[[Could you write something about today's feast of the Exaltation of the Cross? What is a truly healthy and yet deeply spiritual way to exalt the Cross in our personal lives, and in the world at large (that is, supporting those bearing their crosses while not supporting the evil that often causes the destruction and pain that our brothers and sisters are called to endure due to sinful social structures?]]

The above question which arrived by email was the result of reading some of my posts, mainly those on victim soul theology, the Pauline theology of the Cross, and some earlier ones having to do with the permissive will of God. For that reason my answer presupposes much of what I wrote in those and I will try not to be too repetitive. First of all, in answering the question, I think it is helpful to remember the alternative name of this feast, namely, the Triumph of the Cross. For me personally this is a "better" name, and yet, it is a deeply paradoxical one, just like its alternative.

(Crucifix in Ambo of Cathedral of Christ the Light; Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, or Cathedral Sunday in the Diocese of Oakland)

How many times have we heard it suggested that Christians ought not wear crosses around their necks as jewelry any more than they should wear tiny images of electric chairs, medieval racks or other symbols of torture and death? Similarly, how many times has it been said that making jewelry of the cross trivializes what happened there? There is a great deal of truth in these objections, and in similar ones! On the one hand the cross points to the slaughter by torture of hundreds of thousands of people by an oppressive state. More individually it points to the slaughter by torture of an innocent man in order to appease a rowdy religious crowd by an individual of troubled but dishonest conscience, one who put "the supposed greater good" before the innocence of this single victim.

And of course there were collaborators in this slaughter: the religious establishment, disciples who were either too cowardly to stand up for their beliefs, or those who actively betrayed this man who had loved them and called them to a life of greater abundance (and personal risk) than they had ever known before. If we are going to appreciate the triumph of the cross, if we are going to exalt it as Christians do and should, then we cannot forget this aspect of it. Especially we cannot forget that much that happened here was NOT THE WILL OF GOD, nor that generally the perpetrators were not cooperating with that will! The cross was the triumph of God over sin and sinful godless death, but it was ALSO a sinful and godless human (and societal!) act of murder by torture. (In fact one could argue it was a true divine triumph ONLY because it was also these all-too-human things.) Both aspects exist in tension with each other, as they do in ALL of God's victories in our world. It is this tension our jewelry and other crucifixes embody: they image miniature instruments of torture, yes, but they are also symbols of God's ultimate triumph over the powers of sin and death with which humans are so intimately entangled and complicit. Today's first reading prepares us for this paradox with its serpent lifted up on a staff; today we recognize not a symbol of poisoning and death but the caduceus, a symbol of medical care, comfort, and healing.

In our own lives there are crosses, burdens which are the result of societal and personal sin which we must bear responsibly and creatively. That means not only that we cannot shirk them, but also that we bear them with all the asistance that God puts into our hands. Especially it means allowing God to assist us in the carrying of this cross. To really exalt the cross of Christ is to honor all that God did with and made of the very worst that human beings could do to another human being. To exult in our own personal crosses means, at the very least, to allow God to transform them with his presence. That is the way we truly exalt the Cross: we allow it to become the way in which God enters our lives, the passion that breaks us open, makes us completely vulnerable, and urges us to embrace or let God embrace us in a way which comforts, sustains, and even transfigures the whole face of our lives.

If we are able to do this, then the Cross does indeed triumph. Suffering does not. Pain does not. Neither will our lives be defined in terms of these things despite their very real presence. What I think needs to be especially clear is that the exaltation of the cross has to do with what was made possible in light of the combination of awful and humanly engineered torment, and the grace of God. Sin abounded but grace abounded all the more. Does this mean we invite suffering so that "grace may abound all the more?" Well, Paul's clear answer to that question was, "By no means!" How about tolerating suffering when we can do something about it? What about remaining in an abusive relationship, or refusing medical treatment which would ease mental and physical pain, for instance? Do we treat these as crosses we MUST bear? Do we allow ourselves to become complicit in the abuse or the destructive effects of pain and physical or mental illness? I think the general answer is no, of course not.

That means we must look for ways to allow God's grace to triumph, while the triumph of grace ALWAYS results in greater human freedom and authentic functioning. Discerning what is necessary and what will REALLY be an exaltation of the cross in our own lives means determining and acting on the ways freedom from bondage and more authentic humanity can be achieved. Ordinarily this will mean medical treatment; or it will mean moving out of the abusive situation. In ALL cases it means remaining open to and dependent upon God and to what he desires for our lives IN SPITE of the limitations and suffering inherent in them. This is what Jesus did, and what made his cross salvific. This openness and responsiveness to God and what he will do with our lives is, as I have said many times before, what the Scriptures called obedience. Let me be clear: the will of God in ANY situation is that we remain open to him and that authentic humanity be achieved. We MUST do whatever it is that allows us to not close off to God, and to remain open to growth AS HUMAN. If our pain dehumanizes, then we must act in ways which changes that. If our lives cease to reflect the grace of God (and this means fails to be a joyfilled, free, fruitful, loving, genuinely human life) then we must act in ways which change that.

The same is true in society more generally. We must act in ways which open others TO THE GRACE OF GOD. Yes, suffering does this, but this hardly means we simply tell people to pray, grin, and bear it ---- much less allow the oppressive structures to stay in place! As the gospels tell us, "the poor you will always have with you" but this hardly means doing nothing to relieve poverty! Similarly we will always have suffering with us on this side of death, and especially the suffering that comes when human beings institutionalize their own sinful drives and actions. What is essential is that the Cross of Christ is exalted, that the Cross of Christ triumphs in our lives and society, not simply that individual crosses remain or that we exalt them (especially when they are the result of human engineering and sin)! And, as I have written before, to allow Christ's Cross to triumph is to allow the grace of God to transform all the dark and meaningless places with his presence, light and love. It is ONLY in this way that we truly "make up for what is lacking in the passion of Christ."

The paradox in today's Feast is that the exaltation of the Cross implies suffering, and stresses that the cross empowers the ability to suffer well, but at the same time points to a freedom the world cannot grant --- a freedom in which we both transcend and transform suffering because of a victory Christ has won over the powers of sin and death which are built right into our lives and in the structures of this world. Thus, we cannot ever collude with the powers of this world; we must always be sure we are acting in complicity with the grace of God instead. Sometimes this means accepting the suffering that comes our way (or encouraging and supporting others in doing so of course), but never for its own sake. If our (or their) suffering does not result in greater human authenticity, greater freedom from bondage, greater joy and true peace, then it is not suffering which exalts the Cross of Christ. If it does not in some way transform and subvert the structures of this world which oppress and destroy, -then it does not express the triumph of Jesus' Cross, nor are we really participating in THAT Cross in embracing our own.

I am certain I have not completely answered your question, but for now this will need to suffice. My thanks for your patience. If you have other questions which can assist me to do a better job, I would very much appreciate them. Again, thanks for your emails.

14 September 2018

Questions on Suffering and the Exaltation of the Cross (Reprise)

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

4:53 AM

![]()

![]()

12 September 2018

The Silence of Solitude, a Share in the Abyss of God's own Heart

[[Hi Sister, I wondered why you speak of solitude in personified terms. You say "she herself must open the door to the hermit". Do you think of solitude as a living thing?]]

