsive and transparent by his powerful Word of command and authority. Especially, may we each become the clear gospel-founded words of joy and hope in a world marked extensively and profoundly by deafness and the helplessness and the despair of noisy inarticulateness.

09 September 2018

Healing of the Deaf, Speech-Impaired Man (Reprise)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:00 PM

![]()

![]()

05 September 2018

What Would You Have Done IF. . .?????

[[Dear Sister, thank you for your post on the work you undertook 2 years ago or so. I wondered what you would have done had you discerned eremitical solitude was not something you were still called to? Probably that is difficult to answer but was this something you thought about?]]

[[Dear Sister, thank you for your post on the work you undertook 2 years ago or so. I wondered what you would have done had you discerned eremitical solitude was not something you were still called to? Probably that is difficult to answer but was this something you thought about?]]

Great question! And yes, it is certainly a difficult one to answer because I would only be considering what might have been. What I did think about was not so much what would change as what would remain the same. After all, certain truths, certain personal gifts, skills, inclinations, and obligations would remain whether I remained a hermit or not. I would still be a theologian, still be pastoral assistant at my parish; I would still be involved in the lives of clients as spiritual director, still be committed to writing about c 603, c 604 (perhaps), still be a writer and musician, and so forth. If I were ever to leave my vows/eremitical life, I would no longer be publicly vowed but I would remain bound by the evangelical counsels probably by private vows. My commitment to a life of prayer, to the work I have undertaken with the assistance of my director would remain -- and substantial parts of these would remain entirely unchanged.

However, some things might change, especially in terms of ministry. For instance, I would like to do more pastoral ministry in my parish --- though my not doing so is not solely a matter of being constrained by eremitical solitude. Still, this would be the first thing I would consider. Something that could dovetail with this is teaching. Again, to some degree I am allowed to do this even as a hermit but to a much more limited degree than I would if I left eremitical life. Unfortunately, there are other significant constraints on my life --- chronic illness with a medically and surgically intractable seizure disorder and chronic pain (complex regional pain syndrome) --- and these would still need to be dealt with as they are today. I have no doubt, however, that folks would help me in negotiating a wider world in terms of new or expanded work if that were to open up to me. It would be a learning situation for sure but what I know is, whatever I determined to undertake, I would not be doing it alone any more than I live eremitical life entirely alone.

So, my basic answer is my life would look a lot like it does today; it would involve the same gifts and activities with some broadening and expansion of things I have done (or considered doing) in the past. One thing I would definitely be doing, however, if I ceased to be a hermit, is spending more time with friends --- and whether I did these things with them or alone I would be seeing more movies, going to more museums, lectures, and concerts, and just getting out and about more (maybe on my new electric bike (!!!) but also on our local/regional transit system).

A note on the picture above: during our first year of work together, as part of a response to that same work I recovered some "lost gifts" and means of expression. One of these was drawing. Thus, I drew a picture of myself coloring/drawing because I saw myself (through the grace of God) slowly creating an entire universe "page by page" (not to mention tapping into the deepest places within myself in the process). It was a picture in which the individual pages often looked little different from one another and which took shape bit by bit; it was huger than I could ever capture on paper of course, but so we continued, step by step.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:21 PM

![]()

![]()

Does God Send or Choose Suffering for Us?

[[Dear Sister Laurel, do you believe God chose for you to experience the trauma you wrote about yesterday? Some people affirm that God chooses the pain they experience or the difficulties they have. I understand how that seems to make sense of things for them but for me it makes God something of a sadist. Maybe that's a bit strong but I think you know what I mean. Anyhow, do you think God chose the trauma you referred to so that you would become a hermit?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, do you believe God chose for you to experience the trauma you wrote about yesterday? Some people affirm that God chooses the pain they experience or the difficulties they have. I understand how that seems to make sense of things for them but for me it makes God something of a sadist. Maybe that's a bit strong but I think you know what I mean. Anyhow, do you think God chose the trauma you referred to so that you would become a hermit?]]

I have answered questions similar to this before, not about the trauma I referred to yesterday, but in general and perhaps in reference to the chronic illness/pain I deal with daily. You might look at, On Bearing the Crosses That Come Our Way. Other posts on the Theology of the Cross during the same time frame (@Aug. 2008) may also address this topic. My position on this has not changed but your questions take this position in a somewhat different direction than I may have taken in the past.

First, my foundational credo on suffering: I believe that God willed me and wills each of us to know God's love in whatever situation in which we find ourselves. I believe profoundly that God never abandons us --- even when others do. I believe that to whatever extent suffering is part of our lives because of the brokenness and distortion of our world (because most forms of suffering** are the result of the sin or estrangement from God which afflicts our world), our God will be there offering (his) comfort, encouragement, and empowerment --- even when we do not recognize the nature or the source of these things as we find ways to continue to live our lives and be our truest selves. I do not believe that God wills suffering, sends suffering, or somehow manipulates our lives and responses with suffering so that we might answer this vocation or that one. As I affirmed in the post linked above, God does not send us the crosses that come our way, but he does send us into a world full of them so that, through (his) grace, we may redeem them, and he certainly commissions us to carry those that come our way.

When I look at my own life I recognize that some of the pivotal circumstances of that life along with the life/love of God that dwelt and dwells at the core of my being together gradually created the heart of a hermit. But as I also noted, I could have lived that truth as a religious doing theology in the academy, working in a hospital chaplaincy program or in full time spiritual direction, as well as in a hermitage. I don't believe God created me to be a hermit, but I do believe God created me to be the fullest version of myself I could possibly be, that (he) continually worked to shape my heart, and when it began to look like a hermitage might be a place living my truth could happen, the shaping God had done helped me to perceive the promise of this way of life despite my own prejudices against it. (He) helped me listen to my heart, to the profound questions and yearning that resided there and to appreciate the way eremitical life might answer these beyond ordinary imagining. On the other hand, had I not discovered the possibilities or even the contemporary existence and meaningfulness of this vocation, I am certain God's shaping of my heart and movement within it would have empowered my recognizing and embracing another way to live the truth of who I am.

Whatever sense we make of suffering it is important that we do not truncate a theology of human freedom or a theology of Divine goodness and mercy in the process. I don't think your use of the term sadist is necessarily too strong in reference to a God who sends suffering or makes us suffer. Manipulative might be a better fit in some cases, but in either instance, the willing or sending of suffering is unworthy of the God of Jesus Christ who is Love-in-Act. Always God calls us to the fullness of human existence. What God ALWAYS wills is human life in abundance. When suffering comes our way God will accompany us and love us in a way which can prevent suffering from being ultimately destructive ("all things work for the good in those who love God," Romans 8:28), but this is far far different from sending or willing suffering.

