[[Hi Sister Laurel, thank you for telling your story from the perspective of using gifts vs being the gift. Two things surprised me a little. The first was the idea that the hiddenness of the eremitical life has to do mainly with the work God is doing within the hermit. This really is the vocation of the hermit and where else can it happen but in hiddenness? The second was that in letting go of a concern to use the gifts God has given us and instead focusing on the gift God makes of us we are involved in what the Gospel calls "dying to self"! I had never thought about it that way but this is the sense it made to me. The motto, "Let go and let God" fits here doesn't it?]]

[[Hi Sister Laurel, thank you for telling your story from the perspective of using gifts vs being the gift. Two things surprised me a little. The first was the idea that the hiddenness of the eremitical life has to do mainly with the work God is doing within the hermit. This really is the vocation of the hermit and where else can it happen but in hiddenness? The second was that in letting go of a concern to use the gifts God has given us and instead focusing on the gift God makes of us we are involved in what the Gospel calls "dying to self"! I had never thought about it that way but this is the sense it made to me. The motto, "Let go and let God" fits here doesn't it?]]

The Hiddenness of the Hermit Vocation:

Thanks for writing. You got it exactly right with regard to the hiddenness of the eremitical life! I especially liked your rhetorical question, ". . . where else can it happen but in hiddenness?" Most of the time when hermits speak about the hiddenness of their lives they speak about people not knowing they are hermits or doing things anonymously. Others speak of not wearing habits, not using titles or post-nomial initials and the like lest the hiddenness of the vocation be betrayed. I have written several times now about the tension between the hiddenness of the vocation and its public character --- its call to witness to the work of the Holy Spirit in the life of the Church in this way of life. All of these have some greater or lesser degree of validity but I think that when we recognize that eremitical life is about letting God do God's own silent and solitary work in the hiddenness of the human heart as we move more and more toward dwelling within his own heart in Christ, we have put our finger on the heart of the matter of eremitical hiddenness.

It seems to me that in every person's life God works silently in incredible hiddenness. The hermit commits her entire life to allowing this and witnessing to it. The very fact that she retires to a hermitage witnesses to her commitment to and faith in this hidden work of God. The fact that she embraces a life of the silence of solitude is a commitment that witnesses to it. Those of us who wear habits, use titles and post-nomial initials that prompt people to ask about our lives are a commitment and (paradoxically) witness to this incredible hiddenness. It is always striking to me that when people learn I am a hermit they tend to be completely off-footed. I noted that recently I played violin for a funeral held in our parish and that this was well-received. People understood this use of gifts and they wondered what I did here at the parish; they expected that I taught, perhaps music, or that I was a liturgist or any number of other things but they looked a bit stunned when they heard I was a hermit and rarely played violin this way. No one actually said, "Oh what a waste," of course; surprise and maybe puzzlement was what was generally expressed. I am hoping folks realized that the violin expressed and reflected what happens to my own heart in the ordinary silence and solitude of my hermitage.

It seems to me that in every person's life God works silently in incredible hiddenness. The hermit commits her entire life to allowing this and witnessing to it. The very fact that she retires to a hermitage witnesses to her commitment to and faith in this hidden work of God. The fact that she embraces a life of the silence of solitude is a commitment that witnesses to it. Those of us who wear habits, use titles and post-nomial initials that prompt people to ask about our lives are a commitment and (paradoxically) witness to this incredible hiddenness. It is always striking to me that when people learn I am a hermit they tend to be completely off-footed. I noted that recently I played violin for a funeral held in our parish and that this was well-received. People understood this use of gifts and they wondered what I did here at the parish; they expected that I taught, perhaps music, or that I was a liturgist or any number of other things but they looked a bit stunned when they heard I was a hermit and rarely played violin this way. No one actually said, "Oh what a waste," of course; surprise and maybe puzzlement was what was generally expressed. I am hoping folks realized that the violin expressed and reflected what happens to my own heart in the ordinary silence and solitude of my hermitage.

In any case, the gifts we occasionally use and those we relinquish in the name of our lives as hermits witness to the essential hiddenness of those lives and of the God powerfully at work there. We know that God works this way in every person's life but it seems to me that relatively few people actually commit to revealing this by embracing an essential hiddenness. Cloistered nuns and monks do so, hermits do so; it is a witness our world needs --- and one that throws folks off-balance when they meet it face to face. The Kingdom of God comes in this way. It grows silently in the darkness and night when we can do nothing but trust in the One who is its source. It bursts forth when we have reached the limits of our own patience, when we have finally relinquished any pretense of control or even understanding. It comes in victory at the same time we admit defeat and steals upon us -- gently silencing the prayer that storms heaven so that heaven can simply sing within us.

Prayer is certainly the hermit's main ministry but only if it is genuinely the work she allows God to do in, with, and through her, the work which allows her to set her own concerns, frailties, strengths, and even her talents and gifts aside so to speak so that the hidden work and presence of God may flourish within her. I have written before that it is the hermit's very vocation to become God's own prayer in our world; in fact, that is really the fundamental vocation of every person because it is the thing which characterizes authentic humanity. Hermits, it seems to me, undertake this with a special dedication in a way which is largely stripped of the activities and ministries which, while usually revelatory, may actually distract attention from that foundational presence at work in the solitary silence of every human heart. See also, Essential Hiddenness: A Call to extraordinary ordinariness for a post on the universality of this call.

God-given gifts and Dying to Self:

Ordinarily we speak of dying to self in terms of using our gifts generously and selflessly. This is an entirely valid and critical piece of what dying to self really means. However, I think the idea of letting go of significant gifts God has given us so that who we are ourselves, that is, so that we are who God makes us to be most fundamentally, is the real witness of our lives; it is a special and even more radical kind of dying to self peculiar to the eremitical life --- though we find suggestions of it in old age, chronic illness, etc. This really is a new insight for me --- one, that is, I have only just begun thinking consciously about in connection with the idea that the hermit's life is an essentially hidden one. It is a paradox because at the same time we let go of those gifts we become freer to use them without pressure or self-consciousness should appropriate opportunities arise. Even so, we are not our gifts, not most fundamentally, nor is our life ultimately about a struggle to protect or even to use those gifts. And when we are deprived of those gifts or of the ability to use them by illness or other life circumstances the deepest or foundational meaning and mystery of our lives can become clear. This too is a form of dying to self --- perhaps the most radical form short of the physical death of red martyrdom.

Ordinarily we speak of dying to self in terms of using our gifts generously and selflessly. This is an entirely valid and critical piece of what dying to self really means. However, I think the idea of letting go of significant gifts God has given us so that who we are ourselves, that is, so that we are who God makes us to be most fundamentally, is the real witness of our lives; it is a special and even more radical kind of dying to self peculiar to the eremitical life --- though we find suggestions of it in old age, chronic illness, etc. This really is a new insight for me --- one, that is, I have only just begun thinking consciously about in connection with the idea that the hermit's life is an essentially hidden one. It is a paradox because at the same time we let go of those gifts we become freer to use them without pressure or self-consciousness should appropriate opportunities arise. Even so, we are not our gifts, not most fundamentally, nor is our life ultimately about a struggle to protect or even to use those gifts. And when we are deprived of those gifts or of the ability to use them by illness or other life circumstances the deepest or foundational meaning and mystery of our lives can become clear. This too is a form of dying to self --- perhaps the most radical form short of the physical death of red martyrdom.