Thanks for the question. I have repeated Thomas Merton's observation that one cannot choose solitude as one's own vocation; solitude must open the door to the hermit or there is no vocation. I can't say why Merton used this personification with real certainty, but I know that it reminds me of references to Wisdom in the OT, where Wisdom or Sophia, is a dimension of God --- and a distinctly feminine one at that! I suspect that this same sense might have been true for Merton. In describing the Eremo which is the Motherhouse of the OSB Camaldolese in Tuscany, Merton writes: [[In order to seek Him who is inaccessible the hermit himself becomes inaccessible. But within the little village of cells centered about the Church of the Eremo is a yet more perfect solitude: that of each hermit's own cell. Within the cell is the hermit (himself), in the solitude of his own soul. But --- and this is the ultimate test of solitude --- the hermit is not alone with himself: for that would not be sacred loneliness. Holiness is life. Holy Solitude is nourished with the Bread of Life and drinks deep at the very Fountain of all Life. The solitude of the soul enclosed within itself is death. And so, the authentic, the really sacred solitude is the infinite solitude of God Himself, Alone, in Whom the hermits are alone,]] (Disputed Questions, A Renaissance Hermit, p. 169)

Thanks for the question. I have repeated Thomas Merton's observation that one cannot choose solitude as one's own vocation; solitude must open the door to the hermit or there is no vocation. I can't say why Merton used this personification with real certainty, but I know that it reminds me of references to Wisdom in the OT, where Wisdom or Sophia, is a dimension of God --- and a distinctly feminine one at that! I suspect that this same sense might have been true for Merton. In describing the Eremo which is the Motherhouse of the OSB Camaldolese in Tuscany, Merton writes: [[In order to seek Him who is inaccessible the hermit himself becomes inaccessible. But within the little village of cells centered about the Church of the Eremo is a yet more perfect solitude: that of each hermit's own cell. Within the cell is the hermit (himself), in the solitude of his own soul. But --- and this is the ultimate test of solitude --- the hermit is not alone with himself: for that would not be sacred loneliness. Holiness is life. Holy Solitude is nourished with the Bread of Life and drinks deep at the very Fountain of all Life. The solitude of the soul enclosed within itself is death. And so, the authentic, the really sacred solitude is the infinite solitude of God Himself, Alone, in Whom the hermits are alone,]] (Disputed Questions, A Renaissance Hermit, p. 169)

What Merton is getting at, I think, is that eremitical solitude is not only lived in communion with God, but it is communion with God lived within the very life of God. It is of itself a dimension of the God who exists both as a community of love and as an abyss of solitude. It is the life of God which is opened to us when solitude opens her door to us. Cornelius Wencel, Er Cam, says something very similar in speaking of two freedoms meeting one another in The Eremitic Life. He writers: [[In this sense the eremitic calling is a consequence of meeting the original depths of the Trinity's solitude. God is the living interpersonal relationship of love inasmuch as he is the presence of the original abyss of solitude and silence. The reality of God is thus the original source of any solitude, an impenetrable abyss that calls to the profound depths of solitude of the human heart. Having heard that existential call of God's solitude, people respond to it by opening up the whole secret of their hearts.]]

So, yes, I personify Solitude because I understand it as a dimension, even the most fundamental dimension of God's own heart. To speak of Solitude opening the door to us is to speak of God opening a particular dimension of God's own heart to us and inviting us to dwell there in silence and solitude and coming to the human wholeness, holiness, and rest hermits call "the silence of solitude" and hesychasts call "quies". It is critically important that we understand how qualitatively different from ("mere") silence and solitude is the reality we call "the silence of solitude" or "eremitical solitude". The first is simply the (still important!) absence of sound and others; the latter is life lived in the solitary abyss of God's heart and so, a living and communal reality. This is also the reason I identify the Silence of Solitude not only as environment, but also as goal, and charism of the eremitical life.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

3:29 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: abyss, the Silence of Solitude

Questions on "Justifying" Inner Work

[[Dear Sister O'Neal, when you write about the inner work you have undertaken you justify it in the name of your vocation --- as though your vocation itself called for it and made it the right and necessary thing to do. I wonder if that is really true. I don't think I have read about any other hermit undertaking this kind of work after leaving the world or entering the desert! It seems entirely unique to you. Do you really think other hermits might be called to this kind of "work" or could you be justifying it in order to remain a hermit?]]

[[Dear Sister O'Neal, when you write about the inner work you have undertaken you justify it in the name of your vocation --- as though your vocation itself called for it and made it the right and necessary thing to do. I wonder if that is really true. I don't think I have read about any other hermit undertaking this kind of work after leaving the world or entering the desert! It seems entirely unique to you. Do you really think other hermits might be called to this kind of "work" or could you be justifying it in order to remain a hermit?]]

Thanks for your questions! They do push me further in writing about this work. First, I have no idea how many other hermits are acquainted with PRH; I know that Father Michael Fish, OSB Cam has done PRH and knows my director/accompanist personally for her skills in PRH, but beyond Michael's experience I don't know of other hermits who have engaged in this work. At the same time I think it is important to remember the entire history of eremitical life and the frequent references that occur throughout this history to the struggle or outright battle with demons --- most of which, I am sure, are the demons of our own hearts. As I wrote here a couple of years ago in On Battling Demons and Mediating Peace:

[[. . .believe me, when we deal with the parts of ourselves left unhealed, distorted, or broken in childhood and throughout life, the process of healing can be as fierce, demanding, and messy as stories of Desert ancestors battling all day and night long with demons then coming out of their caves torn and bloodied but exultant in the morning! The same is true of the story of Jacob wrestling with God (God's angel) and, painfully wounded though he was, refusing to let go until God blessed him. We enter the desert both to seek God and to do battle with demons; it is a naïve person indeed who does not anticipate meeting herself face to face there in all of her weakness, brokenness, and [(fortunately), her] giftedness as well! We may well know that God is profoundly involved in what may eventuate into the fight/struggle of and for our lives but it can take time, faith, and perseverance before we walk away both limping and blessed beyond measure.]] (cf Sources and Resources for Inner Work)

I am also reminded of a passage from Thomas Merton's Disputed Questions in the essay "The Renaissance Hermit"; here Merton cites Bl. Paul Giustiniani: [[It is here, in this inexpressible rending of his own poverty, that the hermit enters, like Christ, into an arena where (she) wages the combat that can never be told to anyone. This is the battle that is seen by no one except God, and whose vicissitudes are so terrible that when victory comes at last, the total poverty and emptiness of the victor are so absolute that there is no longer any place in (her) heart for pride.]]

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:13 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Demons --- battling with, inner work, Michael Fish OSB Cam, Paul Giustiniani, PRH, Struggling with Demons

10 September 2018

What are Signal Graces?

[[Dear Sister Laurel, can you tell me what a "signal grace" is? Does it mean God is sending us a "signal" like an image of Jesus pointing the way or causing a bell to ring or something? Thank you.]]

Sure. A signal grace is a grace which is exceptional and stands as the "originating grace" for many others. Thus, for instance, in my own life the chance to attend Mass with a high school friend was a signal grace which led to my first vision of what the Church is as well as to my catechesis, baptism, and conversion. The opportunity to study theology under John Dwyer was not simply a grace, but a signal grace which became the source and even foundation for many, many other graces --- not least my love for Scripture or the ability to reflect theologically on things (like c 603!), and especially Paul's theology of the cross -- which has allowed me to live my entire adult life in light of God's promise of new life. The prayer experience I have described here which occurred @ 1982 at the prompting/invitation of my director was a signal grace as was my director's consent to act as my delegate with and for the Diocese of Oakland. My stumbling across canon 603 in 1983-84 while checking out the Revised Code of Canon Law was a signal grace which led me to eremitical life and all the graces that have come from this --- not least the recent work I have undertaken with the assistance/accompaniment of my director or some work I am currently doing re canon 603 itself. And finally, of course, eremitical profession itself has been a signal grace along this same stream of graces for which I thank God daily.