I hope this is helpful.

** N.B., There are four forms of suffering that are "natural" or "existential"; that is, they belong to the human condition itself without reference to sin. Douglas John Hall outlines them in his book, God and Human Suffering. These are loneliness, anxiety, temptation, and limits. Loneliness underlies our hunger for love or the completion that comes to us in the other; it points to the dialogical nature of our very being. Anxiety is part of our need for security, peace, and the ultimate comfort of and communion with God. Temptation allows us to grow and mature in expressing our human dignity, to develop into persons of character, while limits are part of our drive for and achievement of transcendence; limits open us to surprise, to dreaming, to wonder and joy. There are also pathological and sinful versions of these forms of suffering but Hall is not speaking of these here.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:43 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: suffering -existential forms, suffering- natural forms, sufferings of Christ

On Inner Work and the Importance of Having Healing Well in Hand Prior to Profession

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I wondered about the inner work you refer to having undertaken during the past 2+ years. . . . Does every hermit do this kind of thing? Did you need to do this because of difficulties you were having with your vocation? . . . I don't mean to pry but if a person needs to undertake this kind of work should their diocese profess them? . . . Please, I really don't mean to offend but you also write that candidates for profession to your life should have their healing pretty much in hand before profession. Do you still believe that?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I wondered about the inner work you refer to having undertaken during the past 2+ years. . . . Does every hermit do this kind of thing? Did you need to do this because of difficulties you were having with your vocation? . . . I don't mean to pry but if a person needs to undertake this kind of work should their diocese profess them? . . . Please, I really don't mean to offend but you also write that candidates for profession to your life should have their healing pretty much in hand before profession. Do you still believe that?]]

Thanks for your questions. I understand where you are coming from and take no offense so please don't be concerned. First, I continue to believe that candidates for profession under canon 603 should have their own personal healing well in hand before approaching a diocese to petition for admission to profession and consecration. One must be relatively whole if one is to adequately discern or to commit to such a call --- perhaps even more than one needs to be in other more usual life contexts and commitments. Secondly, the inner work I have referred to over the past couple of years can be beneficial to anyone seeking to grow more fully into the persons they are called to be but who, over the years of their lives have been wounded in ways which may prevent a full, even exhaustive, response to God's call and presence. I don't know anyone who has not experienced some, even some very significant trauma or situations which wound personally and can prevent or at least hamper this kind of openness and response or "obedience." In fact, the inner work I have been referring to is geared to assisting every person to respond to God's presence and achieve an integrity of personhood which otherwise might remain merely potential.

At the same time I undertook this work when it became clear that there was significant essentially unhealed trauma I had grown up with and which needed to be addressed. I did so understanding that there was some risk this work might actually lead to the conclusion I was not really called by God to this vocation, but also, on the other hand, I appreciated that it was this very eremitical vocation that provided the time, motivation, and resources to do this work; more importantly, I think, it provided the personal, moral, and even the legal (canonical) obligation to do so as one publicly vowed to obedience and desiring to live the depth of the silence of solitude as well as "the privilege of love" identified as the core of Camaldolese life. Paradoxically then, I realized I was willing to risk discovering this was not my vocation precisely because I was in touch with the profound call of this vocation to personal wholeness and integrity. And over the past couple of years through this work I have only been confirmed in my conviction that it is in the silence of solitude that God calls me to an abundance of life I could not have imagined. So, while this work does not radically change my position on hermits having personal healing well in hand before petitioning for admission to profession and consecration it does nuance my position.

At the same time I undertook this work when it became clear that there was significant essentially unhealed trauma I had grown up with and which needed to be addressed. I did so understanding that there was some risk this work might actually lead to the conclusion I was not really called by God to this vocation, but also, on the other hand, I appreciated that it was this very eremitical vocation that provided the time, motivation, and resources to do this work; more importantly, I think, it provided the personal, moral, and even the legal (canonical) obligation to do so as one publicly vowed to obedience and desiring to live the depth of the silence of solitude as well as "the privilege of love" identified as the core of Camaldolese life. Paradoxically then, I realized I was willing to risk discovering this was not my vocation precisely because I was in touch with the profound call of this vocation to personal wholeness and integrity. And over the past couple of years through this work I have only been confirmed in my conviction that it is in the silence of solitude that God calls me to an abundance of life I could not have imagined. So, while this work does not radically change my position on hermits having personal healing well in hand before petitioning for admission to profession and consecration it does nuance my position.

One of the truths hermits sometimes recognize in rare cases is that they have been made ready for embracing a vocation to the silence of solitude for a very long time. This is not merely a matter of temperament but of formation by the combination of life circumstances and the grace of God. I came to see clearly that God accompanied me throughout my life, that (he) helped me understand and, in fact, be very sensitive to the difference between isolation and solitude from the time I was very small, that (he) gifted me in profound ways that actually suited me to a life of eremitical solitude as much as these gifts might have suited me to a life of apostolic activity in the academy or elsewhere. Tom Merton once wrote (perhaps tongue in cheek) that "hermits are made by difficult mothers"; Carl Jung once wrote that sometimes extraordinary and difficult circumstances can lead to a maturity which is surprising in someone who is so young. Analogously, extraordinary circumstances can suit one to eremitical life --- though it has to be emphasized these can also wound the person in ways which make her incapable of responding to such a call or even be unsuited to it. Since the externals of either case (i.e., life in solitude) can look similar or even identical it requires careful discernment --- and the assistance of those with experience in formation, etc., to determine the true character of the vocation with which one is dealing.

One of the truths hermits sometimes recognize in rare cases is that they have been made ready for embracing a vocation to the silence of solitude for a very long time. This is not merely a matter of temperament but of formation by the combination of life circumstances and the grace of God. I came to see clearly that God accompanied me throughout my life, that (he) helped me understand and, in fact, be very sensitive to the difference between isolation and solitude from the time I was very small, that (he) gifted me in profound ways that actually suited me to a life of eremitical solitude as much as these gifts might have suited me to a life of apostolic activity in the academy or elsewhere. Tom Merton once wrote (perhaps tongue in cheek) that "hermits are made by difficult mothers"; Carl Jung once wrote that sometimes extraordinary and difficult circumstances can lead to a maturity which is surprising in someone who is so young. Analogously, extraordinary circumstances can suit one to eremitical life --- though it has to be emphasized these can also wound the person in ways which make her incapable of responding to such a call or even be unsuited to it. Since the externals of either case (i.e., life in solitude) can look similar or even identical it requires careful discernment --- and the assistance of those with experience in formation, etc., to determine the true character of the vocation with which one is dealing.