I think hermits have known this right along. It is what allows them to use the term "white martyrdom" for their lives. I have written here that I once thought of contemplatives and hermits as selfish rather than selfless. Back then I was thinking of the multitude of wasted gifts and of some sort of failure to honor them but I was not thinking of a life which explicitly honored the giver of all gifts in a more transparent way or was a naked expression of (dependence on) that giver and the redemption he occasions in us. At the same time I was very young; I had not really faced a situation where my own God-given gifts were either unusable or where, in my brokenness, emptiness, and incapacity, I knew more fully and clearly my own need for radical redemption --- much less had I come to actually know that redemption.

Only as I came face to face with these and the immense question "WHY?!" that drove me did I begin to sense that eremitical life could "make sense of the whole of my life." My sense of this, however, was still inchoate; it was as unformed as my own eremitical identity for I was not, in any sense of the term, a hermit. In time, and especially in the silence of solitude, God did with my life what the Gospel promises and proclaims. He loved me into wholeness and continues to do so. That hidden, unceasing, and unconquerable redemptive Love-in-act is what my vocation witnesses to. Hermits have seen right along that their witness is more fundamental and radical than even the use of God-given gifts for the sake of others can make clear.

One of the reasons the hermit life will always be rare is because we need people who use their God-given gifts in the multitude of ways which enrich our lives every day. In no way am I suggesting that such gifts are unimportant or, generally speaking, should not be used in assisting in the coming of the Kingdom of God. This is the usual way we cooperate with God and reveal God's life to others.

One of the reasons the hermit life will always be rare is because we need people who use their God-given gifts in the multitude of ways which enrich our lives every day. In no way am I suggesting that such gifts are unimportant or, generally speaking, should not be used in assisting in the coming of the Kingdom of God. This is the usual way we cooperate with God and reveal God's life to others.

But at the same time there will always be a few of us who have come to a place where chronic illness (or whatever else!) made this impossible; and yet, through a Divine mercy and wisdom we can hardly believe, much less describe, we have been redeemed and become gifts more precious than any or all of the individual talents we once carefully developed and shepherded. Through a more radical and counter-cultural kenosis (self-emptying), in the hiddenness of a life more fundamentally about being made gift than about using our talents, hermits are called to witness to the inexhaustible, transcendent, and redemptive reality dwelling in the very core of our being -- the infinitely loving source and ground of our lives. Those redeemed and transfigured lives say, "God alone is enough!" With St Paul (who himself was stripped and emptied by life's circumstances and who spent time in the desert learning to see the new kind of sense his life held in light of the crucified Christ), we proclaim in the starkest way we can, "I, yet not I but Christ within me!"

28 July 2015

More on the Hiddenness of the Hermit Vocation

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

8:30 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: 'WHY?!', Canon 603, Eremitical Hiddenness, Eremitism and Hiddenness, Essential Hiddenness, silence of solitude, Silence of Solitude as Charism

26 July 2015

On the Distinction Between Anchorites and Hermits

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I was recently reading a book on the history of Christian hermits. The

book made the distinction between hermits and anchorites. I have read about this

distinction before and it does seem present in the Middle Ages. Certain saints

are described as either anchorites OR hermits. Not both. It would seem that the

vocations are similar but different.

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I was recently reading a book on the history of Christian hermits. The

book made the distinction between hermits and anchorites. I have read about this

distinction before and it does seem present in the Middle Ages. Certain saints

are described as either anchorites OR hermits. Not both. It would seem that the

vocations are similar but different.

This book said that in the Middle

Ages anchorites (either male or female) were known for their intense seclusion.

Whereas hermits lived in solitude but were often integrated into the local

community. For example, they would receive visitors, do service for the

community like teaching, fixing roads and bridges and tend to the sick and poor

all the while living in solitude and living an intense life of prayer.

Apparently this was especially the case in England and Scotland during the

Middle Ages.

There was a clear distinction between anchorites and

hermits. Anchorites also seemed to be under certain canons and ecclesial

discipline whereas hermits were a little more on the fringe (while still being

faithful to the Church). From what I've read, hermits and their way of

life has varied in the Church. Yes, solitude and intense prayer are essential

but their level of interaction with "the world" has varied. Not so with

anchorites. It seems their calling is predicated on intense solitude and

ecclesial approval.

As such, do you think canon 603 has confused the

two vocations? Could there be an argument for reforming the canon to reflect the

distinction between hermits and anchorites? Looking at your blog it seems that

there may be many people called to a hermit vocation that would include

solitude, intense prayer and celibacy whilst still serving the community like

the hermits of the Middle Ages. In other words, some seem called to be hermits

but not anchorites. Canon 603 does not allow for this distinction. Perhaps as

the eremetic vocation is reborn in the Church these distinctions will become

clearer. ]]

Thanks for writing again and for the interesting questions. I don't think a distinction between the two is absent throughout the history of eremitism, but, despite the term anachoresis meaning withdrawal, neither do I believe the real distinction is as was presented in the book you read. (My sense is originally the two words, hermit and anchorite were interchangeable. Only over time and especially as urban hermits -- especially women urban hermits -- became a reality did distinctions develop.) Still, both solitary hermits and anchorites lived lives of intense prayer and solitude (they all withdraw or are defined by anachoresis for the purpose of prayer) but the difference between the two seems to be in the degree and even more, in the kind of stability the two embraced.

Thanks for writing again and for the interesting questions. I don't think a distinction between the two is absent throughout the history of eremitism, but, despite the term anachoresis meaning withdrawal, neither do I believe the real distinction is as was presented in the book you read. (My sense is originally the two words, hermit and anchorite were interchangeable. Only over time and especially as urban hermits -- especially women urban hermits -- became a reality did distinctions develop.) Still, both solitary hermits and anchorites lived lives of intense prayer and solitude (they all withdraw or are defined by anachoresis for the purpose of prayer) but the difference between the two seems to be in the degree and even more, in the kind of stability the two embraced.

Anchorites tended to embrace a much more constrained physical stability so that they were required to remain within a single small house or even a single room. Sometimes they were even locked or walled into such a place. Otherwise, however, both groups dealt with others (sometimes the degree of interaction was relatively extensive); similarly both were often approved to some extent by diocesan canons and local Bishops. Hermits (always men) who traveled from place to place were often granted the hermit tunic and permits to beg and preach by the local ordinary, for instance. But anchorites (who could include both women and men) lived their solitude within a fixed abode; hermits (who were, as you say, more marginal) could wander from town to town or otherwise live their solitude in less physically constrained ways. (Part of this, of course, was due to the fact that women living on their own (apart from the household of a husband) were suspicious to folks and this resulted in practices which brought anchorites under greater church control while hermits could mainly do and go as they pleased.)

Because anchorites tended to live in the midst of villages with a window on the Church altar and one on the village square, they were often unofficial counselors, spiritual directors, a friendly pastoral ear, teachers, wisdom figures, preachers (as, again, were itinerant hermits), etc. Contrary to what you have concluded, while some were certainly secluded like the modern day Nazarena (oftentimes reforms were attempted by priests who wrote Rules for them limiting and regulating their contact with others) the very fact that such reforms were seen as necessary confirms that anchorites were, generally speaking, not so secluded as all that. The Ancrene Wisse seems to have been written for just such a reason. See also, for instance, Mulder-Bakker's Lives of the Anchoresses, The Rise of the Urban Recluse in Medieval Europe, Liz McEvoy's, Anchoritic Traditions of Medieval Europe, or Ann K Warren's, Anchorites and Their Patrons in Medieval England for portraits of their diversity. See also Thomas Matus, OSB Cam's Nazarena for a wonderful portrait of this anchoress and a detailed picture of strict anachoresis and physical stability.