Sure. A signal grace is a grace which is exceptional and stands as the "originating grace" for many others. Thus, for instance, in my own life the chance to attend Mass with a high school friend was a signal grace which led to my first vision of what the Church is as well as to my catechesis, baptism, and conversion. The opportunity to study theology under John Dwyer was not simply a grace, but a signal grace which became the source and even foundation for many, many other graces --- not least my love for Scripture or the ability to reflect theologically on things (like c 603!), and especially Paul's theology of the cross -- which has allowed me to live my entire adult life in light of God's promise of new life. The prayer experience I have described here which occurred @ 1982 at the prompting/invitation of my director was a signal grace as was my director's consent to act as my delegate with and for the Diocese of Oakland. My stumbling across canon 603 in 1983-84 while checking out the Revised Code of Canon Law was a signal grace which led me to eremitical life and all the graces that have come from this --- not least the recent work I have undertaken with the assistance/accompaniment of my director or some work I am currently doing re canon 603 itself. And finally, of course, eremitical profession itself has been a signal grace along this same stream of graces for which I thank God daily.

Signal graces are not usually actual signals like a vision of Jesus literally pointing to a door or causing a bell to ring as a signal to us. (Though if either of these were to happen to us they could also be signal graces in the accepted sense used in this post. Merton, for instance, once had a dream in which he heard the bell of the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani; that dream was a signal grace for him, possibly in both senses.) In this post's (and ordinary) usage, however, "signal" is an adjective meaning notable, as in a signal event or achievement. Theologically we extend this definition and see it as an "originating" grace. Given this meaning we look back at the stand-out graces in our lives, the really pivotal graces that represent a kind of turning point leading to innumerable other graces we might otherwise never have known. Each of the graces I mentioned above represented a turning point, a grace in light of which I and my life would never be the same. Each led to further graces (further experiences of the powerful presence of God), and a kind of fruitfulness that can only be described in hindsight. (We might or might not know a grace is significant at the moment it occurs, but signal graces are recognized in hindsight as we look at the subsequent pattern of graces associated with or originating from them.)

Signal graces are not usually actual signals like a vision of Jesus literally pointing to a door or causing a bell to ring as a signal to us. (Though if either of these were to happen to us they could also be signal graces in the accepted sense used in this post. Merton, for instance, once had a dream in which he heard the bell of the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani; that dream was a signal grace for him, possibly in both senses.) In this post's (and ordinary) usage, however, "signal" is an adjective meaning notable, as in a signal event or achievement. Theologically we extend this definition and see it as an "originating" grace. Given this meaning we look back at the stand-out graces in our lives, the really pivotal graces that represent a kind of turning point leading to innumerable other graces we might otherwise never have known. Each of the graces I mentioned above represented a turning point, a grace in light of which I and my life would never be the same. Each led to further graces (further experiences of the powerful presence of God), and a kind of fruitfulness that can only be described in hindsight. (We might or might not know a grace is significant at the moment it occurs, but signal graces are recognized in hindsight as we look at the subsequent pattern of graces associated with or originating from them.)

I hope this is helpful.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

12:27 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: signal graces

09 September 2018

Healing of the Deaf, Speech-Impaired Man (Reprise)

Today's Gospel brought us face to face with who we are called to be, and with the results of the idolatry that occurs whenever we refuse that vocation. Both issues, vocation and true worship are rooted in the Scriptural notion of obedience, that is in the obligation which is our very nature, to hearken --- to listen and respond to God appropriately with our whole selves. When we are empowered to and respond with such obedience our very lives proclaim the Kingdom of God, not as some distant reality we are still merely waiting for, but as something at work in us here and now. In fact, when our lives are marked by this profound dynamic of obedience, today's readings remind us the reign of God cannot be hidden from others --- though its presence will be seen only with the eyes of faith.

Today's Gospel brought us face to face with who we are called to be, and with the results of the idolatry that occurs whenever we refuse that vocation. Both issues, vocation and true worship are rooted in the Scriptural notion of obedience, that is in the obligation which is our very nature, to hearken --- to listen and respond to God appropriately with our whole selves. When we are empowered to and respond with such obedience our very lives proclaim the Kingdom of God, not as some distant reality we are still merely waiting for, but as something at work in us here and now. In fact, when our lives are marked by this profound dynamic of obedience, today's readings remind us the reign of God cannot be hidden from others --- though its presence will be seen only with the eyes of faith.

In the Gospel, (Mark 7:31-37) A man who is deaf and also has a resultant speech impediment is brought by friends to Jesus; Jesus is begged to heal him. In what is an unusual process for Mark (or for any of the Gospel writers) in its crude physicality, Jesus puts his fingers in the man's ears, and then, spitting on his fingers, touches the man's tongue. He looks up to heaven, groans, and says in Aramaic, "ephphatha!" (that is, "Be opened!"). Immediately the man is healed and "speaks plainly." Those who brought him to Jesus are astonished, joyful, and could not contain their need to proclaim Jesus and what he had done: "He has done all things well. He makes the deaf hear and the mute speak."

I am convinced that the deaf and "mute" man (for he is not really mute, but impeded from clear speech by his inability to hear) is a type of each of us, a symbol for the persons we are and for the vocation we are each called to. Theologians speak of human beings as "language events." We are called to be by God, conceived from and an expression of the love of two people for one another, named so that we have the capacity for personal presence in the world and may be personally addressed by others; we are shaped for good or ill, for wholeness or woundedness, by every word which is addressed to us. Language is the means and symbol of our capacity for relationship and transcendence.

Consider how it is that vocabulary of all sorts opens various worlds to us and makes the whole of the cosmos our own to understand, wonder at, and render more or less articulate; consider how a lack of vocabulary whether affective, theological, scientific, mathematical, musical, psychological, etc, can cripple us and distance us from effectively relating to various dimensions of human life including our own heart. Note, for instance that physicians have found that in any form of mental illness there is a corresponding dimension of difficulty with or dysfunction of language. Consider the very young child's wonderful (and often really annoying!) incessant questioning. There, with every single question and answer, language mediates transcendence (a veritable explosion of transcendence in fact!) and initiates the child further and further into the world of human community, knowledge, understanding, reflection, celebration, and commitment. Language marks us as essentially communal, fundamentally dependent upon others to call us beyond ourselves, essentially temporal AND transcendent, and, by virtue of our being imago dei, responsive and responsible (obedient) at the core of our existence.

One theologian (Gerhard Ebeling), in fact, notes that the most truly human thing about us is our addressiblity and our ability to address others. Addressibility includes and empowers responsiveness; that is, it has both receptive and expressive dimensions. It is the characteristically human form of language which creates community. It marks us as those whose coming to be is dependent upon the dynamic of obedience --- but also on the generosity of those who would address us and give us a place to stand as persons --- places we cannot assume on our own. We spend our lives responsively -- coming (and often struggling) to attend to and embody or express more fully the deepest potentials within us in myriad ways and means and doing so as an answer to the invitation of God's very personal call and other's love for us.

But a lot can hinder this most foundational vocational accomplishment. Sometimes our own woundedness prevents the achievement of this goal to greater degrees. Sometimes we are not given the tools or education we need to develop this capacity. Sometimes, we are badly or ineffectually loved and rendered relatively deaf and "mute" in the process. Oftentimes we muddle the clarity of that expression through cowardice, ignorance, or even willful disregard. Our hearts, as I have noted here before, are dialogical realities. That is, they are the place where God bears witness to himself, the event marked in a defining way by God's continuing and creative address and our own embodied response. In every way our lives are either an expression of the Word or logos of God which glorifies (him), or they are, to whatever extent, a dishonoring evasion, distortion, or even an outright lie.