The discernment needed in such cases is clearly significant, personally demanding --- and very rewarding. What absolutely must be evident to those involved in this process if they are to determine the hermit really is called by God to this vocation is that the person is genuinely embracing a call to human wholeness, has experienced the redemptive love of God in eremitical solitude in a significant way, and are compelled by personal integrity and faith to follow the work to its conclusion. I have noted this before here, but now I can be clear about the source of my conviction. With eremitical life specifically, coming to human wholeness involves a call to do this in "the silence of solitude". If one cannot do this or if one's growing wholeness and holiness makes one less able to remain peacefully in their hermitage, then one may need to leave eremitical life. If, however, this environment of eremitical solitude is clearly redemptive and the healing or sanctification one experiences as a hermit lead even more profoundly into the life of the hermitage, one's vocation will be confirmed.

But what if one is not (or is no longer) called to eremitical life? I believe that if one is not suited to eremitical solitude, living in this way will not have the same salvific character. Further, one may be unlikely to see the work required for healing to be a matter one must personally embrace because it is morally required by this vocation and one may therefore eschew it. In such cases, one will also have to submerge or even deny parts of themselves which are absolutely essential for personal wholeness and a life of responsive or obedient love.

But what if one is not (or is no longer) called to eremitical life? I believe that if one is not suited to eremitical solitude, living in this way will not have the same salvific character. Further, one may be unlikely to see the work required for healing to be a matter one must personally embrace because it is morally required by this vocation and one may therefore eschew it. In such cases, one will also have to submerge or even deny parts of themselves which are absolutely essential for personal wholeness and a life of responsive or obedient love.

More, as one undertakes the work required and experiences the healing it can effect in and of itself (that is, no matter the context), one is increasingly unlikely to be able to return to a physical solitude that may have been more mute isolation or escapism than what canon 603 describes as or allows to be called the silence of solitude. Eremitical life would simply not (or no longer) be healthy for one or what one could tolerate. Growing wholeness and fullness of life developing from the work undertaken will lead one to be increasingly unable to embrace the constraints of eremitical life. A more positive way of saying this is to note it will not represent the realm of freedom one really needs to be fully themselves, fully human. One will certainly not be able to truly know eremitism as a gift of God with which God gifts one either for one's own abundant life or for the sake of the Church and world.

Regarding your first questions, every responsible hermit works regularly with a spiritual director and beyond this, I have to trust that every publicly professed hermit will undertake the work or therapy or whatever it takes to fully respond to the vocation with which they have been entrusted once it becomes clear such work is called for. Certainly canonical hermits, hermits who have thus accepted the obligations and rights associated with eremitical life lived in the name of the Church, will generally be unable to eschew the necessary personal and inner work needed to embrace the life God summons them to within the hermitage or as someone with an ecclesial vocation. As I have noted before, I have been very fortunate in having a director who is specially trained in PRH and who was able to offer me the unique accompaniment needed to work through significant unhealed trauma even as she was able to keep her finger on the pulse of my vocation and assist in my ongoing formation. I do believe, however, that if one knows this kind of work is needed she should undertake it before admission to profession; it is entirely imprudent to forego it because of the effect healing has on the whole person.

While your question about this is a good and logical or understandable one, I was not having difficulties with my vocation. In truth, it was the fact that I was doing well in it which, at least in part, led me to realize the need for this work and gave me the courage to undertake it, risky though it might be to that same vocation. As hermits find in the silence of solitude, one must face oneself squarely in light of the love of God. A solitary life of prayer will uncover more and more any need for healing or forgiveness.

While your question about this is a good and logical or understandable one, I was not having difficulties with my vocation. In truth, it was the fact that I was doing well in it which, at least in part, led me to realize the need for this work and gave me the courage to undertake it, risky though it might be to that same vocation. As hermits find in the silence of solitude, one must face oneself squarely in light of the love of God. A solitary life of prayer will uncover more and more any need for healing or forgiveness.

As my director and I continue the work and deep healing God wills for me, and as I come to know and embrace my whole self even more completely in light of this work, I have experienced an even greater sense of eremitical call specifically as a diocesan hermit embedded in a parish community; with this my excitement regarding canon 603 and its implementation in the Church has grown significantly. I wish I had undertaken this work before profession (or at least known clearly it was still needed) as is prudent and ordinarily necessary, but I am grateful to God my very vocation made it possible as well as necessary that I undertake it now and that it in turn has led to the reaffirmation of an ecclesial call to the silence of solitude.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:53 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Canon 603, discernment of eremitical vocations, inner work, PRH, the Silence of Solitude

03 September 2018

On Birthdays and Anniversaries: Looking Back in order to Look Ahead

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:51 AM

![]()

![]()

02 September 2018

On Law as Unnecessarily Burdensome for the Hermit Life

Dear Sister, when hermits write about the law being a burden imposed on them by others and imposed in a way which prevents them from living eremitical life in simplicity and freedom what are they talking about? I am thinking about the following passages and others from the same post, [[People who augment laws and make them into millstones of detrimental outcome surely do so without realizing they themselves are causing the interference with spiritual progression and the freedom to follow Jesus in truth, beauty, and goodness.]] or [[The laws become so important to them, yet they increasingly are hindered by their own interpretation of laws in attempts to justify their positions and superiority they may claim as a result of the overly or misinterpreted laws. This can lead to their in essence interfering (or being tempted to interfere) with the simplicity and freedom that Jesus desires for others to follow Him in the truth, beauty, and goodness of the mystery of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.]] Does Canon 603 function in this way as a burden imposed without need and leading to a "detrimental outcome"? Do you think your own writing about the canon functions this way for some? Why would someone think this?]]

Dear Sister, when hermits write about the law being a burden imposed on them by others and imposed in a way which prevents them from living eremitical life in simplicity and freedom what are they talking about? I am thinking about the following passages and others from the same post, [[People who augment laws and make them into millstones of detrimental outcome surely do so without realizing they themselves are causing the interference with spiritual progression and the freedom to follow Jesus in truth, beauty, and goodness.]] or [[The laws become so important to them, yet they increasingly are hindered by their own interpretation of laws in attempts to justify their positions and superiority they may claim as a result of the overly or misinterpreted laws. This can lead to their in essence interfering (or being tempted to interfere) with the simplicity and freedom that Jesus desires for others to follow Him in the truth, beauty, and goodness of the mystery of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.]] Does Canon 603 function in this way as a burden imposed without need and leading to a "detrimental outcome"? Do you think your own writing about the canon functions this way for some? Why would someone think this?]]