(By the way, let me be clear that I am not including in my own thoughts here the lone individuals who simply go off on their own and even today are called "hermits" despite their lives often being little more than an expression of personal eccentricity, misanthropy, and disedifying individualism. Those have always existed and perhaps always will, but they can muddy the discussion, I think, especially with regard to canon 603 and the type of solitude it calls for. Today we would not call these folks hermits except in a common and somewhat stereotypical sense. Excluding them from the discussion changes the terms significantly I think. And of course canon 603 does NOT define or govern this kind of "hermit.")

Even so, I don't believe canon 603 has confused the two vocations. When it says "the eremitical or anchoritic life" it may be using the oldest synonymous sense but it can also certainly be seen to mean eremitical life which includes but is not limited to the intense physical stability of the anchorite. I am not sure why you conclude "canon 603 does not allow this distinction". Canon 603 seems to me to be flexible enough to allow for both. It would depend entirely upon the Rule written by the individual and approved by the local diocesan Bishop. In fact, I would argue this is a real strength of canon 603. It does not unnecessarily multiply categories even as the requirement for the individual's own Rule accommodates personal differences and the charismatic work of the Holy Spirit including degree of contact with and ministry to others and the degree of physical stability. Neither does canon 603 distinguish between male and female and it has to be remembered that in much of the history of eremitical life women were not allowed to become solitary hermits living in mountains and forests. They had to live as anchorites in urban contexts. (Men could do either.) Again, I think this flexibility and universality is a real strength of canon 603.

Even so, I don't believe canon 603 has confused the two vocations. When it says "the eremitical or anchoritic life" it may be using the oldest synonymous sense but it can also certainly be seen to mean eremitical life which includes but is not limited to the intense physical stability of the anchorite. I am not sure why you conclude "canon 603 does not allow this distinction". Canon 603 seems to me to be flexible enough to allow for both. It would depend entirely upon the Rule written by the individual and approved by the local diocesan Bishop. In fact, I would argue this is a real strength of canon 603. It does not unnecessarily multiply categories even as the requirement for the individual's own Rule accommodates personal differences and the charismatic work of the Holy Spirit including degree of contact with and ministry to others and the degree of physical stability. Neither does canon 603 distinguish between male and female and it has to be remembered that in much of the history of eremitical life women were not allowed to become solitary hermits living in mountains and forests. They had to live as anchorites in urban contexts. (Men could do either.) Again, I think this flexibility and universality is a real strength of canon 603.

What I am saying is that I don't personally see any need for a codified

distinction. Partly that's because I only know of one diocesan hermit who calls herself an

anchoress; she is completely free to do that under the canon and this speaks to the canon's sufficiency in this matter. Given the relative rarity of eremitical vocations of any

sort a codified distinction seems relatively meaningless to me --- especially since,

whether they are hermits or anchorites, those admitted to canonical standing must

live the same essential elements of canon 603. Again, the differences will be defined by or otherwise reflected in the individual's Rule. I also mean that unless the definition of the anchorite or anchoress is "the hermit committed to living increased physical stability", the term's use as something distinct tends not to make sense to me today. After all, we already have the descriptor "recluse" to characterize the hermit or anchorite who is almost wholly without contact with others while both men and women under canon 603 are free to live as urban hermits or as solitary hermits in deserts, forests, or mountains.

In any case, each eremitical vocation will probably involve greater withdrawal at some points and greater contact with others at other points in the hermit's life. Again, canon 603 allows for this within given limits and provided there is adequate discernment involved. A multiplication of categories and distinctions might tend to stifle this pneumatic or charismatic quality of the contemporary solitary eremitical vocation. Throughout the history of the eremitical vocation the all-too-human attempt to codify and qualify (read control!) the movement of the Spirit resulted in somewhat "hardened" categories which could miss the diversity and freedom of the vocation --- part of the reason your author describes anchoritism in one way and mine describe its essence in another! Terms which were mainly descriptive (and helpful when merely descriptive) were made to be prescriptive and applied differently to women and men. As noted, Canon 603 is beautifully written in the way it combines non-negotiable elements and the flexibility of the hermit's own Rule. At least in regard to this discussion, I believe it would be a serious (and probably futile) mistake to codify definitions beyond the non-negotiable elements it already requires.

In any case, each eremitical vocation will probably involve greater withdrawal at some points and greater contact with others at other points in the hermit's life. Again, canon 603 allows for this within given limits and provided there is adequate discernment involved. A multiplication of categories and distinctions might tend to stifle this pneumatic or charismatic quality of the contemporary solitary eremitical vocation. Throughout the history of the eremitical vocation the all-too-human attempt to codify and qualify (read control!) the movement of the Spirit resulted in somewhat "hardened" categories which could miss the diversity and freedom of the vocation --- part of the reason your author describes anchoritism in one way and mine describe its essence in another! Terms which were mainly descriptive (and helpful when merely descriptive) were made to be prescriptive and applied differently to women and men. As noted, Canon 603 is beautifully written in the way it combines non-negotiable elements and the flexibility of the hermit's own Rule. At least in regard to this discussion, I believe it would be a serious (and probably futile) mistake to codify definitions beyond the non-negotiable elements it already requires.

Excursus: I very much appreciate your putting "the world" in quotes when you describe the hermits' level of interaction with the realm outside the hermitage because we have talked about this before. Still, quotation marks or not, it remains a mistake to automatically call everything outside a hermitage, monastery, or convent "the world" when most truly, worldliness is a description of a resistance to Christ we primarily carry in our hearts. Perhaps a better term for the reference in your question is the longer, "the world (or just "those") outside the anchorhold", etc. So, while I thought the quotation marks were a definite improvement, if you merely mean "the world outside the anchorhold or hermitage" spelling it out might be a yet better choice.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:18 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Anchoritism, Canon 603, Stability

24 July 2015

Guidelines for Readers Asking Questions

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

7:27 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: guidelines

On the Distinction Between Using Gifts and Being the Gift

[[Hi Sister. I've been reading what you wrote on chronic illness as vocation. I wondered why God would give a person gifts they could never really use. And if their gifts can't be used then how do they serve or glorify God? I mean I do believe people who can't use God-given gifts still serve God but we are supposed to use our gifts and what if we can't? Since you are a hermit do you ever feel that you cannot use your gifts? Does it matter? Does canonical standing make better use of your gifts than non-canonical standing? I hope this is not gibberish!]]

[[Hi Sister. I've been reading what you wrote on chronic illness as vocation. I wondered why God would give a person gifts they could never really use. And if their gifts can't be used then how do they serve or glorify God? I mean I do believe people who can't use God-given gifts still serve God but we are supposed to use our gifts and what if we can't? Since you are a hermit do you ever feel that you cannot use your gifts? Does it matter? Does canonical standing make better use of your gifts than non-canonical standing? I hope this is not gibberish!]]

These are great questions and no, not gibberish at all. The pain of being given gifts which we may not be able to use because of chronic illness or other life circumstances is, in my experience, one of the most difficult and bewildering things we can know. The question "WHY?!!" is one of those we are driven to ask by such situations. We ask it of God, of the universe, of the silence, of friends and family, of books and teachers and pastors and ministers; we ask it of ourselves too though we know we don't have the answer. In one way and another we ask it in many different ways of whomever will listen --- and sometimes we force people to listen to the screams of anguish our lives become as we embed this question in all we are and do. Whether we act out, withdraw, retreat into delusions, turn seriously to religion or philosophy, resort to crime, become workaholics for whom money is the measure of meaning, create great works of art, or whatever else we do, the question, WHY?! often stands at the heart of our searching, activism, depression, confusion, and pain. This is true even when our lives have not been derailed by chronic illness, but of course when that or other catastrophic events occur to us the question assumes a critical importance. And of course, we can live years and years without finding an answer. I think you will understand when I say that "WHY?!" is the question which, no matter how it is posed throughout our lives, we each are.