And so, faced with a man who is crippled in so many fundamental ways --- one, that is, for whom the world of community, knowledge, and celebration is largely closed by disability, Jesus prays to God, touches, and addresses the man directly, "Ephphatha!" ---Be thou opened!" It is the essence of what Christians refer to as salvation, the event in which a word of command and power heals the brokennesses which cripple and isolate, and which, by empowering obedience reconciles the man to himself, his God, his people and world. As a result of Jesus' Word, and in response, the man speaks plainly --- for the first time (potentially) transparent to himself and to those who know him; he is more truly a revelatory or language event, authentically human and capable through the grace of God of bringing others to the same humanity through direct response and address.

And so, faced with a man who is crippled in so many fundamental ways --- one, that is, for whom the world of community, knowledge, and celebration is largely closed by disability, Jesus prays to God, touches, and addresses the man directly, "Ephphatha!" ---Be thou opened!" It is the essence of what Christians refer to as salvation, the event in which a word of command and power heals the brokennesses which cripple and isolate, and which, by empowering obedience reconciles the man to himself, his God, his people and world. As a result of Jesus' Word, and in response, the man speaks plainly --- for the first time (potentially) transparent to himself and to those who know him; he is more truly a revelatory or language event, authentically human and capable through the grace of God of bringing others to the same humanity through direct response and address.

Our own coming to wholeness, to a full and clear articulation of our truest selves is a communal achievement. Even (or even especially) in the lives of hermits this has always been true insofar as solitude is NOT isolation but is instead a form of communion marked by profound dependence on the Word of God and lived specifically for the salvation of others. In today's gospel friends bring the man to Jesus, Jesus prays to God before acting to heal him. The presence of friends is another sign not only of the man's nature as made-for-communion and the fact that none of us come to language (or, that is, to the essentially human capacity for responsiveness or obedience) alone, but similarly, of the deaf man's total inability to approach Jesus on his own. At the same time, Jesus takes the man aside and what happens to him in this encounter is thus signaled to be profoundly personal, intimate, and beyond the merely-evident. Friends are necessary, but at bottom, the ultimate healing and humanizing encounter can only happen between the deaf man and Christ.

In each of our lives there is deafness and "muteness" or inarticulateness. So many things are unheard by us, fail to touch or resonate in our hearts. So many things call forth embittered and cynical reactions which wound and isolate when what is needed is a response of genuine compassion and welcoming. Similarly, so many things render us speechless or relatively inarticulate as we hold ourselves apart and defended: bereavement, illness, ignorance, personal woundedness, etc. As a result we live our commitments half-heartedly, our loves guardedly, our joys tentatively, our pains self-consciously and noisily --- but helplessly and without meaning in ways which do not edify --- and in all these ways therefore, we are less human, less articulate, less the obedient or responsive language event we are called to be. To each of us, then, and in whatever way or degree we need, Jesus says, "EPHPHATHA!" "Be thou opened!" He sighs in compassion and desire, unites himself with his Father in the power of the Holy Spirit, and touches us with his own hands and spittle.

May we each allow ourselves to be brought to Jesus for healing. May we be broken open and rendered responsive and transparent by his powerful Word of command and authority. Especially, may we each become the clear gospel-founded words of joy and hope in a world marked extensively and profoundly by deafness and the helplessness and the despair of noisy inarticulateness.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

2:00 PM

![]()

![]()

05 September 2018

What Would You Have Done IF. . .?????

[[Dear Sister, thank you for your post on the work you undertook 2 years ago or so. I wondered what you would have done had you discerned eremitical solitude was not something you were still called to? Probably that is difficult to answer but was this something you thought about?]]

[[Dear Sister, thank you for your post on the work you undertook 2 years ago or so. I wondered what you would have done had you discerned eremitical solitude was not something you were still called to? Probably that is difficult to answer but was this something you thought about?]]

Great question! And yes, it is certainly a difficult one to answer because I would only be considering what might have been. What I did think about was not so much what would change as what would remain the same. After all, certain truths, certain personal gifts, skills, inclinations, and obligations would remain whether I remained a hermit or not. I would still be a theologian, still be pastoral assistant at my parish; I would still be involved in the lives of clients as spiritual director, still be committed to writing about c 603, c 604 (perhaps), still be a writer and musician, and so forth. If I were ever to leave my vows/eremitical life, I would no longer be publicly vowed but I would remain bound by the evangelical counsels probably by private vows. My commitment to a life of prayer, to the work I have undertaken with the assistance of my director would remain -- and substantial parts of these would remain entirely unchanged.

However, some things might change, especially in terms of ministry. For instance, I would like to do more pastoral ministry in my parish --- though my not doing so is not solely a matter of being constrained by eremitical solitude. Still, this would be the first thing I would consider. Something that could dovetail with this is teaching. Again, to some degree I am allowed to do this even as a hermit but to a much more limited degree than I would if I left eremitical life. Unfortunately, there are other significant constraints on my life --- chronic illness with a medically and surgically intractable seizure disorder and chronic pain (complex regional pain syndrome) --- and these would still need to be dealt with as they are today. I have no doubt, however, that folks would help me in negotiating a wider world in terms of new or expanded work if that were to open up to me. It would be a learning situation for sure but what I know is, whatever I determined to undertake, I would not be doing it alone any more than I live eremitical life entirely alone.

So, my basic answer is my life would look a lot like it does today; it would involve the same gifts and activities with some broadening and expansion of things I have done (or considered doing) in the past. One thing I would definitely be doing, however, if I ceased to be a hermit, is spending more time with friends --- and whether I did these things with them or alone I would be seeing more movies, going to more museums, lectures, and concerts, and just getting out and about more (maybe on my new electric bike (!!!) but also on our local/regional transit system).

A note on the picture above: during our first year of work together, as part of a response to that same work I recovered some "lost gifts" and means of expression. One of these was drawing. Thus, I drew a picture of myself coloring/drawing because I saw myself (through the grace of God) slowly creating an entire universe "page by page" (not to mention tapping into the deepest places within myself in the process). It was a picture in which the individual pages often looked little different from one another and which took shape bit by bit; it was huger than I could ever capture on paper of course, but so we continued, step by step.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

6:21 PM

![]()

![]()

Does God Send or Choose Suffering for Us?

[[Dear Sister Laurel, do you believe God chose for you to experience the trauma you wrote about yesterday? Some people affirm that God chooses the pain they experience or the difficulties they have. I understand how that seems to make sense of things for them but for me it makes God something of a sadist. Maybe that's a bit strong but I think you know what I mean. Anyhow, do you think God chose the trauma you referred to so that you would become a hermit?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, do you believe God chose for you to experience the trauma you wrote about yesterday? Some people affirm that God chooses the pain they experience or the difficulties they have. I understand how that seems to make sense of things for them but for me it makes God something of a sadist. Maybe that's a bit strong but I think you know what I mean. Anyhow, do you think God chose the trauma you referred to so that you would become a hermit?]]

I have answered questions similar to this before, not about the trauma I referred to yesterday, but in general and perhaps in reference to the chronic illness/pain I deal with daily. You might look at, On Bearing the Crosses That Come Our Way. Other posts on the Theology of the Cross during the same time frame (@Aug. 2008) may also address this topic. My position on this has not changed but your questions take this position in a somewhat different direction than I may have taken in the past.