Thanks for your questions. I couldn't locate the source of this citation to check out the context (not your fault of course!) but I wish I understood what is really being argued in such passages as the ones you quote. I can understand one source of your own questions. After all, the comments are so vague and overly general that it is simply difficult to understand whether they are cogent and for whom, in what way, or to what extent. Does every person interpreting or explaining a law or canon fall under this condemnation or is the person speaking of someone in particular? If someone's explanation of the law or canon means that some will discover they have misunderstood and misapplied either the law/canon or some of its central terms, does this mean the one doing the explaining has interfered with the others' freedom? If technical terms are explained in such a process so that some find they had a mistaken sense of what was really being said, is the one explaining the proper usage then guilty of interfering with the person's discipleship of Jesus? Since you say the person writing this is a hermit I can suppose s/he is speaking of c 603 and those who write about it, but unless s/he is speaking of somehow "making things difficult" for those already professed under this canon his/her comments make little sense. Here's why.

Thanks for your questions. I couldn't locate the source of this citation to check out the context (not your fault of course!) but I wish I understood what is really being argued in such passages as the ones you quote. I can understand one source of your own questions. After all, the comments are so vague and overly general that it is simply difficult to understand whether they are cogent and for whom, in what way, or to what extent. Does every person interpreting or explaining a law or canon fall under this condemnation or is the person speaking of someone in particular? If someone's explanation of the law or canon means that some will discover they have misunderstood and misapplied either the law/canon or some of its central terms, does this mean the one doing the explaining has interfered with the others' freedom? If technical terms are explained in such a process so that some find they had a mistaken sense of what was really being said, is the one explaining the proper usage then guilty of interfering with the person's discipleship of Jesus? Since you say the person writing this is a hermit I can suppose s/he is speaking of c 603 and those who write about it, but unless s/he is speaking of somehow "making things difficult" for those already professed under this canon his/her comments make little sense. Here's why.

Canon 603 applies in a legally and morally binding way only to those who have freely chosen and been chosen to be professed under it. It applies only when this person and her diocese have engaged in a serious process of mutual discernment and agreed to move forward with the profession and (in the case of perpetual vows) the consecration in the Bishop's hands under this canon. The canon is well-understood by all involved and canonists are available to explain the exigencies to both the hermit and her Bishop before any legal commitments are made. (They will also listen to the hermit who demonstrates on the basis of her own experience how terms in the canon should be nuanced and understood! The vocation is mutually discerned and in some ways, explored. The parties involved listen to one another to discern the will of God.)

NO SOLITARY HERMIT who did not experience canon 603 creating an extraordinary realm of freedom in which one can live the eremitical vocation or who felt that canon 603 functioned as a millstone preventing her from living her vocation in freedom and simplicity would ever seek or be admitted to such profession; moreover, if this situation was discovered after admission to first vows for instance, she would never seek or be allowed to be admitted to further profession or to consecration. If the Church changed the terms of the canon and a hermit found this burdensome in the way described, then such a hermit might need to pursue dispensation. Nor is this a problem since one does not need to be professed canonically to be a hermit within the Church. If one wishes to represent eremitical life in the name of the Church, if one wishes to serve the Church in this way and feels called by God to do so, then I wonder how the Church's own norm governing such a life could be considered unnecessarily burdensome.

As has been noted here a number of times canon 603 defines one particular eremitical vocation. There are other ways to live eremitical life so if canon 603 served to truly curtail one's freedom (not merely one's many liberties!) or seemed to complicate one's life in detrimental ways, it seems pretty clear that for such a person, this is not the avenue they should use to pursue living eremitical life. In other words they are not called to this specific vocation or to the specific rights and obligations associated with it and need not be troubled by the canon nor by those who comment on or interpret it. For that matter if the person commenting on or interpreting c 603 knows nothing about the canon or really seems to be speaking or writing in ways detrimental to the vocation itself and to hermits canonically professed under it, then again, why would anyone listen to them longer than it takes to check out their findings with other hermits and professional canonists who are recognized for being knowledgeable in regard to this canon?

As has been noted here a number of times canon 603 defines one particular eremitical vocation. There are other ways to live eremitical life so if canon 603 served to truly curtail one's freedom (not merely one's many liberties!) or seemed to complicate one's life in detrimental ways, it seems pretty clear that for such a person, this is not the avenue they should use to pursue living eremitical life. In other words they are not called to this specific vocation or to the specific rights and obligations associated with it and need not be troubled by the canon nor by those who comment on or interpret it. For that matter if the person commenting on or interpreting c 603 knows nothing about the canon or really seems to be speaking or writing in ways detrimental to the vocation itself and to hermits canonically professed under it, then again, why would anyone listen to them longer than it takes to check out their findings with other hermits and professional canonists who are recognized for being knowledgeable in regard to this canon?

I know that some have been upset to find 1) that they cannot live as a consecrated solitary hermit except under canon 603, or sometimes 2) that their dioceses refused them admission to profession under canon 603 (never an easy decision for the one being refused admission to profession!), or even 3) that their private vows do not initiate into the consecrated state but leaves them in the stable state of life they already found themselves in (whether lay or ordained). Others have been upset to find that c 603 was meant for solitary hermits (including those coming together for mutual support in a laura), and not for those seeking to form a community of "hermits" or as a way to be professed canonically so one can begin a religious institute. But in each of these cases those explaining these issues are merely explaining facts already known to the authors of the canon or the findings of expert commentators on the canon --- facts which need to be disseminated.

With different issues (e.g., what constitutes a laura, how does the silence of solitude differ from silence and solitude, what is the charism of the vocation, how important is spiritual direction or a diocesan delegate, what should formation look like and how long should it take, the place of temporary profession, the role of the Bishop, etc) we are dealing with elements of the canon where the lived experience of hermits can be especially helpful --- more helpful sometimes than the input of canonists, bishops, et al who have not lived the canon. To write about these is not to create law or to add onerous requirements; it is, in fact, to write about ways of ensuring the life is lived with integrity in true freedom when the canon itself is unclear or silent on the matter, or when time frames and other things which are applicable to life in community and established in canon law just don't work for solitary eremitical life.