One thing I should be clear about is that God gives us gifts because he wills us to use them and is delighted when we can and do so. I do not believe God gives gifts to frustrate us or to be wasted. But, as Paul puts the matter, and as we know from experience, there are powers and principalities at work in our world and lives which are not of God. God does not will chronic illness, for instance. Illness is a symptom and consequence of sin --- that is, it is the result of being estranged to some extent from the source and ground of life itself. Even so, though God does not will our illness, he will absolutely work to bring good out of it to whatever degree he can. Especially, God will work so that illness is no longer the dominant reality of our lives. It may remain, but where once it was the defining reality of our lives and identity, God will work so that grace becomes the dominant theme our lives sings instead; illness, though still very real perhaps, then becomes a kind of subtext adding depth and poignancy but lacking all pretensions of ultimacy.

One thing I should be clear about is that God gives us gifts because he wills us to use them and is delighted when we can and do so. I do not believe God gives gifts to frustrate us or to be wasted. But, as Paul puts the matter, and as we know from experience, there are powers and principalities at work in our world and lives which are not of God. God does not will chronic illness, for instance. Illness is a symptom and consequence of sin --- that is, it is the result of being estranged to some extent from the source and ground of life itself. Even so, though God does not will our illness, he will absolutely work to bring good out of it to whatever degree he can. Especially, God will work so that illness is no longer the dominant reality of our lives. It may remain, but where once it was the defining reality of our lives and identity, God will work so that grace becomes the dominant theme our lives sings instead; illness, though still very real perhaps, then becomes a kind of subtext adding depth and poignancy but lacking all pretensions of ultimacy.

This is really the heart of my answer to your questions. Each of us has many gifts we would like to develop and use. I think most of us have more gifts than we can actually do that with. For instance, if I choose to play violin and thus spend time and resources on lessons, practice periods, music, and time with friends who also play music, I may not be able to spend the time I could spend on writing or theology, or even certain kinds of prayer I also associate with divine giftedness. This is a normal situation and we all must make these kinds of choices as we move through life. Still, while we must make decisions regarding which gifts we will develop and which we will allow to lay relatively fallow there is a deeper choice involved at every moment, namely, what kind of person will we be in any case? When chronic illness takes the question of developing and using specific gifts out of our hands, when we cannot use our education, for instance, or no longer work seriously in our chosen field, when we cannot raise a family, hold a job, or perhaps even volunteer at Church in ways we might once have done, the question that remains is that of who we are and who will we be in relation to God.

This is really the heart of my answer to your questions. Each of us has many gifts we would like to develop and use. I think most of us have more gifts than we can actually do that with. For instance, if I choose to play violin and thus spend time and resources on lessons, practice periods, music, and time with friends who also play music, I may not be able to spend the time I could spend on writing or theology, or even certain kinds of prayer I also associate with divine giftedness. This is a normal situation and we all must make these kinds of choices as we move through life. Still, while we must make decisions regarding which gifts we will develop and which we will allow to lay relatively fallow there is a deeper choice involved at every moment, namely, what kind of person will we be in any case? When chronic illness takes the question of developing and using specific gifts out of our hands, when we cannot use our education, for instance, or no longer work seriously in our chosen field, when we cannot raise a family, hold a job, or perhaps even volunteer at Church in ways we might once have done, the question that remains is that of who we are and who will we be in relation to God.

The key here is the grace of God, that is, the powerful presence of God. Illness does not deprive us of the grace of God nor of the capacity to respond to that grace. In my own process of becoming a hermit, as you know, I had had my own life derailed by chronic illness. Fortunately, I had prepared to do Theology and loved systematics so that I read Theology even as illness deprived me of the possibility of doing this as a profession. I was also "certain" that I was called to some form of religious life; these two dimensions were gifts that helped me hold onto a perspective that transcended illness and disability, and at least potentially, promised to make sense of these.

The key here is the grace of God, that is, the powerful presence of God. Illness does not deprive us of the grace of God nor of the capacity to respond to that grace. In my own process of becoming a hermit, as you know, I had had my own life derailed by chronic illness. Fortunately, I had prepared to do Theology and loved systematics so that I read Theology even as illness deprived me of the possibility of doing this as a profession. I was also "certain" that I was called to some form of religious life; these two dimensions were gifts that helped me hold onto a perspective that transcended illness and disability, and at least potentially, promised to make sense of these.

My professors (but especially John C Dwyer) had introduced me to an amazing theology of the cross (both Pauline and Markan) which focused on a soteriology (a theology of redemption) stressing that even the worst that befalls a human being can witness to the redemption possible with God. In Mark's version of the gospel, the bottom line is that when all the props are kicked out, God will bring life out of death and meaning out of senselessness. In Paul's letters I was reminded many times that the center of things is his affirmation: "My (i.e., God's) grace is sufficient for you; my power is made perfect in weakness." Meanwhile, at one point I began working with a spiritual director who believed unquestioningly in the power of God alive in the core of our being and provided me with tools to help allow that presence to expand and triumph in my heart and life. In the course of our work together, my own prayer shifted from being something I did (or struggled to do!) to something God did within me. (This shift was especially occasioned and marked by the prayer experience I have mentioned here before.) In time I became a contemplative but at this point in time illness still meant isolation rather than the communion of solitude.

All of these pieces and others came together in a new way when I read canon 603 and began considering eremitical life. The eremitical life is dependent upon God's call of course, but everything about it also witnesses to the truth that God's grace is enough for us and God's power is perfected in weakness. When we speak about the hiddenness of the life it is this active and powerful presence of God who graces us that is of first concern. I have many gifts, but in this life there is no doubt that they generally remain hidden and many are even entirely unused while the grace of God makes me the hermit I am called to be. Mainly this occurs in complete hiddenness. I may think and write about this life; I may do theology and a very little adult faith formation for my parish; I may do a limited amount of spiritual direction, play some violin in an orchestra, and even write on this blog and for publication to some extent --- though never to the extent I might have done these things had chronic illness not knocked my life off the rails. But the simple fact is if I were unable to do any of these things my vocation would be the same. I am called to BE a hermit, a whole and holy human being who witnesses to the deepest truth of our lives experienced in solitude: namely, God alone is sufficient for us. We are made whole and completed in the God who seeks us unceasingly and will never abandon us.

All of these pieces and others came together in a new way when I read canon 603 and began considering eremitical life. The eremitical life is dependent upon God's call of course, but everything about it also witnesses to the truth that God's grace is enough for us and God's power is perfected in weakness. When we speak about the hiddenness of the life it is this active and powerful presence of God who graces us that is of first concern. I have many gifts, but in this life there is no doubt that they generally remain hidden and many are even entirely unused while the grace of God makes me the hermit I am called to be. Mainly this occurs in complete hiddenness. I may think and write about this life; I may do theology and a very little adult faith formation for my parish; I may do a limited amount of spiritual direction, play some violin in an orchestra, and even write on this blog and for publication to some extent --- though never to the extent I might have done these things had chronic illness not knocked my life off the rails. But the simple fact is if I were unable to do any of these things my vocation would be the same. I am called to BE a hermit, a whole and holy human being who witnesses to the deepest truth of our lives experienced in solitude: namely, God alone is sufficient for us. We are made whole and completed in the God who seeks us unceasingly and will never abandon us.