First, my foundational credo on suffering: I believe that God willed me and wills each of us to know God's love in whatever situation in which we find ourselves. I believe profoundly that God never abandons us --- even when others do. I believe that to whatever extent suffering is part of our lives because of the brokenness and distortion of our world (because most forms of suffering** are the result of the sin or estrangement from God which afflicts our world), our God will be there offering (his) comfort, encouragement, and empowerment --- even when we do not recognize the nature or the source of these things as we find ways to continue to live our lives and be our truest selves. I do not believe that God wills suffering, sends suffering, or somehow manipulates our lives and responses with suffering so that we might answer this vocation or that one. As I affirmed in the post linked above, God does not send us the crosses that come our way, but he does send us into a world full of them so that, through (his) grace, we may redeem them, and he certainly commissions us to carry those that come our way.

When I look at my own life I recognize that some of the pivotal circumstances of that life along with the life/love of God that dwelt and dwells at the core of my being together gradually created the heart of a hermit. But as I also noted, I could have lived that truth as a religious doing theology in the academy, working in a hospital chaplaincy program or in full time spiritual direction, as well as in a hermitage. I don't believe God created me to be a hermit, but I do believe God created me to be the fullest version of myself I could possibly be, that (he) continually worked to shape my heart, and when it began to look like a hermitage might be a place living my truth could happen, the shaping God had done helped me to perceive the promise of this way of life despite my own prejudices against it. (He) helped me listen to my heart, to the profound questions and yearning that resided there and to appreciate the way eremitical life might answer these beyond ordinary imagining. On the other hand, had I not discovered the possibilities or even the contemporary existence and meaningfulness of this vocation, I am certain God's shaping of my heart and movement within it would have empowered my recognizing and embracing another way to live the truth of who I am.

Whatever sense we make of suffering it is important that we do not truncate a theology of human freedom or a theology of Divine goodness and mercy in the process. I don't think your use of the term sadist is necessarily too strong in reference to a God who sends suffering or makes us suffer. Manipulative might be a better fit in some cases, but in either instance, the willing or sending of suffering is unworthy of the God of Jesus Christ who is Love-in-Act. Always God calls us to the fullness of human existence. What God ALWAYS wills is human life in abundance. When suffering comes our way God will accompany us and love us in a way which can prevent suffering from being ultimately destructive ("all things work for the good in those who love God," Romans 8:28), but this is far far different from sending or willing suffering.

I hope this is helpful.

** N.B., There are four forms of suffering that are "natural" or "existential"; that is, they belong to the human condition itself without reference to sin. Douglas John Hall outlines them in his book, God and Human Suffering. These are loneliness, anxiety, temptation, and limits. Loneliness underlies our hunger for love or the completion that comes to us in the other; it points to the dialogical nature of our very being. Anxiety is part of our need for security, peace, and the ultimate comfort of and communion with God. Temptation allows us to grow and mature in expressing our human dignity, to develop into persons of character, while limits are part of our drive for and achievement of transcendence; limits open us to surprise, to dreaming, to wonder and joy. There are also pathological and sinful versions of these forms of suffering but Hall is not speaking of these here.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

1:43 PM

![]()

![]()

Labels: suffering -existential forms, suffering- natural forms, sufferings of Christ

On Inner Work and the Importance of Having Healing Well in Hand Prior to Profession

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I wondered about the inner work you refer to having undertaken during the past 2+ years. . . . Does every hermit do this kind of thing? Did you need to do this because of difficulties you were having with your vocation? . . . I don't mean to pry but if a person needs to undertake this kind of work should their diocese profess them? . . . Please, I really don't mean to offend but you also write that candidates for profession to your life should have their healing pretty much in hand before profession. Do you still believe that?]]

[[Dear Sister Laurel, I wondered about the inner work you refer to having undertaken during the past 2+ years. . . . Does every hermit do this kind of thing? Did you need to do this because of difficulties you were having with your vocation? . . . I don't mean to pry but if a person needs to undertake this kind of work should their diocese profess them? . . . Please, I really don't mean to offend but you also write that candidates for profession to your life should have their healing pretty much in hand before profession. Do you still believe that?]]

Thanks for your questions. I understand where you are coming from and take no offense so please don't be concerned. First, I continue to believe that candidates for profession under canon 603 should have their own personal healing well in hand before approaching a diocese to petition for admission to profession and consecration. One must be relatively whole if one is to adequately discern or to commit to such a call --- perhaps even more than one needs to be in other more usual life contexts and commitments. Secondly, the inner work I have referred to over the past couple of years can be beneficial to anyone seeking to grow more fully into the persons they are called to be but who, over the years of their lives have been wounded in ways which may prevent a full, even exhaustive, response to God's call and presence. I don't know anyone who has not experienced some, even some very significant trauma or situations which wound personally and can prevent or at least hamper this kind of openness and response or "obedience." In fact, the inner work I have been referring to is geared to assisting every person to respond to God's presence and achieve an integrity of personhood which otherwise might remain merely potential.

At the same time I undertook this work when it became clear that there was significant essentially unhealed trauma I had grown up with and which needed to be addressed. I did so understanding that there was some risk this work might actually lead to the conclusion I was not really called by God to this vocation, but also, on the other hand, I appreciated that it was this very eremitical vocation that provided the time, motivation, and resources to do this work; more importantly, I think, it provided the personal, moral, and even the legal (canonical) obligation to do so as one publicly vowed to obedience and desiring to live the depth of the silence of solitude as well as "the privilege of love" identified as the core of Camaldolese life. Paradoxically then, I realized I was willing to risk discovering this was not my vocation precisely because I was in touch with the profound call of this vocation to personal wholeness and integrity. And over the past couple of years through this work I have only been confirmed in my conviction that it is in the silence of solitude that God calls me to an abundance of life I could not have imagined. So, while this work does not radically change my position on hermits having personal healing well in hand before petitioning for admission to profession and consecration it does nuance my position.

At the same time I undertook this work when it became clear that there was significant essentially unhealed trauma I had grown up with and which needed to be addressed. I did so understanding that there was some risk this work might actually lead to the conclusion I was not really called by God to this vocation, but also, on the other hand, I appreciated that it was this very eremitical vocation that provided the time, motivation, and resources to do this work; more importantly, I think, it provided the personal, moral, and even the legal (canonical) obligation to do so as one publicly vowed to obedience and desiring to live the depth of the silence of solitude as well as "the privilege of love" identified as the core of Camaldolese life. Paradoxically then, I realized I was willing to risk discovering this was not my vocation precisely because I was in touch with the profound call of this vocation to personal wholeness and integrity. And over the past couple of years through this work I have only been confirmed in my conviction that it is in the silence of solitude that God calls me to an abundance of life I could not have imagined. So, while this work does not radically change my position on hermits having personal healing well in hand before petitioning for admission to profession and consecration it does nuance my position.

One of the truths hermits sometimes recognize in rare cases is that they have been made ready for embracing a vocation to the silence of solitude for a very long time. This is not merely a matter of temperament but of formation by the combination of life circumstances and the grace of God. I came to see clearly that God accompanied me throughout my life, that (he) helped me understand and, in fact, be very sensitive to the difference between isolation and solitude from the time I was very small, that (he) gifted me in profound ways that actually suited me to a life of eremitical solitude as much as these gifts might have suited me to a life of apostolic activity in the academy or elsewhere. Tom Merton once wrote (perhaps tongue in cheek) that "hermits are made by difficult mothers"; Carl Jung once wrote that sometimes extraordinary and difficult circumstances can lead to a maturity which is surprising in someone who is so young. Analogously, extraordinary circumstances can suit one to eremitical life --- though it has to be emphasized these can also wound the person in ways which make her incapable of responding to such a call or even be unsuited to it. Since the externals of either case (i.e., life in solitude) can look similar or even identical it requires careful discernment --- and the assistance of those with experience in formation, etc., to determine the true character of the vocation with which one is dealing.