Bishops, of course can take such comments and opinions for what they are worth. If they have a strong candidate for profession under canon 603 they are apt to listen to that candidate if something suggested really doesn't work for them. Still, if suggestions seem prudent to dioceses professing hermits under canon 603 dioceses have the right and even some responsibility to adopt these. Canon 603 is an ecclesial vocation so it is up to more than the individual desiring profession to determine what most seems to serve both the Church's eremitical tradition and her contemporary witness to the Gospel.

Bishops, of course can take such comments and opinions for what they are worth. If they have a strong candidate for profession under canon 603 they are apt to listen to that candidate if something suggested really doesn't work for them. Still, if suggestions seem prudent to dioceses professing hermits under canon 603 dioceses have the right and even some responsibility to adopt these. Canon 603 is an ecclesial vocation so it is up to more than the individual desiring profession to determine what most seems to serve both the Church's eremitical tradition and her contemporary witness to the Gospel.

You ask about my writing. I am sure my own writing has served as a source of irritation and disappointment to some --- most especially those who mistakenly believed (or persist in the argument) that private vows are the normal way to become a consecrated hermit, or who treat can 603 as an entirely optional way to solitary consecrated eremitical life. I'm pretty sure my writing has been a source of difficulty for those who are looking to use c 603 as a stopgap way to become consecrated as a lone person but not as a solitary hermit. But many more have found my writing helpful in explaining terms which those without a background in religious life might misunderstand and in addressing abuses that many have encountered over time. Fortunately, even more have found some of my posts on the spirituality and charism of canon 603 especially helpful. Because what I have written about canon 603 is rooted in my own experience, research, and education, and because I seek to convey truth which is not directly available to those standing outside this vocation, I don't believe it can serve as a burden unless one is not called to this same vocation but is instead seeking to misuse the canon as a stopgap for inappropriate motives. Other solitary (c.603) hermits will (and do!) mainly verify the essential truth of what I have written on the basis of their own experience.

As I have said a number of times here canon 603 is a truly beautiful balance of non-negotiable elements and personal flexibility which produces a sacred "space" where one can pursue solitary eremitical life with God in authentic and ever-deepening freedom. It is a timely canon which allows for a contemporary vocation our world and various cultures are truly hungry for --- without understanding what that actually is. Exploring it has been and continues to be a joy for me because it has served as I believe the canon is supposed to serve in the life of the solitary consecrated hermit, viz, it has deepened my understanding of the life, of its importance, of how God is using my life circumstances to witness to the Gospel and why that is significant for the Church and others. And of course it has served to structure and govern my life as it provides a stable context for focused growth as a solitary hermit in the Christian Tradition. This vocation is unquestionably a gift of the Holy Spirit and simply out of gratitude it deserves the best hermits', theologians', and canonists' experience, talents, and training or education can give it --- my own included.

As I have said a number of times here canon 603 is a truly beautiful balance of non-negotiable elements and personal flexibility which produces a sacred "space" where one can pursue solitary eremitical life with God in authentic and ever-deepening freedom. It is a timely canon which allows for a contemporary vocation our world and various cultures are truly hungry for --- without understanding what that actually is. Exploring it has been and continues to be a joy for me because it has served as I believe the canon is supposed to serve in the life of the solitary consecrated hermit, viz, it has deepened my understanding of the life, of its importance, of how God is using my life circumstances to witness to the Gospel and why that is significant for the Church and others. And of course it has served to structure and govern my life as it provides a stable context for focused growth as a solitary hermit in the Christian Tradition. This vocation is unquestionably a gift of the Holy Spirit and simply out of gratitude it deserves the best hermits', theologians', and canonists' experience, talents, and training or education can give it --- my own included.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:32 AM

![]()

![]()

31 August 2018

In Memoriam Dom Robert Hale, OSB CAM

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:50 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Dom Robert Hale -- In Memoriam

29 August 2018

Update On Father Robert Hale, OSB Cam

Update on Fr. Robert (Wed. 8/29):

Fr. Robert took a sharp turn for the worse Wednesday morning. He has been taken off of all life support now and transitioned into hospice/comfort care. It may be hours, it may be days, but we are certainly at the end of this phase of the journey. Fr. Andrew and I are with him. Please pray for the safe passing of our brother and father into the Privilege of Love.

Cyprian

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:32 PM

![]()

![]()

Followup Question: Ancient and Contemporary Hermits, Ancient and Contemporary Asceticism

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

Thanks for your questions and your very good points. First, let me say I generally agree with you about the ancient hermits you refer to. That is especially true if we are talking about folks like the Desert Mothers and Fathers from @ the 3rd-4th Centuries, the original Carthusians, the Camaldolese, etc. All of these hermits lived eremitical lives of serious asceticism and poverty. The deserts they entered required they make do with what they had at hand and that they live their faith commitments in and through such circumstances. Today the Carthusians continue to live similar lives --- though ordinarily in established Charterhouses with the basic means for healthy lives given to God alone. While people reading the stories of these hermits today might not understand what motivated or motivates them, I think most would find the accounts of their lives and foundations to be powerful witnesses to being driven by something greater than ordinary life seems to provide. One may not understand what moved these hermits but I think most would admire their courage and persistence.

What moves me most when I read or read about these ancient and contemporary hermits is that the hardships they lived, the asceticism they undertook all fade into the background in light of the reasons they undertook these things and their accounts of what they found in their quests. Specifically, the circumstances in which they found themselves did not detract from their eremitical lives, nor were they the focus of these lives; they were a part of the soil in which these lives were fruitful. As a result these hermits (or those who author the accounts we have of their lives) write not primarily about the difficult, even miserable conditions in which they found themselves but about the God who held them securely in spite of these conditions and the struggles they required. More, they do so in ways which are coherent and compelling. In other words, they lived lives faithful to their sense of God's call; they prayed assiduously and worked and grew in their gratefulness to God. They assisted one another, were faithful to a call to solitude and, when a situation was truly unlivable or manifestly unhealthy, they moved on and lived their call elsewhere. So, while asceticism was essential and sometimes simply unavoidable anyway it was the eremitical or "desert life" itself in which one is fulfilled in God which was the focus of their efforts; it is this redemptive content that is the compelling and clear center of their witness --- their living, writing, apothegms, and the accounts of those who write about these hermits.