Paradoxically a huge part of my readiness for perpetual eremitical vows was coincident with coming to a place where I did not really need the Church's canonical standing except to the extent I was bringing them a unique gift. You see, I knew that the Holy Spirit had worked in my life to redeem an isolation and alienation occasioned mainly by chronic illness. THAT was the gift I was bringing the Church, the charism I was seeking to publicly witness to in the name of the Church by seeking public profession and consecration. That the Holy Spirit worked this way in my life in the prayer and lectio of significant solitude seems to me to be precisely what constitutes the gift of eremitical life. (Of course canonical standing and especially God's consecration has also been a great gift to me but outlining that is another, though related, topic.)

Thus, when I renewed my petition to the Diocese of Oakland regarding admission to perpetual profession and consecration in the early 2000's, eremitical solitude had already transformed my life. I was already a hermit not because of any particular standing but because I lived the truth of redemption mediated to me in the silence of solitude. I sought consecration because now I clearly recognized this gift belonged to the Church and was meant for others; public standing in the consecrated state made that possible in a unique way. I was not seeking the Church's approval of this gift so I could be made a hermit "with status" so much as I was seeking a way to make a genuine expression of eremitical life and the redemption of isolation and meaninglessness it represented better known and accessible to others. That, I think, is the real importance of canonical standing, especially for the hermit; it witnesses more to the work of the Holy Spirit within the Church, more to the contemplative primacy of being over doing, and thus, less to the personal gifts of the person being professed and consecrated.

By the way, along the way I do use many of the gifts God has given me to some extent. Yesterday, for instance, I was able to play violin for a funeral Mass. I don't do this often at all because I personally prefer to participate in Mass differently than this, but it was a joy to do for friends in the parish. (A number of people who really do know me pretty well commented, "I didn't know you played the violin!") Today I did a Communion service and reflection as I do many Fridays during the year. Often times, as I have noted here before, I write reflections on weekly Scripture lections, and of course I write here and other places and do spiritual direction. This allows me to use some of my theology for others but even more fundamentally it is an expression of who I am in light of the grace of God in my life. Even so, the important truth is that the eremitical vocation (and, I would argue, any vocation to chronic illness!) is much more about being the gift God makes of us --- no matter how hidden eremitical life or our illness makes that gift --- than it is a matter of focusing on or being anxious about using or not using the gifts God has given us.

By the way, along the way I do use many of the gifts God has given me to some extent. Yesterday, for instance, I was able to play violin for a funeral Mass. I don't do this often at all because I personally prefer to participate in Mass differently than this, but it was a joy to do for friends in the parish. (A number of people who really do know me pretty well commented, "I didn't know you played the violin!") Today I did a Communion service and reflection as I do many Fridays during the year. Often times, as I have noted here before, I write reflections on weekly Scripture lections, and of course I write here and other places and do spiritual direction. This allows me to use some of my theology for others but even more fundamentally it is an expression of who I am in light of the grace of God in my life. Even so, the important truth is that the eremitical vocation (and, I would argue, any vocation to chronic illness!) is much more about being the gift God makes of us --- no matter how hidden eremitical life or our illness makes that gift --- than it is a matter of focusing on or being anxious about using or not using the gifts God has given us.

In other words my life glorifies God and is a service to God's People even if no one has a clue what specific gifts God has given me because it reveals the power of God to redeem and transfigure a reality fraught with sin, death, and the power of the absurd. A non-eremitical vocation to chronic illness does the same thing if only one can allow God's grace to work in and transfigure them. We ourselves as covenant partners of God in all things then become the incarnate "answer" to the often-terrible question, "WHY?!!" In Christ, in our graced and transfigured lives, this question ceases to be one of unresolved torment; instead, it becomes both an invitation to and an instance of hope-filled witness and joyful proclamation. "WHY??" So that Christ might live in me and in me triumph over all that brings chaos and meaninglessness to human lives. WHY?1! So that the God of life may triumph over the powers of sin and death in us, the Spirit may transform isolation into genuine solitude in us, and the things that ordinarily separate us from God may become sacraments of God's presence and inescapable, unconquerable love in us!

I hope this is helpful and answers your questions.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:03 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: 'WHY?!', Charism of the Diocesan Hermit, Eremitical Hiddenness, Essential Hiddenness, Silence of Solitude as Charism, vocation to being ill in the church

13 July 2015

Diocesan Hermits in the Archdiocese of Seattle?

Thanks for your questions. The simplest answer re the canonical standing of the person in question is to ask her! That is always the first step. If this is somehow inadequate or is impossible, then the next step is to contact the local parish and see if they know the answer. Finally, you can call the chancery and ask them if there is a consecrated (c 603) hermit living on Vashon Island. If you know the person by name they will tell you whether she is a diocesan hermit and usually whether she is in good standing with the diocese, but they are not going to give you any further details regarding the person if they know her at all. If they ask if there are problems just let them know you merely want to verify the person's canonical standing unless (as you seem to imply) there is something more involved.

The Archdiocese of Seattle has at least one diocesan hermit that I know of. But he is male; his name is Brother Jerry Cronkhite and he was professed on May 14, 2012 in the Cathedral of St James. I mention this to indicate that the Archdiocese HAS used canon 603 and therefore are clearly open to doing so. Some have tried to argue that some dioceses choose "the private route" rather than c 603, so I want to underscore this argument is especially specious in this case under the current archbishop! I know of two lay hermits either in Seattle or the Tacoma area close by Vashon Island. Still, for information on diocesan hermits (solitary consecrated hermits) your best source is the chancery. We diocesan hermits in the US are a small 'community' and a small number of those do belong to the Network of Diocesan Hermits, but I doubt any one of us knows all or even most of the others. (By the way, there is no central data base on c 603 hermits. Rome has begun keeping statistics on us but at this point, it is only the individual dioceses that have the information on those professed in the hands of local Bishops.)

The Archdiocese of Seattle has at least one diocesan hermit that I know of. But he is male; his name is Brother Jerry Cronkhite and he was professed on May 14, 2012 in the Cathedral of St James. I mention this to indicate that the Archdiocese HAS used canon 603 and therefore are clearly open to doing so. Some have tried to argue that some dioceses choose "the private route" rather than c 603, so I want to underscore this argument is especially specious in this case under the current archbishop! I know of two lay hermits either in Seattle or the Tacoma area close by Vashon Island. Still, for information on diocesan hermits (solitary consecrated hermits) your best source is the chancery. We diocesan hermits in the US are a small 'community' and a small number of those do belong to the Network of Diocesan Hermits, but I doubt any one of us knows all or even most of the others. (By the way, there is no central data base on c 603 hermits. Rome has begun keeping statistics on us but at this point, it is only the individual dioceses that have the information on those professed in the hands of local Bishops.)The conclusion and accusation that one is a "fake hermit" is a serious one. The charge ought not be leveled without real cause. While the term Catholic Hermit is authoritatively used by hermits with public vows and consecrations to indicate they live as hermits in the name of the Church, there are a handful of lay hermits (hermits in the lay state of life) who use the descriptor without having been authorized to do so. Some simply don't realize what they are doing is inappropriate. The person you are speaking of may well be a lay Catholic and hermit with or without private vows. The lay eremitical life, when lived authentically, is an entirely valid way to live eremitical life within the Church; it simply means the baptized person is living a private commitment in the lay state. She is not a religious (though she may be discerning admission to canon 603 with the diocese) and cannot claim to be living the eremitical life in the name of the Church. Still such a hermit lives her life as a Catholic lay person and represents a significant and living part of the eremitical tradition. Such a calling is to be esteemed.