One of the truths hermits sometimes recognize in rare cases is that they have been made ready for embracing a vocation to the silence of solitude for a very long time. This is not merely a matter of temperament but of formation by the combination of life circumstances and the grace of God. I came to see clearly that God accompanied me throughout my life, that (he) helped me understand and, in fact, be very sensitive to the difference between isolation and solitude from the time I was very small, that (he) gifted me in profound ways that actually suited me to a life of eremitical solitude as much as these gifts might have suited me to a life of apostolic activity in the academy or elsewhere. Tom Merton once wrote (perhaps tongue in cheek) that "hermits are made by difficult mothers"; Carl Jung once wrote that sometimes extraordinary and difficult circumstances can lead to a maturity which is surprising in someone who is so young. Analogously, extraordinary circumstances can suit one to eremitical life --- though it has to be emphasized these can also wound the person in ways which make her incapable of responding to such a call or even be unsuited to it. Since the externals of either case (i.e., life in solitude) can look similar or even identical it requires careful discernment --- and the assistance of those with experience in formation, etc., to determine the true character of the vocation with which one is dealing.

The discernment needed in such cases is clearly significant, personally demanding --- and very rewarding. What absolutely must be evident to those involved in this process if they are to determine the hermit really is called by God to this vocation is that the person is genuinely embracing a call to human wholeness, has experienced the redemptive love of God in eremitical solitude in a significant way, and are compelled by personal integrity and faith to follow the work to its conclusion. I have noted this before here, but now I can be clear about the source of my conviction. With eremitical life specifically, coming to human wholeness involves a call to do this in "the silence of solitude". If one cannot do this or if one's growing wholeness and holiness makes one less able to remain peacefully in their hermitage, then one may need to leave eremitical life. If, however, this environment of eremitical solitude is clearly redemptive and the healing or sanctification one experiences as a hermit lead even more profoundly into the life of the hermitage, one's vocation will be confirmed.

But what if one is not (or is no longer) called to eremitical life? I believe that if one is not suited to eremitical solitude, living in this way will not have the same salvific character. Further, one may be unlikely to see the work required for healing to be a matter one must personally embrace because it is morally required by this vocation and one may therefore eschew it. In such cases, one will also have to submerge or even deny parts of themselves which are absolutely essential for personal wholeness and a life of responsive or obedient love.

But what if one is not (or is no longer) called to eremitical life? I believe that if one is not suited to eremitical solitude, living in this way will not have the same salvific character. Further, one may be unlikely to see the work required for healing to be a matter one must personally embrace because it is morally required by this vocation and one may therefore eschew it. In such cases, one will also have to submerge or even deny parts of themselves which are absolutely essential for personal wholeness and a life of responsive or obedient love.

More, as one undertakes the work required and experiences the healing it can effect in and of itself (that is, no matter the context), one is increasingly unlikely to be able to return to a physical solitude that may have been more mute isolation or escapism than what canon 603 describes as or allows to be called the silence of solitude. Eremitical life would simply not (or no longer) be healthy for one or what one could tolerate. Growing wholeness and fullness of life developing from the work undertaken will lead one to be increasingly unable to embrace the constraints of eremitical life. A more positive way of saying this is to note it will not represent the realm of freedom one really needs to be fully themselves, fully human. One will certainly not be able to truly know eremitism as a gift of God with which God gifts one either for one's own abundant life or for the sake of the Church and world.

Regarding your first questions, every responsible hermit works regularly with a spiritual director and beyond this, I have to trust that every publicly professed hermit will undertake the work or therapy or whatever it takes to fully respond to the vocation with which they have been entrusted once it becomes clear such work is called for. Certainly canonical hermits, hermits who have thus accepted the obligations and rights associated with eremitical life lived in the name of the Church, will generally be unable to eschew the necessary personal and inner work needed to embrace the life God summons them to within the hermitage or as someone with an ecclesial vocation. As I have noted before, I have been very fortunate in having a director who is specially trained in PRH and who was able to offer me the unique accompaniment needed to work through significant unhealed trauma even as she was able to keep her finger on the pulse of my vocation and assist in my ongoing formation. I do believe, however, that if one knows this kind of work is needed she should undertake it before admission to profession; it is entirely imprudent to forego it because of the effect healing has on the whole person.

While your question about this is a good and logical or understandable one, I was not having difficulties with my vocation. In truth, it was the fact that I was doing well in it which, at least in part, led me to realize the need for this work and gave me the courage to undertake it, risky though it might be to that same vocation. As hermits find in the silence of solitude, one must face oneself squarely in light of the love of God. A solitary life of prayer will uncover more and more any need for healing or forgiveness.

While your question about this is a good and logical or understandable one, I was not having difficulties with my vocation. In truth, it was the fact that I was doing well in it which, at least in part, led me to realize the need for this work and gave me the courage to undertake it, risky though it might be to that same vocation. As hermits find in the silence of solitude, one must face oneself squarely in light of the love of God. A solitary life of prayer will uncover more and more any need for healing or forgiveness.

As my director and I continue the work and deep healing God wills for me, and as I come to know and embrace my whole self even more completely in light of this work, I have experienced an even greater sense of eremitical call specifically as a diocesan hermit embedded in a parish community; with this my excitement regarding canon 603 and its implementation in the Church has grown significantly. I wish I had undertaken this work before profession (or at least known clearly it was still needed) as is prudent and ordinarily necessary, but I am grateful to God my very vocation made it possible as well as necessary that I undertake it now and that it in turn has led to the reaffirmation of an ecclesial call to the silence of solitude.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:53 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Canon 603, discernment of eremitical vocations, inner work, PRH, the Silence of Solitude

03 September 2018

On Birthdays and Anniversaries: Looking Back in order to Look Ahead

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

11:51 AM

![]()

![]()

02 September 2018

On Law as Unnecessarily Burdensome for the Hermit Life

Dear Sister, when hermits write about the law being a burden imposed on them by others and imposed in a way which prevents them from living eremitical life in simplicity and freedom what are they talking about? I am thinking about the following passages and others from the same post, [[People who augment laws and make them into millstones of detrimental outcome surely do so without realizing they themselves are causing the interference with spiritual progression and the freedom to follow Jesus in truth, beauty, and goodness.]] or [[The laws become so important to them, yet they increasingly are hindered by their own interpretation of laws in attempts to justify their positions and superiority they may claim as a result of the overly or misinterpreted laws. This can lead to their in essence interfering (or being tempted to interfere) with the simplicity and freedom that Jesus desires for others to follow Him in the truth, beauty, and goodness of the mystery of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.]] Does Canon 603 function in this way as a burden imposed without need and leading to a "detrimental outcome"? Do you think your own writing about the canon functions this way for some? Why would someone think this?]]

Dear Sister, when hermits write about the law being a burden imposed on them by others and imposed in a way which prevents them from living eremitical life in simplicity and freedom what are they talking about? I am thinking about the following passages and others from the same post, [[People who augment laws and make them into millstones of detrimental outcome surely do so without realizing they themselves are causing the interference with spiritual progression and the freedom to follow Jesus in truth, beauty, and goodness.]] or [[The laws become so important to them, yet they increasingly are hindered by their own interpretation of laws in attempts to justify their positions and superiority they may claim as a result of the overly or misinterpreted laws. This can lead to their in essence interfering (or being tempted to interfere) with the simplicity and freedom that Jesus desires for others to follow Him in the truth, beauty, and goodness of the mystery of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.]] Does Canon 603 function in this way as a burden imposed without need and leading to a "detrimental outcome"? Do you think your own writing about the canon functions this way for some? Why would someone think this?]]