What moves me most when I read or read about these ancient and contemporary hermits is that the hardships they lived, the asceticism they undertook all fade into the background in light of the reasons they undertook these things and their accounts of what they found in their quests. Specifically, the circumstances in which they found themselves did not detract from their eremitical lives, nor were they the focus of these lives; they were a part of the soil in which these lives were fruitful. As a result these hermits (or those who author the accounts we have of their lives) write not primarily about the difficult, even miserable conditions in which they found themselves but about the God who held them securely in spite of these conditions and the struggles they required. More, they do so in ways which are coherent and compelling. In other words, they lived lives faithful to their sense of God's call; they prayed assiduously and worked and grew in their gratefulness to God. They assisted one another, were faithful to a call to solitude and, when a situation was truly unlivable or manifestly unhealthy, they moved on and lived their call elsewhere. So, while asceticism was essential and sometimes simply unavoidable anyway it was the eremitical or "desert life" itself in which one is fulfilled in God which was the focus of their efforts; it is this redemptive content that is the compelling and clear center of their witness --- their living, writing, apothegms, and the accounts of those who write about these hermits.

The questions I had been asked earlier focused on the role of the diocese in allowing a diocesan (solitary consecrated Catholic) hermit to live in uninhabitable, and even harmful situations or circumstances. What I tried to stress was that a diocese will allow a hermit she has publicly professed to purchase and remodel a house in order to have a hermitage, but that it cannot become a fulltime project which detracts from the hermit's ability to live her Rule or to live a fully and abundantly human life --- especially in the long term. Dioceses can and do allow hermits to build hermitages but they also require prudence in the details. This is only appropriate. Remember that dioceses have to discern the nature and quality of the vocation in front of them; beyond this they must supervise, protect, and nurture such vocations. If an individual is going into substantial debt, living a more and more isolated life, and injuring themselves or exacerbating existing conditions and illnesses needlessly all in the name of creating this "hermitage" then something has gotten skewed, namely, the living of a healthy eremitical life itself has lost its priority and been replaced by concern for one's hermitage itself.

A hermit can make a hermitage of almost any habitable dwelling place. I am thinking now of a chapter written by a Trappist hermit at the Abbey of Gethsemani in KY. (Paul Quenon, OCSO, In Praise of the Useless Life, A Monk's Memoir) In this section devoted to the "Our Golden Age of Hermits" at the Abbey, the author describes the great variety of hermitages found on the Abbey grounds in the years following Thomas Merton's death. Besides Merton's own cinderblock hermitage, hermitages were built in a variety of places out of a variety of materials. Fr. Flavian's was built of cedarwood and was small and isolated but with large small-paned windows taking up most of a couple of walls; Dom James' hermitage (which was designed and built for him after his years of service as Abbot by one of the brothers) was constructed with three wings constructed of steel and glass and cantilevered from a concrete base. The base contained the kitchen, bedroom, and bath, while one wing was the chapel, another a porch and entrance, and a third a living room. As one approached the hermitage from the Abbey all one could see was a pyramid of stone with a slot for a window. (Dom James retired to this hermitage that was a 30 minute drive from the main abbey buildings. He was notably frugal in terms of heating and other expenses, including food; later he was assaulted by intruders and moved back to the abbey infirmary where he would be safe from additional harm.).

A hermit can make a hermitage of almost any habitable dwelling place. I am thinking now of a chapter written by a Trappist hermit at the Abbey of Gethsemani in KY. (Paul Quenon, OCSO, In Praise of the Useless Life, A Monk's Memoir) In this section devoted to the "Our Golden Age of Hermits" at the Abbey, the author describes the great variety of hermitages found on the Abbey grounds in the years following Thomas Merton's death. Besides Merton's own cinderblock hermitage, hermitages were built in a variety of places out of a variety of materials. Fr. Flavian's was built of cedarwood and was small and isolated but with large small-paned windows taking up most of a couple of walls; Dom James' hermitage (which was designed and built for him after his years of service as Abbot by one of the brothers) was constructed with three wings constructed of steel and glass and cantilevered from a concrete base. The base contained the kitchen, bedroom, and bath, while one wing was the chapel, another a porch and entrance, and a third a living room. As one approached the hermitage from the Abbey all one could see was a pyramid of stone with a slot for a window. (Dom James retired to this hermitage that was a 30 minute drive from the main abbey buildings. He was notably frugal in terms of heating and other expenses, including food; later he was assaulted by intruders and moved back to the abbey infirmary where he would be safe from additional harm.).

Br Odilo built a hermitage from scraps from other projects; some monks lived in trailers, one in an old "pig house"; Brother Rene's 16'X8' hermitage was made from the scraps of wood left over after the abbey monks made cheese boxes and it was roofed with corrugated metal; it had neither electricity nor running water but it provided the place where Br Rene could pray and rest in solitude as his own life required. His regular physical needs were taken care of in the abbey itself so the extreme poverty of the hermitage was not problematical in this way. I am also reminded of a contemporary Camaldolese who, in setting up a solitary hermitage, decided to convert a utility shed of the type used today for tools, etc. He rents living space from another person, but the shed is his hermitage and allows him time and space in privacy and solitude; it is snug and comfortable for this use, but it is not habitable and he will spend no time making it so.

Folks hearing the story of any of these hermits would rightly wonder if that story focused on the details of the hermitage, the struggle to build it, the terrible expense and injuries incurred in its building, the hermit's exacerbated chronic pain and illness occasioned by the conditions of his solitude. The point, of course, is that the hermitage itself was of less concern than the call to the silence of solitude and the life of solitary prayer. People find or build a place they can live such a life, but they do not give over years of their lives building the hermitage at the expense of their health or the life they are committed to live in the process. A diocesan hermit's diocese/bishop would never allow this, nor should they I think.

Simplicity? Sacrifice? Asceticism? Frugality? Yes, of course. But these will necessarily involve limitations on the time and energy spent on the hermitage itself. If versions of these are embraced in a way which detracts from one's ability to live the very life they are committed to living, no diocese would or should permit it. Similarly, I also think it is prudent of dioceses to insist that diocesan hermits have a reliable way to support themselves. Dioceses may (but are not required to) assist in times of emergency and temporary need but it is important that the hermit be responsible for her own support and legal decisions --- not least so dioceses are not to be left liable for expenses, injuries, etc., when something untoward happens.

Simplicity? Sacrifice? Asceticism? Frugality? Yes, of course. But these will necessarily involve limitations on the time and energy spent on the hermitage itself. If versions of these are embraced in a way which detracts from one's ability to live the very life they are committed to living, no diocese would or should permit it. Similarly, I also think it is prudent of dioceses to insist that diocesan hermits have a reliable way to support themselves. Dioceses may (but are not required to) assist in times of emergency and temporary need but it is important that the hermit be responsible for her own support and legal decisions --- not least so dioceses are not to be left liable for expenses, injuries, etc., when something untoward happens.