Unfortunately, it cannot be denied that some individuals and some lay hermits do consciously and falsely try to pass themselves off as professed Religious or consecrated hermits. They either do know what they are doing is inappropriate and don't care, or they are wholly ignorant of the meaning of what they are doing I guess. Some do seem to believe one becomes a religious by making private vows --- which is simply not the case. Some seem to need a way to validate the failures in their own lives or desire a way to "belong" or have status they have not been granted otherwise (for genuine ecclesial standing is extended to the person and embraced freely by them; it is never merely taken). Some relative few use this as a way to beg for money or scam others. Others live isolated lives which are nominally Catholic, but without a Sacramental life or any rootedness in the local community. They validate this with the label 'hermit' but, whether lay persons or not, they are not living eremitical lives as understood and defined by the Church. Even so, let me reiterate, the conclusion of fraud is not one a person ought to leap to nor come to without serious cause.

By the way, one final possibility exists. You asked if Catholic hermits and canonical hermits are the same thing and the answer is yes. All Catholic hermits are canonical and live their vocation in the name of the Church. But some of these are solitary (c 603) and others belong to canonical communities (institutes). If the hermit you are speaking about belongs to a canonical community but is, for some valid reason, living on her own (say, on exclaustration while trying the eremitical vocation, for instance), then she will tell you what community she is professed with and be able to name her legitimate superior. (If she is lay person or former religious working with the Archdiocese to discern a vocation to canonical eremitism then she will tell you that too.) Again, while one should not pry, public vocations are just that and religious are answerable for these. Her identity, if she claims to be publicly professed, shouldn't be a secret, especially if she wishes to be known as a hermit. Similarly one shouldn't simply contact the chancery for any little thing without meaningful justification; however, if you have significant concerns for or about this person, then, presuming you have spoken to the person herself first to clarify matters, you can raise those with her legitimate superior or with Archbishop Sartain or the Vicar for Religious in the Archdiocese at the same time.

So, to summarize, in your situation, the simplest way to determine if the hermit in question is a canonical hermit and thus too, a Catholic Hermit who lives her life in the name of the Church, is to ask her whether she is a lay hermit (perhaps but not necessarily privately vowed or dedicated) or publicly professed and consecrated; if she says the latter then you may ask her who her legitimate superior is. Diocesan hermits will always name the local diocesan Bishop as their legitimate superior for their vows were made in his hands. FYI, it will not be a Bishop in another diocese, nor will it be another priest, or a spiritual director (even if this is a bishop), for instance. Nor, again, will a canonical hermit ever tell you her diocese doesn't require legitimate superiors or has chosen to go the "private route." If the diocese has not used canon 603 yet (again, not applicable to the Archdiocese of Seattle since they have at least one c 603 hermit) and the person has private vows they are NOT made under the auspices of the diocese per se. If questions or serious concerns remain turn to the parish and if necessary, to the chancery itself. Ask to speak to the Vicar for Religious (or the Vicar for Consecrated Life). S/he will certainly know the person if they are a c 603 (publicly professed solitary) hermit.

So, to summarize, in your situation, the simplest way to determine if the hermit in question is a canonical hermit and thus too, a Catholic Hermit who lives her life in the name of the Church, is to ask her whether she is a lay hermit (perhaps but not necessarily privately vowed or dedicated) or publicly professed and consecrated; if she says the latter then you may ask her who her legitimate superior is. Diocesan hermits will always name the local diocesan Bishop as their legitimate superior for their vows were made in his hands. FYI, it will not be a Bishop in another diocese, nor will it be another priest, or a spiritual director (even if this is a bishop), for instance. Nor, again, will a canonical hermit ever tell you her diocese doesn't require legitimate superiors or has chosen to go the "private route." If the diocese has not used canon 603 yet (again, not applicable to the Archdiocese of Seattle since they have at least one c 603 hermit) and the person has private vows they are NOT made under the auspices of the diocese per se. If questions or serious concerns remain turn to the parish and if necessary, to the chancery itself. Ask to speak to the Vicar for Religious (or the Vicar for Consecrated Life). S/he will certainly know the person if they are a c 603 (publicly professed solitary) hermit.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:02 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Archdiocese of Seattle, Canon 603, Fraudulent Hermits, importance of lay eremitical vocations, Lay hermits vs diocesan hermits

11 July 2015

Solemnity of St Benedict (Reprise)

Benedict's Rule was a humane development of

Rules already in existence. In it he truly sought to put down "nothing

harsh, nothing burdensome." Today's section of chapter 33 of the Rule of

St Benedict focuses on private possessions. The monk depends entirely

on what the Abbot/Abbess allows (another section of the daily reading

from the Rule makes it clear that the Abbot/Abbess is to make sure their

subjects have what they need!) Everything in the monastery is held in

common, as was the case in the early Church described in Acts. Today, in

a world where consumerism means borrowing from the future of those who

follow us, and robbing the very life of the planet, this lesson is one

we can all benefit from. Benedictine Oblate, Rachel M Srubas reflects on

the necessary attitude we all need to cultivate, living as we do in the

household of God:

UNLEARNING POSSESSION

UNLEARNING POSSESSION

Neither deprivation nor excess,

poverty nor privilege,

in your household.

Even the sheets on "my" bed,

the water flowing from the shower head,

belong to us all and to none of us

but you, who entrust everything to our use.

When I was a toddler,

I seized on the covetous power

of "mine."

But faithfulness requires the slow

unlearning of possession:

to do more than say to a neighbor,

"what's mine is yours."

Remind me what's "mine"

is on loan from you,

and teach me to practice sacred economics:

meeting needs, breaking even, making do.

From, Oblation, Meditations of St Benedict's Rule

My

prayers for and very best wishes to my Sisters and Brothers in the

Benedictine family on this Solemnity of St Benedict! Special greetings

to the Benedictine Sisters at Transfiguration Monastery, the Camaldolese monks at

Incarnation Monastery in Berkeley, and New Camaldoli in Big Sur, the

Trappistine Sisters at Redwoods Monastery in Whitethorn, CA, and all

those at Bishop's Ranch (Healdsburg, CA) who just participated in the

Benedictine Experience Retreat. (It was grand seeing several of you (Catherine and Sister Donald) and some other oblates last week at the Kathleen Norris presentation.) Happy celebrating today and all good wishes for the coming year!

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:02 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Saint Benedict, Solemnity of St Benedict

09 July 2015

On Keeping Things Neat and Tidy

Hi there,

Yes, there is for several reasons. 1) it reflects the contemplative attentiveness and care of the life itself, 2) it reflects the hermit's commitment to poverty, both material poverty and poverty of spirit, 3) it allows for and encourages the sense that it is God and the hermit alone, the relationship between them, that is the real center of things here; there is meant to be little that distracts from this. 4) Moreover, God is present in the ordinary things of life so attentiveness to the ordinary things is also a way of embracing their sacramentality with care and reverence. And 5) the hermit lives "the silence of solitude"; part of the noise she distances herself from is the noise of messiness and clutter and the inner realities which drive us to these.