Thanks for your questions. I couldn't locate the source of this citation to check out the context (not your fault of course!) but I wish I understood what is really being argued in such passages as the ones you quote. I can understand one source of your own questions. After all, the comments are so vague and overly general that it is simply difficult to understand whether they are cogent and for whom, in what way, or to what extent. Does every person interpreting or explaining a law or canon fall under this condemnation or is the person speaking of someone in particular? If someone's explanation of the law or canon means that some will discover they have misunderstood and misapplied either the law/canon or some of its central terms, does this mean the one doing the explaining has interfered with the others' freedom? If technical terms are explained in such a process so that some find they had a mistaken sense of what was really being said, is the one explaining the proper usage then guilty of interfering with the person's discipleship of Jesus? Since you say the person writing this is a hermit I can suppose s/he is speaking of c 603 and those who write about it, but unless s/he is speaking of somehow "making things difficult" for those already professed under this canon his/her comments make little sense. Here's why.

Thanks for your questions. I couldn't locate the source of this citation to check out the context (not your fault of course!) but I wish I understood what is really being argued in such passages as the ones you quote. I can understand one source of your own questions. After all, the comments are so vague and overly general that it is simply difficult to understand whether they are cogent and for whom, in what way, or to what extent. Does every person interpreting or explaining a law or canon fall under this condemnation or is the person speaking of someone in particular? If someone's explanation of the law or canon means that some will discover they have misunderstood and misapplied either the law/canon or some of its central terms, does this mean the one doing the explaining has interfered with the others' freedom? If technical terms are explained in such a process so that some find they had a mistaken sense of what was really being said, is the one explaining the proper usage then guilty of interfering with the person's discipleship of Jesus? Since you say the person writing this is a hermit I can suppose s/he is speaking of c 603 and those who write about it, but unless s/he is speaking of somehow "making things difficult" for those already professed under this canon his/her comments make little sense. Here's why.

Canon 603 applies in a legally and morally binding way only to those who have freely chosen and been chosen to be professed under it. It applies only when this person and her diocese have engaged in a serious process of mutual discernment and agreed to move forward with the profession and (in the case of perpetual vows) the consecration in the Bishop's hands under this canon. The canon is well-understood by all involved and canonists are available to explain the exigencies to both the hermit and her Bishop before any legal commitments are made. (They will also listen to the hermit who demonstrates on the basis of her own experience how terms in the canon should be nuanced and understood! The vocation is mutually discerned and in some ways, explored. The parties involved listen to one another to discern the will of God.)

NO SOLITARY HERMIT who did not experience canon 603 creating an extraordinary realm of freedom in which one can live the eremitical vocation or who felt that canon 603 functioned as a millstone preventing her from living her vocation in freedom and simplicity would ever seek or be admitted to such profession; moreover, if this situation was discovered after admission to first vows for instance, she would never seek or be allowed to be admitted to further profession or to consecration. If the Church changed the terms of the canon and a hermit found this burdensome in the way described, then such a hermit might need to pursue dispensation. Nor is this a problem since one does not need to be professed canonically to be a hermit within the Church. If one wishes to represent eremitical life in the name of the Church, if one wishes to serve the Church in this way and feels called by God to do so, then I wonder how the Church's own norm governing such a life could be considered unnecessarily burdensome.

As has been noted here a number of times canon 603 defines one particular eremitical vocation. There are other ways to live eremitical life so if canon 603 served to truly curtail one's freedom (not merely one's many liberties!) or seemed to complicate one's life in detrimental ways, it seems pretty clear that for such a person, this is not the avenue they should use to pursue living eremitical life. In other words they are not called to this specific vocation or to the specific rights and obligations associated with it and need not be troubled by the canon nor by those who comment on or interpret it. For that matter if the person commenting on or interpreting c 603 knows nothing about the canon or really seems to be speaking or writing in ways detrimental to the vocation itself and to hermits canonically professed under it, then again, why would anyone listen to them longer than it takes to check out their findings with other hermits and professional canonists who are recognized for being knowledgeable in regard to this canon?

As has been noted here a number of times canon 603 defines one particular eremitical vocation. There are other ways to live eremitical life so if canon 603 served to truly curtail one's freedom (not merely one's many liberties!) or seemed to complicate one's life in detrimental ways, it seems pretty clear that for such a person, this is not the avenue they should use to pursue living eremitical life. In other words they are not called to this specific vocation or to the specific rights and obligations associated with it and need not be troubled by the canon nor by those who comment on or interpret it. For that matter if the person commenting on or interpreting c 603 knows nothing about the canon or really seems to be speaking or writing in ways detrimental to the vocation itself and to hermits canonically professed under it, then again, why would anyone listen to them longer than it takes to check out their findings with other hermits and professional canonists who are recognized for being knowledgeable in regard to this canon?

I know that some have been upset to find 1) that they cannot live as a consecrated solitary hermit except under canon 603, or sometimes 2) that their dioceses refused them admission to profession under canon 603 (never an easy decision for the one being refused admission to profession!), or even 3) that their private vows do not initiate into the consecrated state but leaves them in the stable state of life they already found themselves in (whether lay or ordained). Others have been upset to find that c 603 was meant for solitary hermits (including those coming together for mutual support in a laura), and not for those seeking to form a community of "hermits" or as a way to be professed canonically so one can begin a religious institute. But in each of these cases those explaining these issues are merely explaining facts already known to the authors of the canon or the findings of expert commentators on the canon --- facts which need to be disseminated.

With different issues (e.g., what constitutes a laura, how does the silence of solitude differ from silence and solitude, what is the charism of the vocation, how important is spiritual direction or a diocesan delegate, what should formation look like and how long should it take, the place of temporary profession, the role of the Bishop, etc) we are dealing with elements of the canon where the lived experience of hermits can be especially helpful --- more helpful sometimes than the input of canonists, bishops, et al who have not lived the canon. To write about these is not to create law or to add onerous requirements; it is, in fact, to write about ways of ensuring the life is lived with integrity in true freedom when the canon itself is unclear or silent on the matter, or when time frames and other things which are applicable to life in community and established in canon law just don't work for solitary eremitical life.

Bishops, of course can take such comments and opinions for what they are worth. If they have a strong candidate for profession under canon 603 they are apt to listen to that candidate if something suggested really doesn't work for them. Still, if suggestions seem prudent to dioceses professing hermits under canon 603 dioceses have the right and even some responsibility to adopt these. Canon 603 is an ecclesial vocation so it is up to more than the individual desiring profession to determine what most seems to serve both the Church's eremitical tradition and her contemporary witness to the Gospel.

Bishops, of course can take such comments and opinions for what they are worth. If they have a strong candidate for profession under canon 603 they are apt to listen to that candidate if something suggested really doesn't work for them. Still, if suggestions seem prudent to dioceses professing hermits under canon 603 dioceses have the right and even some responsibility to adopt these. Canon 603 is an ecclesial vocation so it is up to more than the individual desiring profession to determine what most seems to serve both the Church's eremitical tradition and her contemporary witness to the Gospel.