Again, this is all about living and protecting a vocation which is a gift of God. Not all historical forms of asceticism have been edifying, nor have all forms of suffering or isolation. It seems to me that we are more sensitive today to what are healthy forms of these, or what are forms which speak primarily of redemption rather than of sin/brokenness; it also seems to me that the Church, in approving certain eremitical vocations and disapproving others demonstrates this sensitivity and insists that canonical or public eremitical vocations witness to the redemption that comes to each of us through and in Christ. I hope this is of assistance to you.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:10 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: asceticism, Canon 603 - false solitude

28 August 2018

Parable of the Ten Virgins (Reprise)

Parables have a unique capacity to take us where we are and lead us to Christ. It doesn't matter that we are all in different places. We enter the story and thus enter a sacred space where we can meet God in Christ ourselves. For this reason, although I have written about this parable before, it had a freshness for me this week. Themes may remain similar (waiting, covenant, consummation of a wedding, faithfulness, preparation, celebration, future fulfillment, foolishness, wisdom, etc) but what the parable calls for today will differ from what it personally entailed for the hearer yesterday. It seems to me this parable describes and calls us each to a life of prayer, a life given over to another so that his own purposes may be fulfilled through our relationship. It is the story of a life given over to waiting; it is a waiting of disciplined preparation and attention, but it is also, for that very reason, waiting which is joyful and full of promise and hope. It is the kind of waiting which signals a life where, in terms of today's parable, one especially prepares oneself to be surprised by the Bridegroom's promised and inevitable coming and by all he has done to prepare for us as his bride.

Reminder: The Nature of Jewish Marriages in Jesus' Day

Jewish weddings took place in two stages. First came the betrothal in which the two were joined in a covenant of marriage. This was more than an engagement and if it was to be sundered it could only occur through processes called "divorce". After the betrothal the bridegroom went to his family home and began to prepare for his bride. He ordinarily began building an addition to the family home. It was understood that he would provide better accommodations than his bride had had until this point. (We should all be thinking of this situation when we hear Jesus say, "I go to my Father's house to prepare a place for you.) Meanwhile the bride also begins a period of preparation. There is sewing to do and lessons in being a wife. There is preparation for the day her bridegroom will come again to take her to his home where the two shall become one (in ritual marriage) and where the marriage will be consummated.

At the end of about a year (the groom's Father makes sure his Son does not do a haphazard job on the new addition just so he can get to his bride sooner!), on a day and at an hour the bride does not know, the groom comes with his friends. They bear torches, blow the shofar, and announce, "The Bridegroom comes" --- just as we hear in Friday's Gospel. The bride's attendants come forth with their own lamps and, with the entire town, accompany her to her new home. The marriage of this bride and groom symbolizes (in the strongest sense of that term) the marriage of God to his people achieved on Sinai. Thus, the service the bridesmaids and groomsmen do for these friends is also a service they do for Israel and a witness to God's ineffable mercy and covenant faithfulness.

At the end of about a year (the groom's Father makes sure his Son does not do a haphazard job on the new addition just so he can get to his bride sooner!), on a day and at an hour the bride does not know, the groom comes with his friends. They bear torches, blow the shofar, and announce, "The Bridegroom comes" --- just as we hear in Friday's Gospel. The bride's attendants come forth with their own lamps and, with the entire town, accompany her to her new home. The marriage of this bride and groom symbolizes (in the strongest sense of that term) the marriage of God to his people achieved on Sinai. Thus, the service the bridesmaids and groomsmen do for these friends is also a service they do for Israel and a witness to God's ineffable mercy and covenant faithfulness.On Waiting and preparing to be Surprised: The Life of Prayer

We are each called to be spouses of Christ. Christ has gone to his Father's house to prepare a place for us and we are called to spend the time between our betrothal and the consummation of this marriage in joyful preparation and waiting for that day. In other words, everything we do and are is to be geared to that day. One response to this reality is to develop a prayer life and commit to a life of prayer. (I would argue we are all called to this but that a solid prayer life and even a life of prayer looks different depending on the context and our state of life. For instance, a life of prayer in a family looks differently than a life of prayer in a hermitage.) This parable describes very well for me the dynamics of a life of prayer. Simultaneously it describes the celebratory nature of genuine waiting because prayer implies both waiting for and waiting on.

We all know both kinds of waiting. Neither is always easy for us. We wait for our moment before the cashier in grocery stores lines and are unhappy we have to be there. We look at magazines in the nearby racks, shift restlessly from foot to foot, fall prey to impulse buys of small items located in front of us for precisely this reason, and get more irritable by the moment. (Waiting is hard because it means some form of incompleteness and lack of control; thus we impulse buy to get a sense of completion, control, etc.) We tell ourselves we have better things to do, that our time is important -- often more important, we judge, than that of the person standing in front of (or behind!) us. (There's the specter of entitlement and narcissism that so plagues our culture. The whole dynamic of waiting reminds us we are not the center of the universe and it is not easy to take sometimes.) We fill our time, our minds and our hearts with all kinds of things to distract us from waiting; at the same time we thus prevent ourselves from being open to the new and unexpected.

Similarly waiting on others is not always easy either. Wait staff in restaurants sometimes resent the very guests they are meant to serve; work keeps them from their "real lives". And some of these wait staff take it out on those they are meant to serve. Whether this means allowing some to go unserved while waiters talk on cell phones, or arguing with and blaming customers, or actually doctoring the dishes served at the table, putting nasty comments on the bill, etc. waiting on others can be challenging and demanding; our own inability to wait on God is an important reason we fail to pray as we are called to. We may fail at this out of ignorance; we may not know prayer is about putting ourselves at God's disposal rather than expecting God to be at ours. We may be unwilling or resistant to putting ourselves at God's disposal or to order our lives around this relationship as fully as we know we ought.