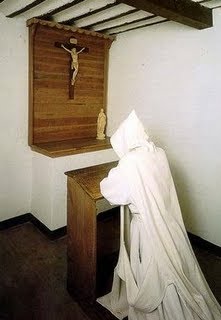

Another reason I should add is 6) hospitality; the hermitage is a place where guests are freely welcomed as Christ and that means it is a sacred space which should be geared to the comfort of someone arriving unexpectedly. If the place is a cluttered mess that becomes much more difficult to do. In a sense this part of tidiness is meant to honor the guest and to provide an environment of quiet and rest she may need badly. Reason 7) has to do with beauty. The hermitage or cell needs to be a place of rest and beauty. It will tend to be a spare beauty as the picture of the Camaldolese chapel above. After all God who is Beauty itself is also supremely simple.

I find that clutter and messiness indicate a kind of unfreedom or even "bondage" within myself. It's always a symptom of falling away from the center somehow. It may mean I am doing too much of one thing (writing, direction) and not enough of another (prayer, cleaning, just relaxing) during a given day, for instance or that my horarium is not really working. It may mean something is bothering me I need to work through. It may mean I am feeling sub par. Clutter tends, in my own life, to indicate a lack of balance and a kind of physical and emotional noisiness or lack of recollectedness. (Of course, when I am really ill things kind of accumulate around the hermitage because I may not have the energy to stay on top of everything so I am not really speaking of those times -- though I guess those are quintessentially times when my life is off balance.)

Most of the time hermitages are pretty spare and free of unnecessary stuff --- unnecessary noise. While a workspace can be messy or cluttered for a given space of time, in general the hermitage really is a place where everything has a definite place with (ideally speaking!) nothing extraneous. It is also a matter of having the time one needs for everything, including taking care of one's environment. Again, a life of prayer is an incredibly orderly life and for most of us clutter occurs when our lives are somehow slackening in terms of prayer, attentiveness, and even a diminishing of peace. In her book, Tools Matter, Meg Funk, OSB speaks of the prayer space or cell as a place where what is not of God can be imaged back to us. In my own life there are some kinds of limited disorder or clutter that mirror creativity and others that are far less edifying, but in general there is no doubt the hermitage or cell is meant to be place which speaks of prayer, rest, peace, and abundant life.

I should note that solitary hermits tend to own more stuff than hermits living in monasteries or lauras simply because we are responsible for our own libraries, prayer spaces, computers (if one uses one), work area, supplies of all sorts, cooking, pantry, etc. Even so, the goal is to have one's living space reflect the eremitical vocation as a contemplative desert vocation centered on God. I should also note that further reading on this can be found in monastic literature under the headings, 'custody of the cell' or 'discipline of the cell.' Thomas Merton has written about this. There is also a good section in Cummings' (OCSO) work, Monastic Practices, and, as noted above, Sister Meg Funk, whose thoughts were influenced by Thomas Merton, has a section on 'the cell' in her book, Tools Matter.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:41 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: neat and tidy, prayer spaces

From Silence to the Silence of Solitude: The Imperceptible Journey

[[Dear Sister, I think of silence as a negative thing; it is something which is the absence of sound or noise. I do understand a little of what you mean when you say it is more than this but only a little. Maybe that's because I have a hard time being really quiet in prayer and when I am quiet I am afraid nothing is happening or that I am experiencing dryness or something. I mean I don't hear anything and I am supposed to be listening for God. I don't feel anything and God is supposed to be there loving me. What am I missing?]]

[[Dear Sister, I think of silence as a negative thing; it is something which is the absence of sound or noise. I do understand a little of what you mean when you say it is more than this but only a little. Maybe that's because I have a hard time being really quiet in prayer and when I am quiet I am afraid nothing is happening or that I am experiencing dryness or something. I mean I don't hear anything and I am supposed to be listening for God. I don't feel anything and God is supposed to be there loving me. What am I missing?]]

Thanks for a great question and especially for sharing what is a pretty intimate experience and concern. First of all I can't really say if you are missing anything, much less what that is, but I can say a little more about the nature of silence in prayer, and especially what I and others call "the silence of solitude". I also want to say something about dryness in prayer and what might be happening to you which would certainly not be dryness.

Our first and more superficial experience of silence is a "negative" thing --- not in the sense of it being without effect or constructiveness, but in the sense of taking or stripping away that which is unhelpful. It involves the quieting of noise, both external and internal, personal noise and the noise of our environment. We each experience this whenever we assure that our prayer space is conducive to prayer; it is part of clearing the space of any clutter, of journaling about the things that are really bothering us or are a matter of concern so that we can close the journal and hand it all over to God when we sit in prayer. It is a matter of stilling our breathing, relaxing our muscles, dropping our defenses and any façade we may hold because of work, etc, and simply bringing ourselves to the moment in an act of self gift and trust.

Already I think it is becoming clear that in prayer we move imperceptibly into the realm of the "positive" dimension here. We move from the things we can more or less do ourselves, the setting of the scene, to the silence which is the work of the Holy Spirit within us ---- as much God's Silence as our own. The quiet act of trust we call faith is one of these. It is an empowered act, not something we can do of ourselves. That is why theologians like Paul Tillich speak about faith as the "state of being grasped. . ." and St Paul speaks of our knowing God but even more properly, of our being known by God. (Remember that Paul does not tease these two apart; he points to the first as a true description and then to the second as even more fundamentally true.) Profound silence is similar. While our descriptions of God often focus on creative speech or word, God is also and simultaneously a transcendent Silence out of which language and all the rest of reality springs; thus we often speak of God as "abyss," ground, or depth dimension --- all of which are most fundamentally matters of a deep but vital and dynamic silence.

Already I think it is becoming clear that in prayer we move imperceptibly into the realm of the "positive" dimension here. We move from the things we can more or less do ourselves, the setting of the scene, to the silence which is the work of the Holy Spirit within us ---- as much God's Silence as our own. The quiet act of trust we call faith is one of these. It is an empowered act, not something we can do of ourselves. That is why theologians like Paul Tillich speak about faith as the "state of being grasped. . ." and St Paul speaks of our knowing God but even more properly, of our being known by God. (Remember that Paul does not tease these two apart; he points to the first as a true description and then to the second as even more fundamentally true.) Profound silence is similar. While our descriptions of God often focus on creative speech or word, God is also and simultaneously a transcendent Silence out of which language and all the rest of reality springs; thus we often speak of God as "abyss," ground, or depth dimension --- all of which are most fundamentally matters of a deep but vital and dynamic silence.

In prayer what happens beyond the "negative" work of coming to relative silence we all recognize as our own work is that we are taken hold of by the profound Silence which is God. When this happens it is hard or even impossible to tease apart the silence we "achieve" and the silence that is "achieved" in us. It is at these times we know the communion with God and the whole of God's creation which is most clearly and profoundly what we call the silence of solitude . You may remember that I wrote, [[. . . the silence of solitude refers to what is created within the hermit, or better put perhaps, it refers to the person . . . who is created by the dialogue with God in the hermitage. This is what I referred to when I spoke of shalom, or the wholeness, peace, and joy that is the fruit of an eremitical life. Much of the "noisiness" of human yearning and exertion is silenced; so is the scream of self-centeredness and the inability to listen to or hear others. One is at peace with God and with oneself; one is at home with God wherever one goes.]] All of this happens in prayer and is carried through the rest of the pray-er's life.