You ask about my writing. I am sure my own writing has served as a source of irritation and disappointment to some --- most especially those who mistakenly believed (or persist in the argument) that private vows are the normal way to become a consecrated hermit, or who treat can 603 as an entirely optional way to solitary consecrated eremitical life. I'm pretty sure my writing has been a source of difficulty for those who are looking to use c 603 as a stopgap way to become consecrated as a lone person but not as a solitary hermit. But many more have found my writing helpful in explaining terms which those without a background in religious life might misunderstand and in addressing abuses that many have encountered over time. Fortunately, even more have found some of my posts on the spirituality and charism of canon 603 especially helpful. Because what I have written about canon 603 is rooted in my own experience, research, and education, and because I seek to convey truth which is not directly available to those standing outside this vocation, I don't believe it can serve as a burden unless one is not called to this same vocation but is instead seeking to misuse the canon as a stopgap for inappropriate motives. Other solitary (c.603) hermits will (and do!) mainly verify the essential truth of what I have written on the basis of their own experience.

As I have said a number of times here canon 603 is a truly beautiful balance of non-negotiable elements and personal flexibility which produces a sacred "space" where one can pursue solitary eremitical life with God in authentic and ever-deepening freedom. It is a timely canon which allows for a contemporary vocation our world and various cultures are truly hungry for --- without understanding what that actually is. Exploring it has been and continues to be a joy for me because it has served as I believe the canon is supposed to serve in the life of the solitary consecrated hermit, viz, it has deepened my understanding of the life, of its importance, of how God is using my life circumstances to witness to the Gospel and why that is significant for the Church and others. And of course it has served to structure and govern my life as it provides a stable context for focused growth as a solitary hermit in the Christian Tradition. This vocation is unquestionably a gift of the Holy Spirit and simply out of gratitude it deserves the best hermits', theologians', and canonists' experience, talents, and training or education can give it --- my own included.

As I have said a number of times here canon 603 is a truly beautiful balance of non-negotiable elements and personal flexibility which produces a sacred "space" where one can pursue solitary eremitical life with God in authentic and ever-deepening freedom. It is a timely canon which allows for a contemporary vocation our world and various cultures are truly hungry for --- without understanding what that actually is. Exploring it has been and continues to be a joy for me because it has served as I believe the canon is supposed to serve in the life of the solitary consecrated hermit, viz, it has deepened my understanding of the life, of its importance, of how God is using my life circumstances to witness to the Gospel and why that is significant for the Church and others. And of course it has served to structure and govern my life as it provides a stable context for focused growth as a solitary hermit in the Christian Tradition. This vocation is unquestionably a gift of the Holy Spirit and simply out of gratitude it deserves the best hermits', theologians', and canonists' experience, talents, and training or education can give it --- my own included.

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

5:32 AM

![]()

![]()

31 August 2018

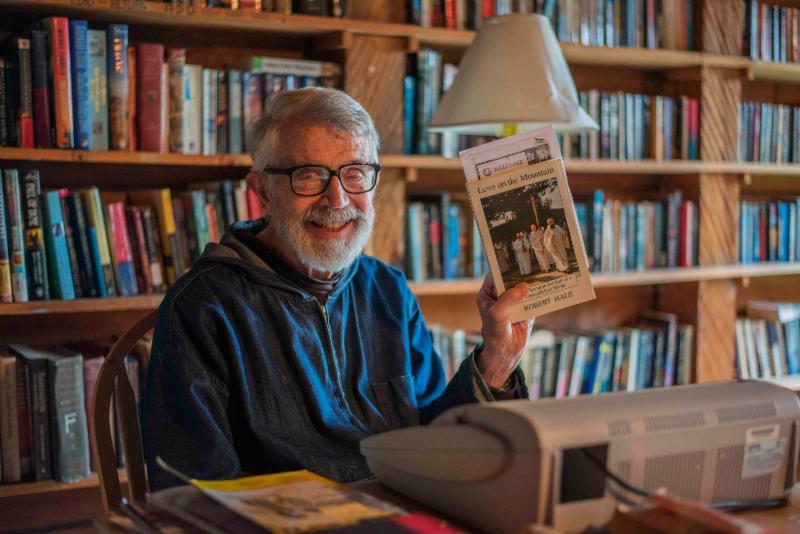

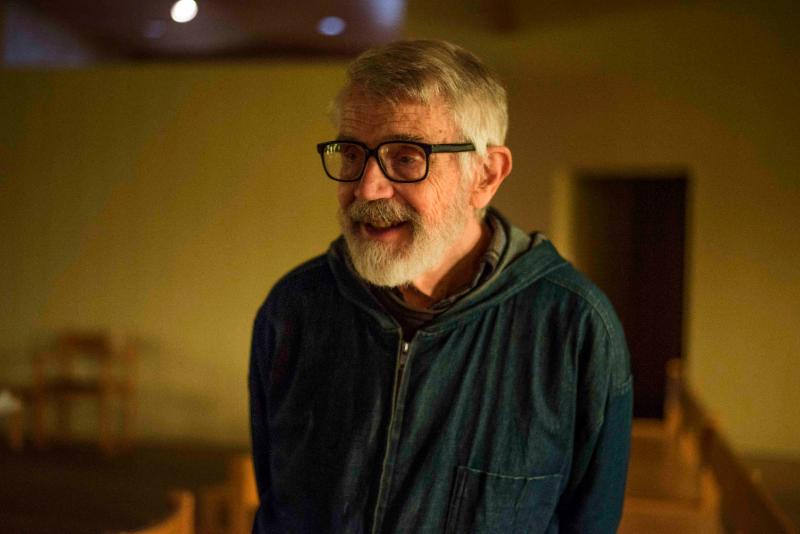

In Memoriam Dom Robert Hale, OSB CAM

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:50 AM

![]()

![]()

Labels: Dom Robert Hale -- In Memoriam

29 August 2018

Update On Father Robert Hale, OSB Cam

Update on Fr. Robert (Wed. 8/29):

Fr. Robert took a sharp turn for the worse Wednesday morning. He has been taken off of all life support now and transitioned into hospice/comfort care. It may be hours, it may be days, but we are certainly at the end of this phase of the journey. Fr. Andrew and I are with him. Please pray for the safe passing of our brother and father into the Privilege of Love.

Cyprian

Posted by

Sr. Laurel M. O'Neal, Er. Dio.

at

10:32 PM

![]()

![]()

Followup Question: Ancient and Contemporary Hermits, Ancient and Contemporary Asceticism

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

[[Dear Sister, in the history of hermit life isn't it true that hermits went out into the wilds without ways to support themselves and often had to live barebones, subsistence lives? Are hermits today not allowed to do this? I am asking because you have criticized the living arrangements of a lay hermit who seems to have taken on a project much like ancient hermits might have done and had no one to assist her. I think of some of these hermits as heroes and find their motivation completely inspiring, especially if they felt drawn into the desert by the Holy Spirit and were faithful to that call. So what is the difference between the situation you wrote about recently and these more ancient vocations? Isn't this kind of asceticism acceptable any longer?]]

Thanks for your questions and your very good points. First, let me say I generally agree with you about the ancient hermits you refer to. That is especially true if we are talking about folks like the Desert Mothers and Fathers from @ the 3rd-4th Centuries, the original Carthusians, the Camaldolese, etc. All of these hermits lived eremitical lives of serious asceticism and poverty. The deserts they entered required they make do with what they had at hand and that they live their faith commitments in and through such circumstances. Today the Carthusians continue to live similar lives --- though ordinarily in established Charterhouses with the basic means for healthy lives given to God alone. While people reading the stories of these hermits today might not understand what motivated or motivates them, I think most would find the accounts of their lives and foundations to be powerful witnesses to being driven by something greater than ordinary life seems to provide. One may not understand what moved these hermits but I think most would admire their courage and persistence.