Similarly waiting on others is not always easy either. Wait staff in restaurants sometimes resent the very guests they are meant to serve; work keeps them from their "real lives". And some of these wait staff take it out on those they are meant to serve. Whether this means allowing some to go unserved while waiters talk on cell phones, or arguing with and blaming customers, or actually doctoring the dishes served at the table, putting nasty comments on the bill, etc. waiting on others can be challenging and demanding; our own inability to wait on God is an important reason we fail to pray as we are called to. We may fail at this out of ignorance; we may not know prayer is about putting ourselves at God's disposal rather than expecting God to be at ours. We may be unwilling or resistant to putting ourselves at God's disposal or to order our lives around this relationship as fully as we know we ought.Again, in prayer we both wait for and wait on God. We wait for God and allow him the space to love and touch us as he will. We wait in the sense of the bride, knowing both that she is betrothed and thus wed to her groom while recognizing and honoring as well that the consummation of this relationship (and the proleptic experiences we occasionally have while waiting) come to us inevitably but at moments when we do not expect them. The temptation of course is to do as we do in the Safeway checkout line: fill our time with unworthy activities, seek distractions which relieve the tension of waiting, allow entitlement and impulsivity to replace patience and perseverance. But when we do not succumb to temptation, in prayer we wait for God. We wait in the sense of those preparing for something greater which we cannot even imagine. In other words, we wait as persons of hope whose ultimate union with our beloved is already begun and remains promised and anticipated in everything we say and do. We wait to be surprised by the one we know will come. And when we do, everything and everyone entering our purview will fire us with anticipation, will look, at least for a moment as the one we are awaiting. Each one may be the bridegroom, or his messenger, or someone with word of him and his own preparations. Each one bears promise and becomes a symbol of our hope.

At the same time we wait for God in Christ, we wait on God. Our prayer is not merely a matter of seeking God, much less of asking God for favors --- though it will assuredly and rightly include pouring out our hearts to him. Still, we are called to leave behind the prayer that is self-centered and adopt that which is centered instead on God's own life and will. Mature prayer is first of all a matter of making ourselves available to serve God so that his own love may be fulfilled, God's own plans realized, the absolute future he summons all of creation to may culminate in him and the Reign of sovereignty he wills to share with us is perfected. Again, in prayer we prepare to be surprised by that which we already know most truly and desire most profoundly. As in the Transfiguration we prepare to be surprised by that which has been right in front of us all along.

In the life of prayer and discipleship both waiting for and waiting on God take commitment, diligence, and attentiveness. Both require patience and persistence. It is to this we are each and every one of us called. No one can do this for us. The fuel and flame of our hearts and prayer lives is something only we can tend, only we can steward this fire in patient and joyful preparation for our Bridegroom's coming. It is in this that the foolish virgins failed and the wise virgins succeeded. The question Jesus' parable poses to us is which will we ourselves be, wise or foolish?

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:43 PM

![]()

![]()

24 August 2018

Prayers Requested for Dom Robert Hale, OSB Cam

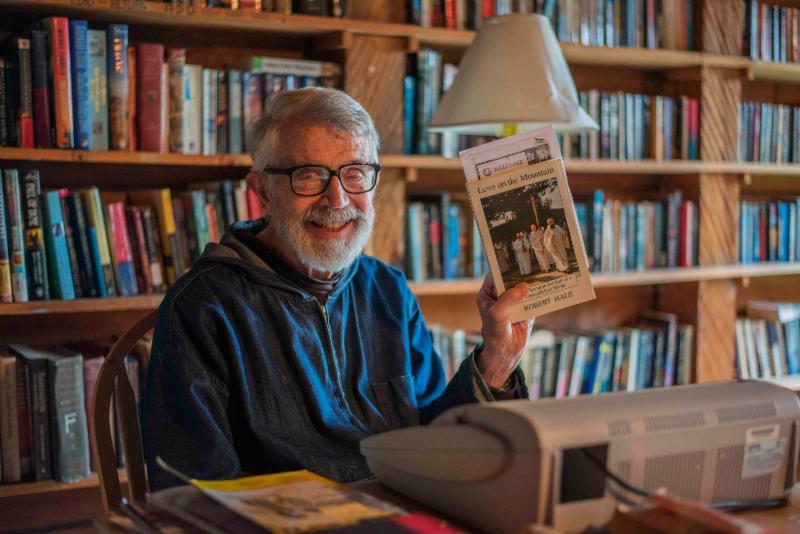

When I was first becoming a diocesan hermit Father Robert read my proposed Rule and gave me suggestions --- mainly an encouragement that I build in enough time for rest. For those who have not already done so I recommend reading Dom Robert's, Love on the Mountain, the Chronicle Journal of a Camaldolese Monk. Written while Robert was Prior it is a touching, often humorous autobiographical account of his community's life as Camaldolese in Big Sur. I have mentioned this before but do so again since I am rereading it as part of keeping Dom Robert in prayer.

When I was first becoming a diocesan hermit Father Robert read my proposed Rule and gave me suggestions --- mainly an encouragement that I build in enough time for rest. For those who have not already done so I recommend reading Dom Robert's, Love on the Mountain, the Chronicle Journal of a Camaldolese Monk. Written while Robert was Prior it is a touching, often humorous autobiographical account of his community's life as Camaldolese in Big Sur. I have mentioned this before but do so again since I am rereading it as part of keeping Dom Robert in prayer.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:58 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Dom Robert Hale, Love on the Mountain

22 August 2018

Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard (Reprise)

Today's Gospel is one of my all-time favorite parables, that of the laborers in the vineyard. The story is simple --- deceptively so in fact: workers come to work in the vineyard at various parts of the day all having contracted with the master of the vineyard to work for a day's wages. Some therefore work the whole day, some are brought in to work only half a day, and some are hired only when the master comes for them at the end of the day. When time comes to pay everyone what they are owed those who came in to work last are paid first and receive a full day's wages. Those who came in to work first expect to be paid more than these, but are disappointed and begin complaining when they are given the same wage as those paid first. The response of the master reminds them that he has paid them what they contracted for, nothing less, and then asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own money. A saying is added: [in the Kingdom of God] the first shall be last and the last first.

Today's Gospel is one of my all-time favorite parables, that of the laborers in the vineyard. The story is simple --- deceptively so in fact: workers come to work in the vineyard at various parts of the day all having contracted with the master of the vineyard to work for a day's wages. Some therefore work the whole day, some are brought in to work only half a day, and some are hired only when the master comes for them at the end of the day. When time comes to pay everyone what they are owed those who came in to work last are paid first and receive a full day's wages. Those who came in to work first expect to be paid more than these, but are disappointed and begin complaining when they are given the same wage as those paid first. The response of the master reminds them that he has paid them what they contracted for, nothing less, and then asks if they are envious that he is generous with his own money. A saying is added: [in the Kingdom of God] the first shall be last and the last first.