Your questions at first struck me as difficult to respond to. That is because I am doing those things you are questioning and I am sharing about it here. So, why wouldn't I believe that these are all possible? What I write here is rooted in my own experience and my own reflection on and analysis of that experience, even when I don't share the details of all of that. Not every hermit will write about this journey, or analyze and reflect on it in the same way, but every authentic hermit will make this inner journey with and into God, different as it may look from one of us to the next. I came to eremitical life with a theological background, what had grown to be an interest in "chronic illness as vocation", and a personal background that made the exploration of existential solitude particularly meaningful, especially if it witnesses to the richness of eremitical life beyond the common and narrow stereotypes that still plague the vocation through the agency of antisocial loners and misanthropes.

Guided by Stereotypes:

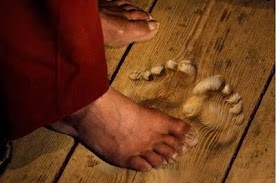

While a lot may have changed since the publication of Canon 603, I have the sense that most folks today are still guided by stereotypes in their understanding of this vocation. (I am not referring to you here, I don't know you at all!) Some have a knee-jerk reaction to anything that does not comport with those stereotypes, and reject such hermits out of hand without even giving c 603 life a hearing. But eremitical life has never been so univocal as that, and in every age and culture, eremites have been pioneers witnessing to the significance of the inner journey with, to, and for God's own sake in ways reflecting the diversity of these cultures and ages and the infinite potential and richness of a life lived in and from God. Sometimes, instead of stereotypes, people judge the eremitical life from external characteristics alone: Does the person live strictly alone or in a colony of hermits (or even in a house with one other person)? If in a colony or in a house with anyone else, then some say they can't really be considered hermits. Do they wear habits or not? If so, then they can't be considered hermits because they are not living lives "hidden from the eyes of men". Do they remain anonymous? If not, then again, they are not really hermits. How about their dwelling and church activity? If they live in a quiet apartment or are an integral part of their parish community of faith, and do not reside in a lonely place in the desert apart from a parish community, then they can't really be hermits, etc. Both solitude and an eremitical life of the "silence of solitude" are much richer, more diverse, and much more significant for every person than most narrow stereotypical understandings or those measured merely in terms of externals allow for.Of course, all eremitical lives reveal commonalities and some elements are sine qua non if one wants to live an eremitical life authentically. I once described these as the ridges and whorls making up any fingerprint, despite the meaningful differences from one print to the next. Canon 603 lists these constitutive ridges and whorls as follows: stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude, assiduous prayer and penance, profession of the evangelical counsels, a personal Rule of Life written by the hermit herself, all lived for the sake of the salvation of others and under the supervision of the diocesan Bishop. Each of us diocesan hermits lives ever more deeply into these elements, and we come to know by paying attention to the Holy Spirit that each one provides a doorway into a world wider and richer than anything we could have imagined.

Surprised by the Real Vocation:

For instance, when I was first reading about eremitical solitude, I could not have guessed that in its aloneness with God, it was a unique and rare form of community, nor could I have guessed it had to do with the redemption of isolation and alienation rather than their glorification or canonization! Similarly, I could not have imagined that the term "the world" refers not simply to the larger world outside the hermitage door, but instead, to that which is resistant to Christ, though especially and primarily, that reality within one's own heart that represents the most pernicious and overlooked instance of this "world". Neither could I have suspected that parish life would present me with innumerable instances of instruction in learning to love and be loved by others as Christ loved --- all critical to someone presuming to live a genuinely solitary contemplative life! Finally, I could not have even begun to suspect that my own brokenness would provide the fertile ground for a flowering of God's love in a way that allowed me to journey into the shadow of death and despair and find there the source of all hope, wholeness, and holiness. It was in this journey that hiddenness, stricter separation from the world, and the silence of solitude all came together as c 603, I believe, well understands. Underlying all of this, I could not have seen that the theology I did (both undergraduate, graduate, and post graduate), prepared me incredibly well for the paradox, not only of the Christ Event that stands at the heart of my faith, but of the eremitical life itself, where solitude means a profound engagement with God on behalf of others and entails a careful engagement with others on God's behalf.Learning to be the Hermit I am Called to be:

When I began living this life, I had certain ideas about what being a hermit meant, just as you have. There were tensions between those beliefs and the ways I felt called by God to be true to myself and to God. What was ironic was that moving more deeply into eremitical life was made possible within and through those tensions. For instance, I thought solitude meant living apart from a parish community. Over time, however, I discovered that the time I spent engaging with others as part of and on behalf of parish life, also drew me more deeply into my solitary life with God. I chose to teach Scripture to a parish community (and to some who join us from outside it), and in the process found that my time in solitude was more and more fruitfully centered in Scripture. My prayer was richer, the inner work I undertook in spiritual direction was even better supported, and my life with others was both appropriately limited and more intimate and loving. Also important was the reading I did, and the people I had conversations with on eremitical life. Beyond this, I continued working with my director, and in all of this, the question of whether I was still called to be a hermit was at least implicit. We explored the tensions I experienced, discerned how I could be true to myself and faithful to God and this vocation, and time and again, what became freshly clear was that I was following my path to and with God and could trust that. As my inner journey became deeper, sometimes more demanding, and ever more fruitful, the truth of my call was reaffirmed many times over, and this inner journey became clearly identified with the vocation's hiddenness. (Because my vocation is also a public one (one of those tensions I mentioned), I rejected superficial definitions of hiddenness associated with anonymity.) Discernment was ongoing; nothing about the way I live this vocation went unexamined, and was examined again whenever circumstances changed, or tensions occurred or increased. Eventually, what became entirely clear to me was something I had glimpsed early on, namely, I am a hermit embodying a life defined by c 603; so long as I live my life with integrity and faithfulness to God, I will remain a hermit.Same Ridges and Whorls, Unique Fingerprints:

This does not mean anything goes, of course, nor does it mean that I myself am the measure of the meaning of the constitutive elements of c 603. It means I must continue discerning what is right for me and, along with the Church, my sense of this ecclesial vocation according to the way God calls me to wholeness and holiness. I have done that since 1983 and will continue to do so in all of the ways that are helpful and necessary. Absolutely, I will need to let go of preconceived and possibly anachronistic notions of what constitutes eremitical life, and I will continue to revise the way I live the normative elements as circumstances and maturation in my inner life necessitates. Again, the constitutive elements of c 603 are not words with a single, fairly superficial meaning, but instead are doorways into rich, multi-layered realms the hermit explores as part of her commitment to God and to God's Church, and, in fact, to God's entire creation in eremitical life.Every hermit I know lives this life at least somewhat differently from every other hermit. Yes, there are the same ridges and whorls, the same constitutive elements as those made normative in c 603, but the way each of us embodies these ridges and whorls, our unique eremitical fingerprints themselves, will differ one from another. The activities you ask about help empower and give shape to my solitary exploration of C 603 in God. Should any one of them begin to detract or distract me from this journey, then I will let go of it.Living in the World Without Being of the World:

I have to say your question about living apart from the temporal world does not make sense to me. I am temporal, that is, I live in space and time. I am an embodied, historical being. That is what it means to be human. Yes, I am also empowered by the Holy Spirit to transcend space and time in some ways, but I am neither atemporal nor ahistorical, nor can I be. One dimension of my vocation is to allow God's will to be Emmanuel (God With us) to be realized ever more fully in and through my life. Another overlapping dimension of my vocation is to allow God to make me into someone who is prepared to be wholly united with God in a "new heaven and a new earth". A third dimension of my vocation is to assist others in committing to and living from and with that same God, His Gospel, and the New Creation, of which Jesus is the firstfruits (1Cor 15:23). Hermits embody the truth of Jesus' charge to every Christian to be in the world but not of it. I am committed to that goal, but I cannot do it by abandoning my own historical (spatio-temporal) nature. Indeed, given the importance of the Incarnation in revealing both God's unconditional, inexhaustible love and the fullest truth of humanity, and given my own place as a sharer in that mission of Jesus, how would I even begin to do that? Matter or materiality is not contrary to life in God. We believe in bodily resurrection and bodily assumption. We believe that in ways known only to God, embodied reality (whatever that looks like!) has a place in the very life of God because of Jesus' death, resurrection, and ascension. We recognize that when Paul speaks of being a spiritual being or a fleshly being, he is speaking of the dimension of reality that defines us so that being spiritual means the whole person under the power of the Holy Spirit, while being fleshly means the whole person under the power of sin. In either case, we are speaking of being an embodied person. One of the miraculous witnesses of the Eucharist is to the way Jesus, as risen Christ, is wholly and gloriously present in, and at the same time, wholly transcends mere bread and wine. Sometimes I wonder if this is a foretaste not just of heaven, but of the way a glorified reality will ultimately be comprised. After all, when we speak of our ultimate goal, it is of life in and with God, which will also be embodied. The Scriptures remind us that we look forward to a new heaven and earth in which this exhaustive union involves the whole of creation, where the entirety is glorified. (cf, Isaiah 66:22; 65:17, Rev 21:1, 2 Peter 3:13)

.jpg)