It is the Silence of God that stills our human yearnings and striving. It is the Silence of God that meets our own tentative and struggling attempts at quiet and completes them. It is the loving, embracing, silence of God that takes hold of us in prayer, soothes our stammerings and quiets our cries of anguish and emptiness. But it does so much more than this as well. God's own Silence is the silence that holds all things together in a way which makes sense of them; it is the all-embracing quies which makes music of the individual notes and rhythms of our lives and world. It is the deepest reality out of which all creation comes and all reconciliation is achieved, the hesychia in which everything truly belongs and is one. When and to the extent the Silence of God grasps us we become God's own prayers in our world, articulate words reflecting God's life and meaning, magnificats which are the transfigured stammerings of the journey from isolation and absurdity to genuine solitude and song. There is a reason Mary is sometimes called "a woman wrapped in silence"; only part of that has to do with her struggle and pain and inability to express what she knows and ponders in her own heart. The greater part has to do with the embrace of God which holds and makes sense of all things.

It is the Silence of God that stills our human yearnings and striving. It is the Silence of God that meets our own tentative and struggling attempts at quiet and completes them. It is the loving, embracing, silence of God that takes hold of us in prayer, soothes our stammerings and quiets our cries of anguish and emptiness. But it does so much more than this as well. God's own Silence is the silence that holds all things together in a way which makes sense of them; it is the all-embracing quies which makes music of the individual notes and rhythms of our lives and world. It is the deepest reality out of which all creation comes and all reconciliation is achieved, the hesychia in which everything truly belongs and is one. When and to the extent the Silence of God grasps us we become God's own prayers in our world, articulate words reflecting God's life and meaning, magnificats which are the transfigured stammerings of the journey from isolation and absurdity to genuine solitude and song. There is a reason Mary is sometimes called "a woman wrapped in silence"; only part of that has to do with her struggle and pain and inability to express what she knows and ponders in her own heart. The greater part has to do with the embrace of God which holds and makes sense of all things.

I think sometimes what people mistakenly call dryness is this incredible Silence. Maybe real dryness also means resisting this silence, fearing it and refusing to entrust ourselves to it, refusing to let it take hold of us or resisting resting in it even though we also yearn for it. Personally I know that I rarely feel dryness in prayer simply because I am not hearing or sensing anything. God is present and at work --- loving, calling, touching, healing, creating --- all the things God is and does in and as profound silence. I know and trust that. More, I know Silence as the Divine reality that can and does comprehend me even as it resides and sings within me. What I am encouraging you to do is to trust this Silence, this kind of no-thing, this abyss which is actually the fullness of God --- a fullness far too "big" (such an inadequate word!) to even perceive sometimes --- and don't label what happens in prayer as "dryness" quite so quickly or easily as you might otherwise do. From my experience I would say that what we are "listening for" is this transcendent and mysterious Silence. The love we are hoping to feel is actually an experience of this profound quies and sense of being encompassed and contextualized, the experience of being comprehended in every sense of that word by the Silence which is God.

As a kind of postscript, let me say that it is this Silence I think e. e. cummings knew when he wrote the wonderful poem I have had in the side bar of my blog since the day of my profession.

love is a place

& in this place of

love move

(with brightness of peace)

all places

yes is a world

& in this world of

yes live

(skillfully curled)

all worlds

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

3:04 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: abyss, e e cummings, Faith and being grasped by beauty, love is a place, Prayer, silence of solitude

08 July 2015

Replying to Objections and Misunderstandings

Thanks for your email. Yes, I saw the post (or posts) several months ago. I have written about all of these assertions in one way and another here so it did not seem necessary to respond, but since you ask, and since the post is actually being read perhaps I do need to cite and respond to the assertions in a more direct way. Maybe all these points need to be present in a single post I can simply link people to in the future. (While I do welcome all questions and will continue to do so, that would be a relief from having to write the same stuff yet again!) In any case, let me be clear that, as far as I am aware, none of these points is a matter of interpretation on which reasonable folks may differ. The assertions made by the poster cited seem to me to be rooted in misunderstanding or actual ignorance of language and usage many of us, myself included, take for granted. Probably we ought not do that. In any case, I have broken up the post you have supplied and answered each point below. I sincerely hope this is helpful.

[[There is no mention of the hermit having a "Superior" in either The Catechism of the Catholic Church or in Canon Law 603. The latter does state that the hermit who publicly professes the three evangelical counsels into the hands of the diocesan bishop, is to live his or her proper program of living under the diocesan bishop's direction. Thus, the hermit's director is by [church] law to be his or her bishop.]]

When a canon says that one makes their public profession in the hands of another (for instance, the local ordinary or diocesan Bishop) they are identifying that person as the legitimate superior of the one making their profession. As noted in other posts, the act of making one's profession in the hands of another harks back to feudal times when folks made acts of fealty in the hands of their political and legitimate superiors. Today there is a clear sense of intimacy about this act because it establishes a legal or legitimate relationship (and a moral one as well) in which the two people entrust themselves to this relationship -- though in very different ways -- so that a God-given vocation can flourish.

The meaning of this act was immeasurably enriched and made clearer to me when I first met with Archbishop Vigneron on the Feast of the Sacred Heart. At the end of that meeting he extended his hands and I rested mine in his while we both prayed for the process of discernment we were embarking on together. Later, when I made my vows in his hands while resting them on the book of Gospels, I recalled that first meeting and time with others where prayer was linked to resting my hands in theirs. It was especially poignant because of this. These relationships have been life giving to me and a source of the mediation of my vocation.

The bottom line here is that the actual words "legitimate superior" are not necessary. The concept is clearly present throughout. Canon 603 refers to public profession, to being recognized in law and to making one's profession in the hands of the local Bishop under whose direction the hermit will live her life. All of these imply or explicitly refer to the reality of legitimate superiors. Direction, for instance, does not mean spiritual direction (as in the work of a spiritual director per se --- even if that person is the bishop!) but rather is the general term for the exercise of authority by a legitimate superior. Meanwhile, the obedience owed one's legitimate superior differs in character from the general obedience one owes one's spiritual director, Scripture, one's pastor, et al. and this is clearly referred to via the presence of references to canon law and a personal Rule, Plan, or Program of Life.

As I wrote a while back, if one wonders if a hermit is legitimate (canonical), that is, if she is canonically commissioned to live her life in the name of the Church then ask her who her legitimate superior is. That works for any religious one is doubtful of as well. In a solitary hermit's case this will ALWAYS be the local diocesan bishop.

[[Rule of Life: Again, adopting an individual rule of life is not stipulated per se in the institutes of the Catholic Church or CL603 per the consecrated eremitic life. However, history and tradition of eremites who successfully and heroically lived a holy hermit life, as well as prudence and wisdom, suggest that determining and being true to a rule of life is a positive inclusion.]] and also [[ Can. 603 §1. In addition to the institutes of consecrated life, the Church recognizes the eremitic or anchoritic life by which the Christian faithful devote their life to the praise of God and the salvation of the world through a stricter withdrawal from the world, the silence of solitude, and assiduous prayer and penance.]]

The phrase "institutes of the Catholic Church" as some sort of law or statutes is not recognized usage. In any case, Canon 603 does not read "the institutes". Instead it says, "besides institutes of consecrated life canon law also recognizes the eremitic or anchoritic life" and by this it means, "Besides congregations, Orders, and communities of consecrated life canon law (the Church) also recognizes solitary consecrated eremitical life" and does so specifically in this canon. This portion of the canon outlines c 603 as the single recognized way to public profession for hermits who are not part of institutes of consecrated life. Regarding the assertion that a Rule is not an explicit requirement of canon 603, the canon also reads, "and observes his or her plan of life (vivendi rationem) in (the Bishop's) hands." The plan of life is ordinarily written out and approved by the Bishop. (The approval is formalized in a Bishop's decree of approval.) Sometimes it is called a Rule or "regula" or even Rule or Program of Life but what is really clear is that the canon specifies such a Rule or Plan.